Chris Hayes' ominous account of what's ailing America

In his new book, the MSNBC host frankly describes how a great many American citizens — disproportionately black and brown — live in a sort of internal colony

What is happening to America? Donald Trump has not even been president for two months yet and already the crises are hard to keep track of, from the fight over his Muslim ban to nearly constant diplomatic incidents created by his big flapping mouth, to his Cabinet stuffed with Wall Street goons.

How should we describe this? Enter A Colony in a Nation, a new book by MSNBC host Chris Hayes coming out later this month. He argues that for a fairly large segment of American society, the United States is not a democracy. Instead, a great many American citizens — disproportionately black and brown — live in a sort of internal colony. Their democratic rights are not respected: They have little or no access to due process, they are nearly helpless before predatory business, and they are alternately brutally repressed and mined for profit by a tyrannical state.

The Trump presidency is that colony's boundaries expanding. A decent number of previously enfranchised people are finding out what it's like to be on the business end of state repression, and they don't like it one bit.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Hayes' focus, in keeping with a book written before Trump was elected, is mostly on the the Black Lives Matter movement and associated protest actions, and the lived experience of people from the colony. He often uses examples from his own life for the latter category, which might seem a bit odd given his current job and fame. But he grew up firmly working class, the son of a community organizer, and lived in the Bronx in the early '90s when crime in New York was near its peak.

More importantly Hayes is honest. He frankly describes his dark thoughts and reactions to navigating a dangerous and racially fraught society without giving in to the histrionic self-flagellation that often characterizes such accounts. It all makes for an actually rather rare view into a wide racial and class cross-section of society: He spent a lot of time developing strategies to avoid getting jumped near his home and school, but also went to elite schools and spent time hobnobbing with the upper crust.

Naturally, Hayes gives the typical historical context as well, running through the whole sorry history of the erosion of black freedom in the post-civil rights era, from the war on crime and drugs to mass incarceration to stop-and-frisk. The riots in Ferguson, Baltimore, and elsewhere showed anyone with eyes that a great many Americans live under a tyranny — not just constantly harassed and brutalized (sometimes fatally) by cops, but coercively mined for cash to run the day-to-day operations of government, while most murders go unsolved. A democratic city is funded by taxes fairly levied by duly-elected representatives; a great fraction of Ferguson's government was funded by ginned-up tickets and fines on black residents.

Somewhat amusingly, Hayes explains the roots of the protests against police brutality by analogy to the American Revolution, one of the roots of which was nearly identical coercive extraction of taxes and fees to pay back British war debts. Unrest like that does not spring from nowhere; it grows in the seedbed of persecution.

This all might sound rather simple, and indeed the argument is perfectly straightforward. Yet it is still a necessary one. Hayes' experience with middle- and upper-class white people shows their repressive reaction is not completely irrational or unjustifiable. Crime, drug addiction, and the like are genuinely and rightly upsetting — and in minority communities most of all. Indeed, there was quite substantial support for tough-on-crime measures among many African-American communities during the great crime wave of the 20th century.

But the ruling classes did not temper these understandable reactions. Instead of modulating the thirst for vengeance with a recognition of the need for rehabilitation, they gave in completely to the lizard brain, making sentences savage and prisons hellish. They allowed due process to leak out of the vast majority of pre-trial detentions. They looked aside as police and prison cells became the dominant institution for whole communities. And instead of checking crime policy against diligent study about the roots of crime and the effectiveness of incarceration, they clung to comforting fables and knee-jerk bigotry — and didn't even consider that lead poisoning might have been the true culprit all along. As a result, as Hayes writes, the America criminal justice system now likely rivals the Soviet gulags in terms of the percentage of the population under supervision.

Liberals have been nearly as complicit in this as conservatives. Nixon may have started the war on crime and drugs, but some of the worst expansions of it happened under President Clinton and were pushed by Democrats. Hillary Clinton herself justified the incarceration of children back in 1996 with heavily racialized rhetoric about "superpredators."

And it's not only from 20 years ago. George W. Bush built a surveillance panopticon and a torture program; President Obama beefed up the spying and whitewashed the torture. President Trump has unleashed ICE raids throughout America, trying to root out unauthorized immigrants, and now even elderly white Australian children's book authors are being brutally harassed by border cops. But it was Obama who deported more people than any president in history, in an obviously moronic attempt to appease conservatives.

Every bad thing that Trump has done is rooted in some conservative tradition. At their best, liberals have checked and rolled back such abuses — as Martin Luther King, Jr. said, realizing that "their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom." But for decades now, they have not been properly minding the democratic store, alternately enabling and ignoring grotesque violations of constitutional rights. What we're seeing today is that such things tend not to stay in their proscribed confines. Hayes' book is an excellent view inside a disenfranchised sub-population, but it also serves as window into what's coming for everyone, if we cannot reclaim and rebuild our democratic system for everyone.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

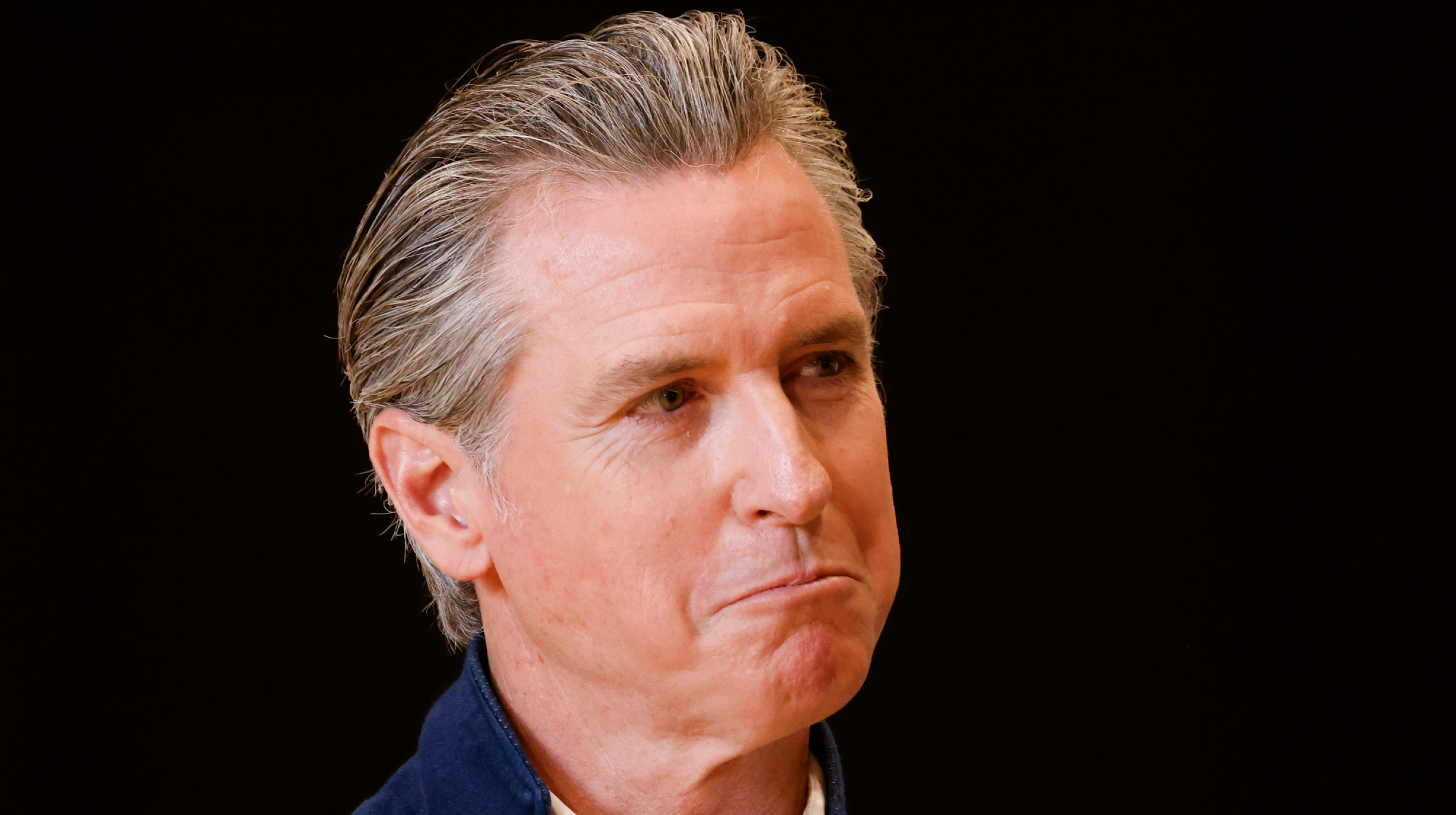

Gavin Newsom mulls California redistricting to counter Texas gerrymandering

Gavin Newsom mulls California redistricting to counter Texas gerrymanderingTALKING POINTS A controversial plan has become a major flashpoint among Democrats struggling for traction in the Trump era

-

6 perfect gifts for travel lovers

6 perfect gifts for travel loversThe Week Recommends The best trip is the one that lives on and on

-

How can you get the maximum Social Security retirement benefit?

How can you get the maximum Social Security retirement benefit?the explainer These steps can help boost the Social Security amount you receive

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?