How George H.W. Bush's successes actually set America up for failure

The greatness America found under Bush Senior was impossible to sustain

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

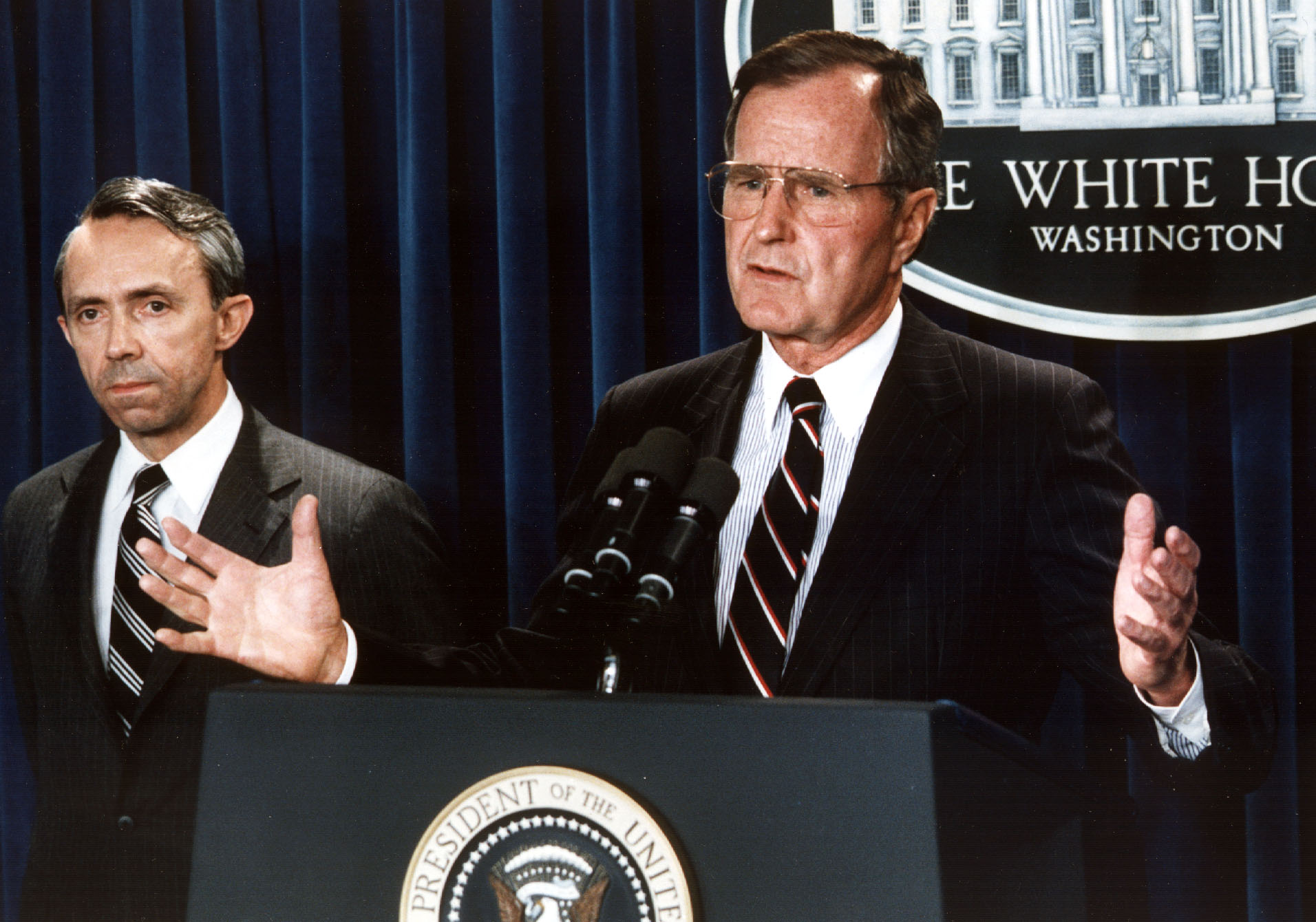

With the passing of former President George H.W. Bush, Americans have been treated to a series of encomia emphasizing the extraordinary gap in personal grace and style between the 41st president and the current occupant of the White House. The first President Bush believed in personal rectitude, in the value of diplomacy, in noblesse oblige. If only, we are asked to lament, America's elites, and its current government, believed in the same, then America would actually be great again.

In reaction, we've been treated to a different sort of eulogy, one that aims to remind America of everything they ought to dislike about the first President Bush, particularly those matters that prefigured the rise of Trump: the Willie Horton ad, the Clarence Thomas nomination hearings, the Iran-Contra scandal and the pardons that ended the investigation thereof. Either Bush was unwilling or unable to challenge the forces that would ultimately overwhelm his party, and transform it into an organization that would have no place in the future for a leader of his sort. Alternatively, perhaps those elements of style and character that seem so admirable are really just façades for class privilege, which would always be jettisoned when that privilege is threatened. Either way: Bush Senior was no hero.

But what is a hero? Both varieties of remembrance implicitly assume that this is the most important question: What was the character of the man, and how did that character make a difference in American history? But more than most presidencies, George H.W. Bush calls that mode of assessment into serious question, because the challenges that followed his tenure did so, to a substantial extent, as a consequence of success at facing the challenges directly before us at the time. It turns out that you can be a pretty decent character, for a politician anyway, and you can achieve considerable success — and still set your country up for a heartbreaking decline.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Consider Bush's record in foreign policy, widely considered to be his strong suit. His applications of military force, in Panama and, much more dramatically, in Iraq, achieved their stated objectives with speed and efficiency. His diplomatic successes were even more dramatic, successfully managing the peaceful collapse of America's leading rival, the Soviet Union. At the end of his tenure, America was widely and correctly perceived to be as strong, relatively and absolutely speaking, as it had been since the end of World War II. By any objective measure, that is a record of extraordinary success.

That record is not without its critics, nonetheless. His invasion of Panama set a bad precedent for American unilateralism that all of his successors have built upon to far more destructive ends. His slow-walking response to the breakup of Yugoslavia set the stage for the first attempted genocide on European soil since the Holocaust. His attempts to strong-arm Israel into making peace with the Palestinians through the Madrid process stuck America's nose into another country's business. His calm response to the massacre of protesters in Tiananmen Square missed an opportunity to stand up for American ideals and shape the future of a rising power. And in Iraq, Bush can be blamed for sending mixed signals that led to the invasion, then for sending American soldiers to fight to restore a corrupt monarchy, then for not finishing the job by ousting Saddam Hussein and supporting uprisings by the Kurds and Shiites.

But it should be obvious from a cursory examination of those criticisms that they contradict each other. If America should have sternly warned Hussein that the Iraqi-Kuwait border was sacrosanct, then we can't have been wrong to defend Kuwait when it was invaded. If America shouldn't have spent blood and treasure defending Kuwait, then we certainly shouldn't have pressed on to Baghdad, and taken responsibility for the reconstruction of Iraq. If you believe that, at the end of the Cold War, America should have eased away from leadership in Europe and let the Europeans manage their own affairs, as many critics of NATO expansion have alleged, then you can't plausibly criticize Bush for letting the Europeans take the lead in handling the crisis in Yugoslavia, which threatened no notable American interests.

Bush's foreign policy wasn't a consistently principled one. But it did pay consistent attention to America's interests as they were understood by America's leadership at the time. Even when it aimed at long-term transformation, as with support for German unification or for NAFTA, it was driven primarily by a sense of the opportunities present at a given moment in history rather than a grand conception of either history's end or of eternally unchangeable principles that stand outside history. Bush may not have been a hero, but he was a man for his time and place. And in its own terms, the fact that American power and influence around the world was dramatically enhanced over the course of his tenure should be the acid test for success.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But it is precisely that success which fuels the conviction that, had Bush made a different set of decisions, America would have achieved a more optimal result. The fact that American power was so great at the end of Bush's tenure is what makes so many critics believe that power must have been squandered, whether morally or practically, to bring us to the poor pass we're at in the world today.

President Bush's death is a good opportunity to question that assumption. Because what looks like squandering may be better understood as the inevitable consequence of success itself, and the ways that success sets one up for subsequent failure.

So perhaps America would be better off today if we had been more solicitous of Russian interests in the immediate post-Cold War period. But no leader after Bush was more solicitous than he was, and the reason those leaders were able to be less solicitous is that Bush had so successfully managed the dissolution of the Soviet Union that most of America's leadership wasn't really worried about Russia anymore. And perhaps America would have been better off backing away from the Middle East rather than attempting to manage its conflicts. But it was precisely the ease with which we brought the Gulf War to conclusion and restored the status-quo ante that encouraged Bush’s successors to think bigger, and for hubris to bring on nemesis. It wasn't our failure that created a predicament for America, but our success.

If we look back today at President Bush's New World Order and note that it didn't work out very well, it may be unfair to blame him, but it may also be unfair to blame his successors for not living up to the potential he realized or the example he set. Perhaps the problem was American dominance itself, and that Bush's very successes are what made us believe, foolishly, that it could be sustained.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred