The DOJ seized a New York Times' reporter's phone and email records. Here's why it matters.

The lessons of the DOJ's data seizure

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

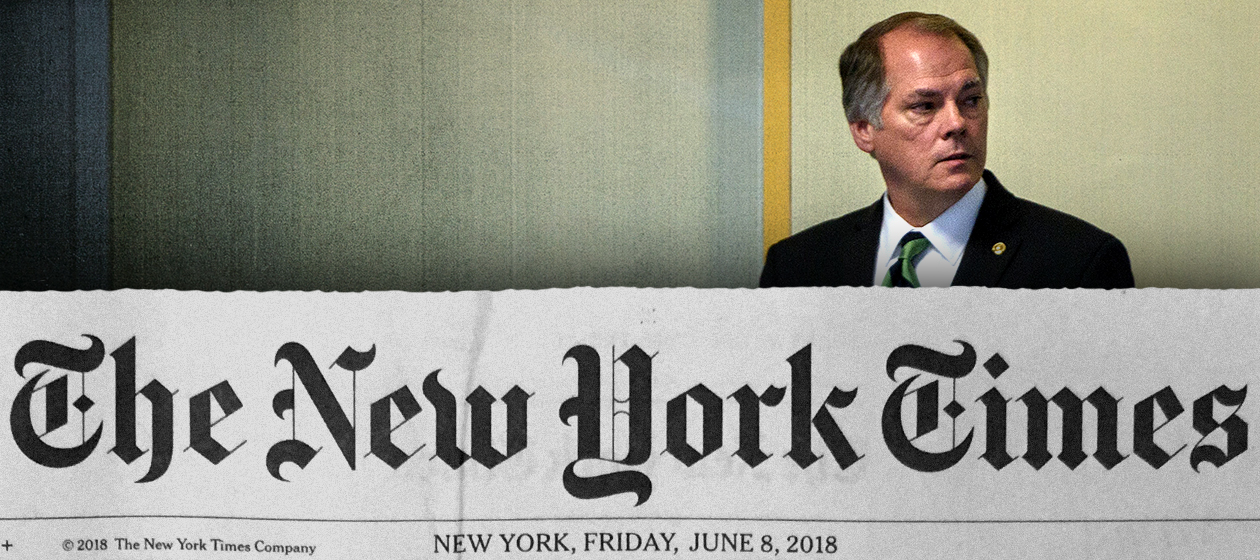

The arrest Thursday night of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence's former security director on charges of lying to investigators about his contact with reporters, and the revelation, pinned to the episode, that New York Times reporter Ali Watkins had her cell phone and email metadata obtained by the government in connection with a leak probe, may represent a one-off in terms of journalistic tradecraft. After all, Watkins knew the staffer, James Wolfe, quite well, and for several years. They were once in a romantic relationship.

Nonetheless, there are broader lessons to be learned. This is a big deal.

The Justice Department got Wolfe's cell phone records quite easily, and then asked him about his contacts with Watkins, who had reported several groundbreaking stories on the Russia investigation. Wolfe allegedly denied making the specific contacts.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

After (so says the Justice Department) availing itself of other means to try and establish the truth without obtaining the corresponding records of Wolfe's journalistic counterparty, they subpoenaed Watkins' personal cell and her Google account metadata. According to NBC News, matching the two sets of records showed that on the same day as Wolfe acknowledged receipt of a top secret document that contained details of a sensitive stream of intelligence about the investigation, he sent Watkins 82 messages. (The FBI did not obtain the content of those messages). Two weeks later, Watkins published a story that contained information that could only have come from that document.

The journalistic establishment will rightly protest the Justice Department's invasive efforts to obtain information about a reporter's source. This will chill speech in what is already a frigid environment for journalists. And the stakes couldn't be higher.

That said, journalists have a corresponding obligation to practice tradecraft that is commensurate with the gravity of the information that they're seeking. We must assume that the government will obtain the calling and messaging records of our sources, and so we need to find ways to obscure our contacts with them. Even sources who should know better — like (allegedly) Wolfe — need to be protected from their own instincts. Again, the stakes here are too high.

The obligation to aggressively hold the government accountable is paramount and never more so than when our institutions seem to be under attack from within, and when the rule of law is treated like a trifle. We cannot offer our strategic adversaries — the government — low-hanging fruit in the form of time/date coincidences. Sometimes, the risk-benefit analysis we make will permit us to take shortcuts. Maybe we should try and take the longer route.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I don't know anything about this story beyond what I read Thursday night. In late January, Watkins graciously spent time talking with members of my national security reporting class at the Annenberg School of Communications and Journalism at USC, and she stressed how critical it was to proactively protect sources. (She did not mention anything about being questioned by the FBI — and nor would I have expected her to). So it is possible that the bill of facts as laid out by the government are misleading. Watkins is an excellent reporter and I hope her work will not be undermined by snarky asides about her personal relationships. At the same time, her tale should cause everyone who cares about national security reporting to tread carefully.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.