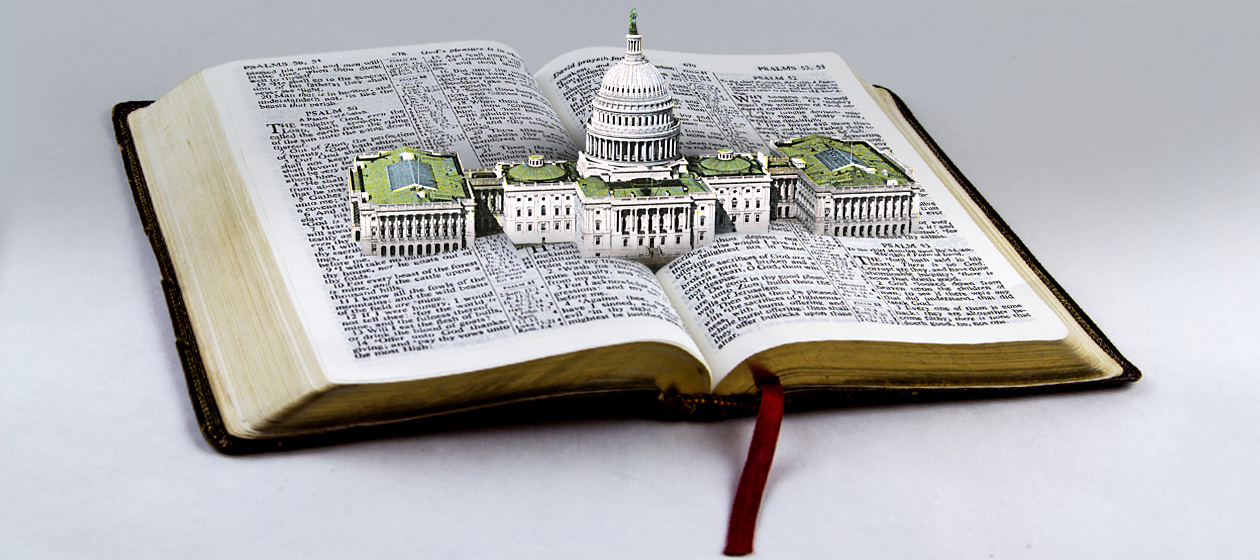

What the Bible really says about government

Was Jeff Sessions right to cite Biblical texts when justifying separating migrant families?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The internet exploded in fury recently when Attorney General Jeff Sessions quoted the Bible to defend his policies in separating migrant children from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border.

"I would cite you to the Apostle Paul and his clear and wise command in Romans 13, to obey the laws of the government because God has ordained them for the purpose of order," Sessions said, when defending President Trump's "zero tolerance" immigration policy. "Orderly and lawful processes are good in themselves. Consistent and fair application of the law is in itself a good and moral thing, and that protects the weak and protects the lawful."

The passage in question, chapter 13 of the Apostle Paul's Letter to the Romans, reads, in part: "Let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore whoever resists authority resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some people, mostly secularists unfamiliar with the Bible, took the passage to mean that Christians should just obey any government, no matter how awful. Other people, mainly Christians, argued that Sessions is full of it, because the Bible clearly preaches an open-door immigration policy.

They're both wrong. And it's important to understand why.

The Bible is a tricky text to interpret. Some people think this is because it's a grab bag of various texts from many centuries; you can make that argument, but there's no important text from human history that is straightforward to interpret, probably because otherwise, people wouldn't find them so interesting, and they wouldn't tell us interesting things about this messy reality we inhabit. The Bible is unclear, but so are Plato's dialogues, Shakespeare's plays, and the Constitution of the United States.

But there's another reason the Bible is so tricky to understand: While there are so many Christian splinter groups and eccentrics that you can always find someone somewhere who argued something or other, the broad tradition of mainstream Christian orthodoxy has held that Christian doctrine "works" by holding seemingly-contradictory beliefs together. Thus, the Bible at times seems to suggest that Jesus was a human being like anybody else, and at other times that he was divine; at times, it seems to suggest that there is only one God, and at others that there is God the Father, God the Son, and God the Spirit. Which is it? "Both," Christianity answers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And this is true when it comes to Romans 13, which is both a very complex and a very important piece of Biblical text. Some reacted to its seeming message ("Bow to the State!") with allergy. Thus we get headlines like "Sessions cites Bible passage used to defend slavery in defense of separating immigrant families," which is rather like those people who say you shouldn't listen to Richard Wagner because he was Hitler's favorite composer.

Like everything else in this world, Romans 13 makes sense within its broader context. And in the New Testament, this broader context is a big, raised middle finger at the government of the day, the Roman Empire. After all, Rome killed Jesus. And Paul is not short of contempt for the Roman Empire, which he likens to Old Testament-enemies of the Jews like Pharaoh and Babylon, and even at one points asserts that it is controlled by the Devil. So much for government worship.

So, what the heck? Well, Paul writes Romans 13 to say basically two things: First, just because the Roman Empire, and indeed most governments, are awful, doesn't mean that all government in principle is bad. And secondly, he wants to tell his audience that, while they should hold the Roman Empire in contempt and resist it however they can, they should not do so by breaking the law.

The first point, like Jesus' famous line about giving back to Caesar, is important, and not just because progressives who would like to strike it out because of its historic association with all sorts of government misdeeds should remember that it's also the justification for all the government programs they like. But because, even as it legitimizes government, it downgrades it. Again, you have to get the Roman Empire context: In Rome, government wasn't just absolute, it was literally divine. "Roma" was a goddess; all public offices were also religious offices; and executions for high crimes were sacrifices to the gods. So Romans 13 puts government back in its place: Yes, God wants there to be governments because otherwise we would have anarchy, but governments aren't divine. They're just institutions for raising taxes and maintaining public order.

The second point — to resist without breaking the law — is important, too, because it tells us that Paul was inventing something utterly unprecedented: peaceful resistance to an unjust government. Resist Rome, but be good citizens. The mode of interacting with public authority that Jesus first modeled, but that Paul and the other early leaders of the Church implemented, would be the blueprint for future successful nonviolent resistance movements, like Gandhi's and Martin Luther King Jr.'s.

So was Sessions justified in his little exegesis? Well, yes and no. In an important sense, yes, because Romans 13 means government in general is good, and it is impossible to have a functioning government without borders and enforcing those borders. This is important because too many Christians cite the Bible's many verses enjoining "kindness to the stranger" as if they were a Biblical warrant for an open-door policy. But they're not. What's more, Romans 13 also means that civil servants have a duty to faithfully apply the law, and as attorney general, Sessions' job description isn't to put into application what he thinks would be good policy, but what is actually on the books.

At the same time, Sessions was clearly disingenuous. Separating migrant families goes beyond just applying the law. More broadly, in practice, and by design, attorneys general have a lot of flexibility in how they apply the law, and Sessions clearly gets a kick out of applying it in a highly restrictionist way. After all, there is no formal law requiring children to be separated from their families. Also, Christians who don't want to apply laws they deem unjust do have an option: resign. To Trump's occasional chagrin, Sessions doesn't seem to have considered that. And everybody knows why: He's putting immigration restrictions in place not because he's a civil servant who puts his own wishes aside and dutifully follows the rules, but because he believes them to be greatly desirable. So if he wants to defend his actions based on the Bible, he should defend the merits of his actions, rather than hide behind Romans 13.

But this little skirmish might have served some purpose, by drawing attention to what the Bible says about immigration policy. America's immigration policy for more than 20 years has been to have one set of written laws and another set of unwritten ones, making a mockery of the rule of law and playing no small part in the delegitimization of the political process that has empowered demagogues like Trump. When Sessions, expounding on Romans 13, said that applying the law protects both the weak and the lawful, he might have been disingenuous with regard to his own actions, but he was certainly right in general. So, there's a lesson here for both sides: Just as conservatives need to wrestle with the plainly clear Biblical verses about sympathy to the stranger, progressives need to account for the clear Biblical verses about the necessity for sound government and rule of law.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.