How the filibuster became a cheap trick

It's time to fix it — or end it

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

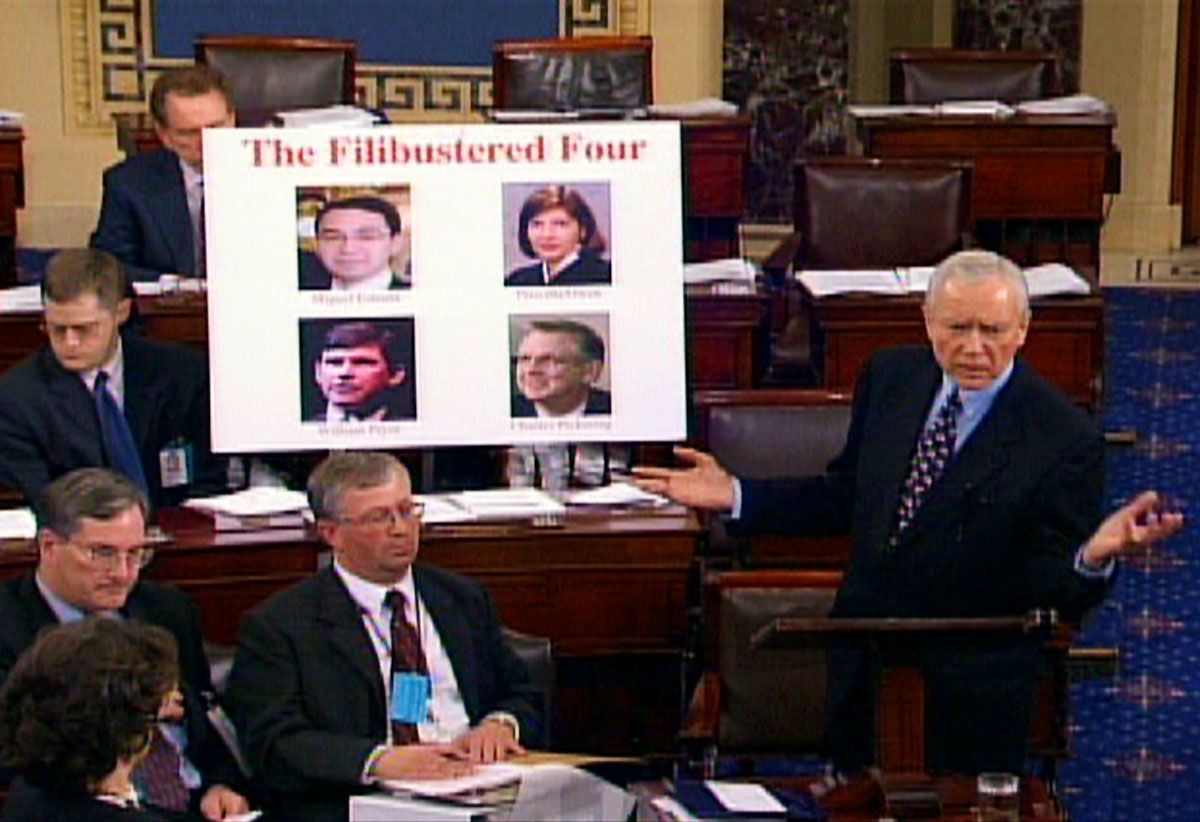

For the last 30 years, Republicans and Democrats in the U.S. Senate have played poker with judicial nominations, each side upping the ante round by round. Starting with the showdown over Judge Robert Bork's nomination to the Supreme Court in 1987, the confirmation process has become increasingly poisoned by partisanship. Later this week, the Senate will reach the final stage of the 30-year conflict — an end to filibusters on all presidential nominations via a rule change by the majority.

Republicans in the Senate have little choice if they want to confirm Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch. At least 41 Democrats have publicly committed to voting against cloture, a procedural step to limit debate and force a vote on the nomination. Back in 2013, then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) performed precisely the same maneuver to checkmate a refusal by then-minority Republicans to confirm seven nominations to the D.C. Circuit of Appeals. Reid changed the precedent to consider out of order any filibuster on all presidential appointees except those for the Supreme Court — a move that backfired on Senate Democrats when Donald Trump became president and they failed to win a majority in the upper chamber.

Now, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has an opportunity to finish Reid's work when the cloture motion will come up for a vote Thursday. Some members of his caucus worry that this escalation will eventually cause future Republican minorities in the Senate to have the same regrets as Democrats. More acutely, they also predict that this move will erode the basis for filibusters on legislation, chipping away what's left of minority rights in the upper chamber and rendering it functionally equivalent to the House of Representatives.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Is the legislative filibuster worth saving? Perhaps, but McConnell's action this week won't be what eroded it in the first place. That process began more than 100 years ago, and the real writing on the wall came 15 years before Bork became a transitive verb in the American political lexicon.

Traditionalists insist that the founders intended the Senate to be different from the House, and to serve as the more deliberative forum. That's true, but not through the filibuster, which did not begin until years after the ratification of the Constitution. Brookings Institute's Sarah Binder reminded the Senate in 2010 testimony that the filibuster was an accident of rules simplifications proposed by Aaron Burr in 1806. Until then, House and Senate rules were "nearly identical," and the first filibuster under the simplified rules didn't take place until 1837.

The Senate's original distinctiveness came from its separate mandate within the Constitution, which had House members elected through popular votes in districts to account for uneven population distribution in the states. In contrast, state governments appointed or elected senators to represent state interests equally. That ended in 1912, when the 17th Amendment forced all states to adopt popular voting for the election of senators, eliminating accountability to the states in favor of the same popular electorate as House members. That change, more than anything contemplated in the 105 years since, changed the nature of the Senate as a deliberative and separate entity.

Five years later, 80 years after the first filibuster, public outrage over Senate obstructionism during wartime forced the Senate to adopt a cloture rule that would allow a supermajority to end debate. Even so, filibusters were generally rare and not terribly successful, as they required continuous actual debate on the Senate floor. Filibusters didn't just block votes on a particular bill or nominee — they blocked all business in the upper chamber. After a series of filibusters on civil-rights legislation created a freeze in Washington, D.C., the Senate adopted a "two-track" system for debate in 1964, which allowed failed cloture votes on their own as stand-ins for filibusters and Senate business to otherwise proceed normally. Rather than having an average of one filibuster attempt in each Congressional session as it was in the previous decade, the average had grown to 17 per Congress by the mid-1980s — and then 52 in the final congressional session of the George W. Bush administration.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The filibuster became "the tyranny of the minority," U.S. News editor Robert Schlesinger wrote in 2010. "The filibuster is out of control. And it's dangerous."

That doesn't mean it's entirely valueless, however. Used judiciously, the filibuster has the power to rein in an extreme majority, and embarrass it by directing public attention to potential abuses. Now, however, the filibuster itself is the abuse. The shameful treatment of Neil Gorsuch and the personal attacks launched on a distinguished member of the appellate court for political purposes may be the nadir of this "tradition," even if it is the all-too-predictable result of the judiciary wars waged by both parties in the Senate and on the campaign trail.

If traditionalists fear the end of the filibuster on this week's so-called "nuclear option" vote, then they have a solution. Put an end to the two-track system and force senators into continuous debate to filibuster a bill or a nominee. Make a filibuster the end of all normal business in the Senate until the filibuster is resolved. The cheap nature of the modern filibuster invites abuse, and that leaves only two real options for a system based on majority governance — either get rid of it, or make it so costly that few will abuse it for long.

Either way, Senate Republicans should vote as a bloc to end the cheap use of a procedural ploy to obstruct Judge Gorsuch's confirmation to the Supreme Court. If that results in the end of the legislative filibuster too, they can either revert it back to its original form, or take comfort in the fact that it was an innovation in the first place — and one with a rather checkered history at that.

Edward Morrissey has been writing about politics since 2003 in his blog, Captain's Quarters, and now writes for HotAir.com. His columns have appeared in the Washington Post, the New York Post, The New York Sun, the Washington Times, and other newspapers. Morrissey has a daily Internet talk show on politics and culture at Hot Air. Since 2004, Morrissey has had a weekend talk radio show in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area and often fills in as a guest on Salem Radio Network's nationally-syndicated shows. He lives in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota with his wife, son and daughter-in-law, and his two granddaughters. Morrissey's new book, GOING RED, will be published by Crown Forum on April 5, 2016.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred