How shutdown pain is spreading throughout the economy

It knows neither party nor geography

The causes of the ongoing government shutdown may be partisan. Its effects are certainly not.

Across red states and blue states, big cities and farmland, the weeks-long cutoff to the economic blood flow is making itself felt. And with Congressional Democrats and President Trump engaged in all-out political trench warfare over the president’s demand for a wall at the border, the shutdown — already the longest in U.S. history — shows no signs of ending anytime soon.

The most prominent and obvious damage done by the shutdown is to employment. Across the country, around 800,000 federal employees have either been furloughed or forced to keep working without compensation. Either way, they aren't getting paychecks, which means those paychecks aren't getting turned into purchases of goods and services in those workers' communities.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Washington, D.C., is feeling the brunt of the shutdown — out of every 10,000 workers in the area, 926 have had their paychecks cut off by the shutdown. That's the highest such number in the country, unsurprisingly. But other places where that number is high are less obvious. In Alaska, it's 173 workers for every 10,000, and in Montana it's 157. Washington, D.C., may be a Democratic bastion, but Alaska has two sitting Republican senators and Montana's two Senate seats are split. For Maryland, Wyoming, New Mexico, and South Dakota — a collection of states that's all over the map, politically speaking — the number is 100 or higher.

Appropriations bills were passed to cover 75 percent of discretionary spending before the shutdown commenced — hence reporters calling the shutdown a "partial" one. But that 25 percent hole swallowed large portions of several major agencies like the Department of Agriculture, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of the Interior, all of which maintain large workforces across the country.

Small towns outside of major national parks like Yosemite, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon all have large portions of their population employed by these agencies, for example. Park stores have shut down and paychecks have stopped coming in, and the influx of tourism — the parks are free now — hasn't been enough to make up for the fall in income to the permanent residents. "The big issue is the park employees and the word in town is [about] the effect on our local economy, with a high percentage of the community members not having their salaries for this long period," Tara Schiff, an economic development specialist for Mariposa County in California, told a local outlet. "The trickle down will be on our local market and possibly even the propane business and all the utilities that support the area."

The story is much the same in Huntsville, Alabama, where fully half the area depends — directly or indirectly — on employment from NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center, the Transportation Security Administration, and a number of other government projects. The local Redstone Federal Credit Union has already given out hundreds of low-interest loans and allowed customers to skip payments for a small fee, all to help local community members stay afloat. Now that the Federal Transit Administration has shuttered, cities throughout Arizona are having to fork over millions out of their own budgets to keep buses and other public transit up and running and to keep paying their workers. If the shutdown lasts through the end of January, money flows for a host of local transportation and construction projects could dry up. Similar struggles are going on in Colorado, Nevada, West Virginia, Utah, and more.

"The lunches that are missed and the shopping that is missed, people are staying at home, and that really hurts our small-business community," Tom Christopulos, the director of community and economic development for Ogden, Utah, told The Washington Post.

The shutdown also creates a more subtle problem: Even for a good deal of spending that was renewed, the checks still aren't going out because the federal workers whose job it is to process those payments have been furloughed.

Come the end of the month, government operations may no longer be able to pay their rent, sucking $460 million a month out of the economy and forcing landlords into the tough spot of going into debt lest they be unable to pay their own bills. Home loans aimed to support farmers in rural America, as well as payments intended to protect them from Trump's ongoing trade war, are all shutting off as the Agriculture Department furloughs its workers and can no longer process applications. On top of that, the agency also puts out supply and demand projections that help farmers decide how much of what crop to plant for the next season, and none of that information is coming out anymore either. "The cash flow situation in agriculture is really quite dire," Bruce Rohwer, an Iowa farmer, told NPR. "The ability to try to find ways in which to increase the cash that you are going to receive for your crop becomes ever more important."

Then there's all the economic activity, from new pharmaceuticals, to corporate IPOs, to automobile manufacturing, that all rely on federal approval and licensing processes that have either slowed way down or come to a complete halt.

Finally, there's the issue of straightforward government aid. Mandatory spending, which covers much of the federal welfare state, is not caught up in the shutdown. But programs like food stamps or home assistance either depend on an administrative structure that has been hit by the shutdown or on funds that sit in the murky divide between the mandatory and discretionary budgets.

Food stamps account for 10 percent of all U.S. household food spending, and housing assistance of some form or another covers 2.2 million low-income families. Federal housing assistance contracts with landlords began expiring as early as December. And while these programs have backup reserves they're dipping into, the money will not last past the end of February. Starting in March, food stamp assistance across the country could quite literally fall by 40 percent if the shutdown is still in effect.

It's true that, as a matter of raw GDP, the amount of money the shutdown removed from the economy was not that great. But like blood, GDP is a flow. The rest of the body economic needs the flow to keep coming to stay healthy. If the flow is cut off for any extended length of time, one part of the body begins to die. And if the rot is allowed to fester, it will spread.

As Sam Berger, a former Office of Management and Budget official in the Obama administration, put it to Bloomberg: "Shutdowns don't get bad linearly; they get bad exponentially."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

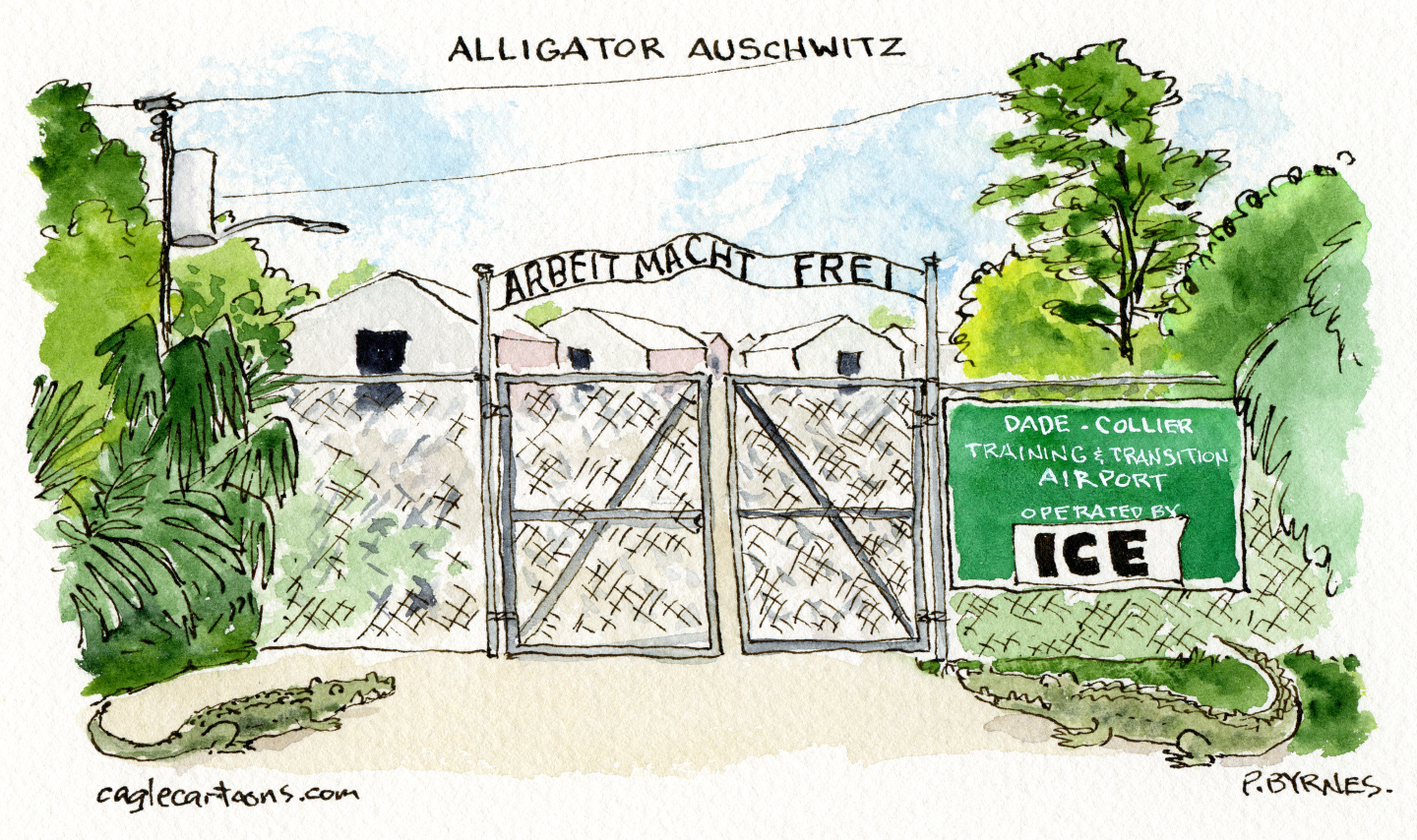

July 5 editorial cartoons

July 5 editorial cartoonsCartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an extrajudicial detainment camp, 'alligator Alcatraz', and tax cuts for billionaires.

-

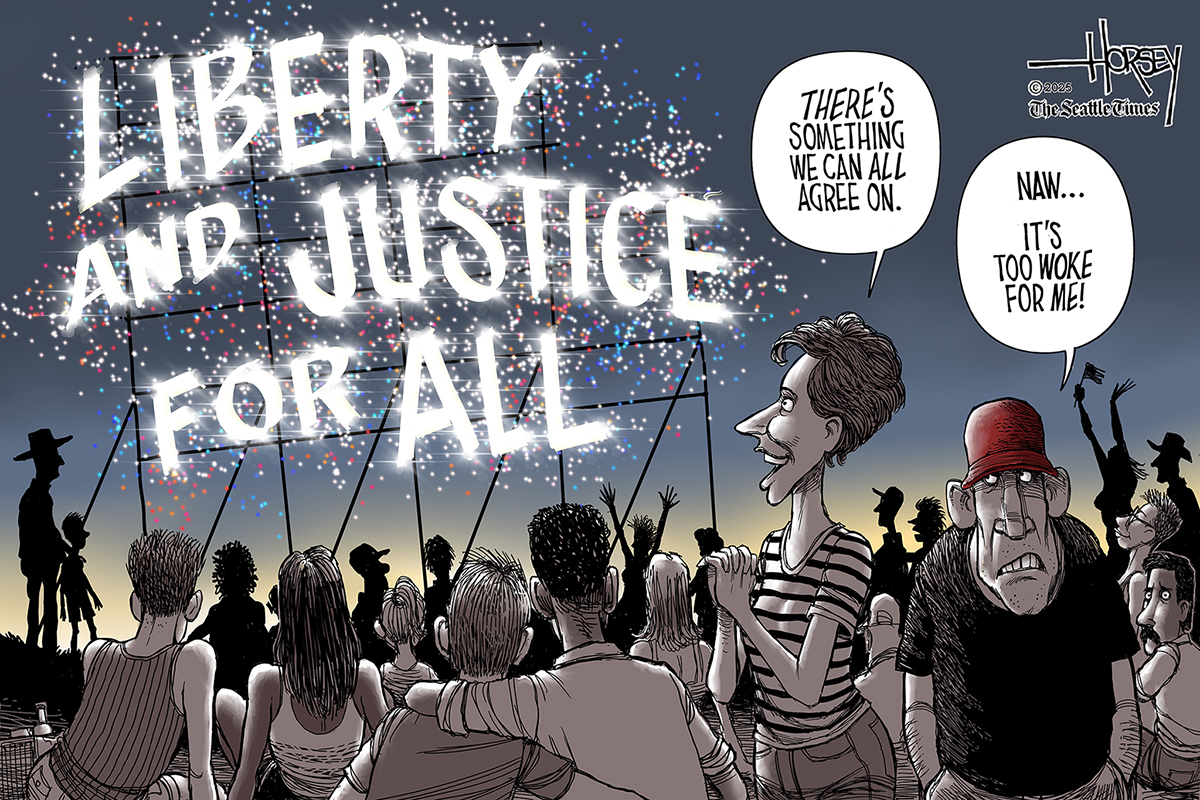

5 explosively funny cartoons about the 4th of July

5 explosively funny cartoons about the 4th of JulyCartoons Artists take on liberty and justice for all, a terrifying firework, and more

-

Jeff in Venice: a "triumph of tackiness"?

Jeff in Venice: a "triumph of tackiness"?In the Spotlight Locals protest as Bezos uses the city as a 'private amusement park' for his wedding celebrations

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?