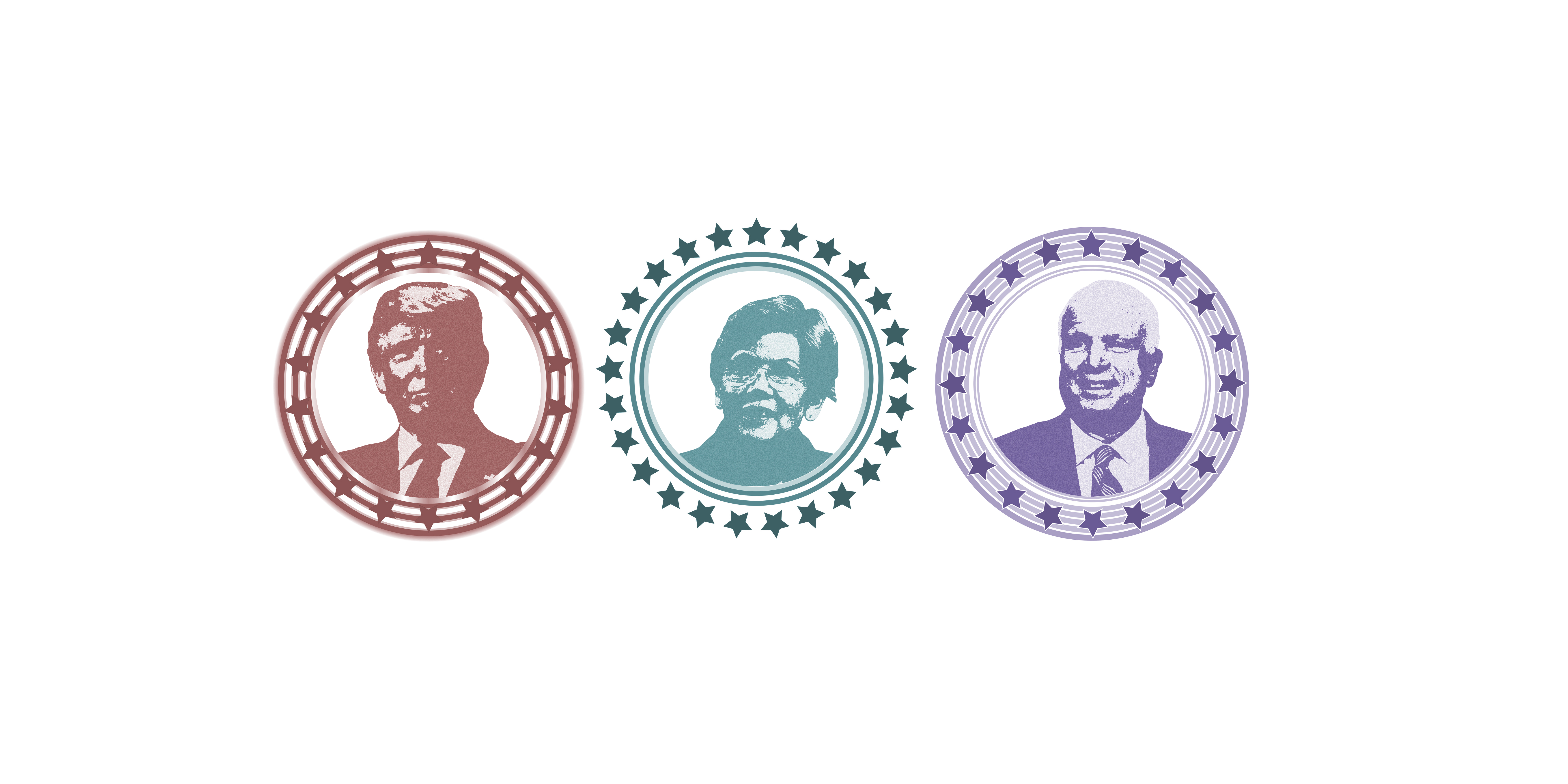

America now has 3 political parties. And the Republicans and Democrats aren't among them.

Forget the Republicans and Democrats. It's all about plutocratic populists, democratic socialists, and establishmentarian centrists.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Which of America's three political parties do you support?

I'm not talking about our major institutional parties — the Republicans and the Democrats, or lesser parties like the Libertarians or Greens. I mean the effective parties — the people, coalitions, and issues with which voters actually identify and around which they actually cluster when Election Day rolls around. Today, America has three such parties.

1. The plutocratic populists

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

On the right we have a party defined by President Trump's bizarre synthesis between plutocracy and populism. It supports deep tax cuts on the richest of the rich on top of the many earlier tax cuts from which this class has benefited since 1981. This party also wants millions of additional people to go without health insurance and aims to make drastic cuts in legal immigration. It hopes to break free from international obligations and the goal of spreading liberal democracy around the globe, to "deconstruct the administrative state" that imposes regulations on individuals and businesses, and to advance the policy preferences of the most conservative evangelical Protestants. The right-wing party's leading figures are President Trump, Attorney General Jeff Sessions, Kansas gubernatorial candidate Kris Kobach, and Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore.

2. The democratic socialists

On the left we have a party of democratic socialism. It supports a single-payer system of health-care delivery, free college tuition, and the breaking up of the biggest banks. It would impose draconian tax hikes for the wealthy, and probably tax increases for everyone else as well. It would substantially increase regulation, especially on the financial sector and on those industries that contribute to climate change. To the extent that this party has fully formed views of foreign policy, it supports sharp cuts to defense spending and a pulling back of America's military footprint across much of the globe. The left-wing party's leading figures are Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.).

3. The establishment centrists

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Finally, in the center we have a party of "neos": neoliberals and neoconservatives. This party supports free trade, relatively high rates of immigration, and American global leadership, including the use of force to spread democracy and punish those who defy that leadership. It favors a mixture of free markets and government regulation, with some factions leaning a little more or less in one direction or another. It is generally comfortable with tax rates that have prevailed since the Reagan Revolution. Its policy positions vary somewhat from election to election, but it usually opts for prudent incrementalism over bold new government programs or deep cuts. The centrist party's leading figures are Hillary Clinton, John McCain, Evan McMullin, Cory Booker, and a slew of mainstream media pundits (including Bill Kristol).

American Government 101 teaches us that whichever of our two institutional parties more successfully co-opts the center in a given election will prevail. In 2016, this (narrowly) happened in the popular vote, but it (even more narrowly) failed to happen where it counted — in the Electoral College. And so we ended up with the right-wing party in charge, which in turn provokes the left-wing party on a daily basis (and vice versa, echoing and reverberating throughout civil society).

When such a centrifugal cycle begins, it can be very difficult to break. (Study the breakdown of liberal democracy in Weimar Germany, Allende's Chile, or present-day Venezuela for examples.) The center gets hollowed out, caught in the crossfire between the extremes, attacked relentlessly and mercilessly from both sides. As a result, the return to equilibrium one might expect after the victory of a polarized alternative sometimes doesn't materialize.

But the reasons for this centrist failure go beyond abuse hurled from the extremes. The electoral success of those extremes in the first place is usually a product of real failures that the center fails to acknowledge and take responsibility for.

Take the stunning chart at the center of David Leonhardt's Tuesday column in The New York Times. It shows that after-tax income growth over the 34 years ending in 2014 has gone overwhelmingly to those at the tippy-top of the income pyramid. (A separate line on the chart shows that income growth in the 34 years leading up to 1980 was far more evenly distributed, and slightly favored those who earned the least.)

Despite overheated rhetoric about the extremism of each party's agenda during the 34 years between 1980 and 2014, this was a golden age for centrist government. Today's right-leaning centrists seek to emulate Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush, while left-leaning centrists follow the examples of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. Yet the shocking income stratification documented on that chart took place on all of their watches. Their policies made it possible; their policies would ensure it continues, or gets worse.

The same holds in foreign policy, where the center-right's victory in the Cold War nearly three decades ago has been followed by more than two decades of dithering and impotent do-goodism. The Iraq War was every bit the unmitigated disaster Donald Trump asserted it to be on the campaign trail. The war in Afghanistan has dragged on for an astonishing 16 years without a decisive victory. In Libya, the center-left Obama administration repeated nearly every error of Iraq in miniature. His would-be successor made it abundantly clear that her main criticism of the president under whom she served as secretary of state was that he was too reluctant to use force to overthrow yet another government in the Greater Middle East (Syria's).

Where is the soul-searching, the rethinking, the contrition from anyone in the "neo" center about this rather lame track record on both domestic and foreign policy? That would be a first step toward the center regaining the trust of the electorate. Without it, such trust will remain in short supply — and America's parties of the right and left will benefit from the vacuum in the middle of the spectrum.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred