Tucker Carlson has fired the first shot in conservatives' civil war over the free market

The right might finally be realizing there's nothing conservative about free markets

If anyone had suggested to me five years ago that the most incisive public critic of capitalism in the United States would be Tucker Carlson, I would have smiled blandly and mentioned an imaginary appointment I was late for. But that is exactly what the Fox News host revealed himself to be last week with an extraordinary monologue about the state of American conservative thinking. In 15 minutes he denounced the obsession with GDP, the tolerance of payday lending and other financial pathologies, the fetishization of technology, the guru-like worship of CEOs, and the indifference to the anxieties and pathologies of the poor and the vulnerable characteristic of both of our major political parties. It was a masterpiece of political rhetoric. He ended by calling upon the GOP to re-examine its attitude towards the free market.

Carlson's monologue is valuable because unlike so many progressive critics of our social and economic order he has gone beyond the question of the inequitable distribution of wealth to the more important one about the nature of late capitalist consumer culture and the inherently degrading effects it has had on our society. The GOP's blinkered inability to see beyond the specifications of the new iPhone or the latest video game or the infinite variety of streaming entertainment and Chinese plastic to the spiritual poverty of suicide and drug abuse is shared with the Democratic Socialists of America, whose vision of authentic human flourishing seems to be a boutique eco-friendly version of our present consumer society. This is lipstick on a pig.

Just as insightful as Carlson's monologue itself were the responses from various right-of-center commentators. J.D. Vance, the author of Hillbilly Elegy and a conservative who is known to hold somewhat heterodox views about the value of free markets, was given the space to praise Carlson in National Review. The movie critic Kyle Smith writing in the same publication called to mind what Auden said about "The romantic lie in the brain / Of the sensual man-in-the-street." Elsewhere Ben Shapiro raved about the cheap price of various products and pretended not to know the difference between the lifetime of good wages capable of supporting a family enjoyed by factory workers of my grandfather's generation and the fraught horror of hourly benefit-free employment at Nissan plants in the Deep South today.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But far and away the worst of the responses came from David French, alas, also in National Review. For French the chief problem with Carlson's argument was that it was grounded in something called "victim politics," which is post-Tea Party boomer code for "the feelings of people who are not as wealthy or as clever or as socially adept and culturally astute as I am." I wonder whether it occurs to French that "victim" could ever mean something other than a slur. What are mothers who sign away their minimum wage paychecks at 400 percent interest if not victims? And why should we excuse the grotesque behavior of their exploiters in the name of some windy nonsense about "freedom"? There is, one would think, a great deal of ideological space which reasonable persons might inhabit between Lin Biao and Ayn Rand, one where we can agree with the moralists of all ages and climes that, for example, usury is wicked.

It is difficult for me to understand exactly why conservatives have come around to their present uncritical attitude toward unbridled capitalism. It cannot be for electoral reasons. Survey after survey reveals that a vast majority of the American people hold views that would be described as socially conservative and economically moderate to progressive. A presidential candidate who spoke capably to both of these sets of concerns would be the greatest political force in three generations.

The answer is that for conservatives the market has become a cult. No book better explains the appeal of classical liberal economics than The Golden Bough, Sir James Frazer's history of magic. Frazer identified certain immutable principles that have governed magical thinking throughout the ages. Among these is the imitative principle according to which a favorable outcome is obtained by mimicry — the endless chants of entrepreneurship, vague nonsense about charter schools, calls for tax cuts for people who don't make enough money to benefit from them. There also is taboo, the primitive assumption that by not speaking the name of a thing, the thing itself will be thereby be exorcised. This is one reason that any attempt to criticize the current consensus is met with whingeing about "socialism." This catch-all talisman is meant to protect against everything from the Cultural Revolution to modest restrictions on overdraft fees imposed at the behest of consultants.

Whatever their public image might suggest, not all conservative commentators are pampered elites. If it were simply a matter of a privileged class attempting to secure its privileges by telling falsehoods, the ubiquitousness of market worship would be easier to understand — and to defeat. But the horrifying truth is many of them make arguments like "Payday lending is the best way to empower America's poorest people financially" because they somehow believe these things to be true.

This was not always the case. Attempting to discuss "conservatism" as if it were a concrete historical phenomenon or a ideology is a mug's game, but it is clear that on the whole those who might find themselves in sympathy with someone like Carlson today have been at best indifferent to and more often hostile towards commerce and the Anglo-American philosophical tradition of liberalism. L. Brent Bozell, the brother-in-law of William F. Buckley who helped to found National Review and served as Barry Goldwater's ghostwriter, came to reject all the tenets of fusionist conservatism because they appeared fundamentally at odds with all of those things he once believed they were meant to conserve. Russell Kirk, the author of The Conservative Mind, rejected the free market and indeed many elements of modern commercial and technological life, albeit in an occasionally affected and cloying manner. Christopher Lasch, the great cultural historian, was essentially a kind of Tory Marxist, a reactionary who agreed with the authors of The Communist Manifesto that capital would leave the "bonds and gestures" of civilization "pushed to one side / like an outdated combine harvester." Even Irving Kristol, the godfather of neoconservatism himself, could only summon up "two cheers" for capitalism and argued for the moral necessity of a broad and generous welfare state.

Going beyond the legacy of avowedly conservative thinkers, many opponents of capitalism, such as Theodor Arodno and Eric Hobsbawm, recognized the fundamental incompatibility of endless creative destruction not only with human dignity but with other more tangible things that intellectual conservatives claim to value, such as classical music and literature. In the so-called "global south," there is a thriving anti-capitalist discourse organized around the assumption that the Gates Foundation and the IMF — and not fundamentalist Islam — pose the greatest threat to the survival of traditional values. Conservatives should engage with these writers and thinkers — and going further back, with Keats and Beethoven and Dickens and Wagner and Heidegger, with all those who have valued what is fundamentally human for its own sake.

Fortunately there are already signs that the right-wing libertarian consensus is starting to come apart. In Why Liberalism Failed, a somewhat clunky book recently praised by Barack Obama of all people, Patrick Deneen argued that American conservatives are wrong to look to the Founding Fathers and to libertarian ideology for solutions to our present discontents. At American Affairs, the splendid magazine founded in 2016 by Julius Krein and Gladden Pappin, you can read conservative arguments for things like postal banking alongside articles by Marxist writers like Slavoj Zizek. Andrew Willard Jones, a talented young historian, has launched a new journal called Post-Liberal Thought to examine the question of how religious people can look beyond the political and philosophical legacy of liberalism. The conservative turn away from the market to the question of the human person and its innate metaphysical dignity has begun.

As with any revolution, there are certain obvious pitfalls to be avoided here. It is not a simply a question of turning back the clock — to 1966 or 1946 or some more remote date. A new political and social life founded upon the principle of solidarity, and not upon those of indulging our acquisitive instincts or congratulating our fellow achievers on having performed the rituals of competence, is one that will not be realized by role-playing characters from a preferred historical moment. Nor will it come about through modest reforms, however valuable some of these may be in the short term. Institutions will have to be altered — but so will hearts and minds. This is not an argument for quietism but for radical and difficult change.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

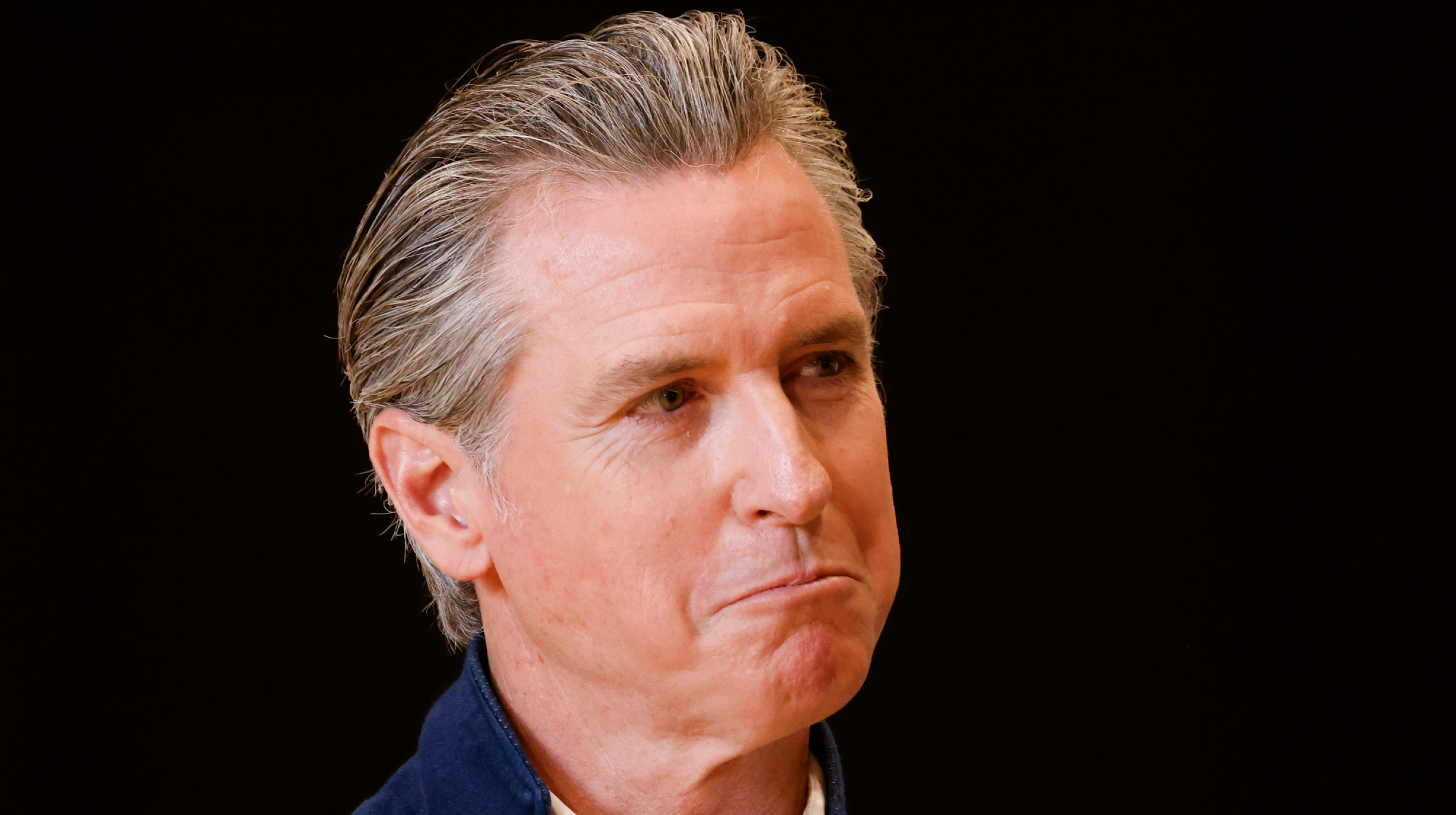

Gavin Newsom mulls California redistricting to counter Texas gerrymandering

Gavin Newsom mulls California redistricting to counter Texas gerrymanderingTALKING POINTS A controversial plan has become a major flashpoint among Democrats struggling for traction in the Trump era

-

6 perfect gifts for travel lovers

6 perfect gifts for travel loversThe Week Recommends The best trip is the one that lives on and on

-

How can you get the maximum Social Security retirement benefit?

How can you get the maximum Social Security retirement benefit?the explainer These steps can help boost the Social Security amount you receive

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?