If America can launch military strikes in Pakistan, why can't India?

On the perilous example set by the bin Laden raid

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As the most powerful country on the planet, America affects the world sometimes not by what it tells others to do but by what it actually does. Its actions establish norms that guide the behavior of other countries. Nowhere was this clearer than in India where Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched air strikes earlier this week to destroy terrorist camps in the heart of Pakistan — just like America did when it attacked Osama bin Laden's hideaway complex in 2011 and killed the 9/11 mastermind.

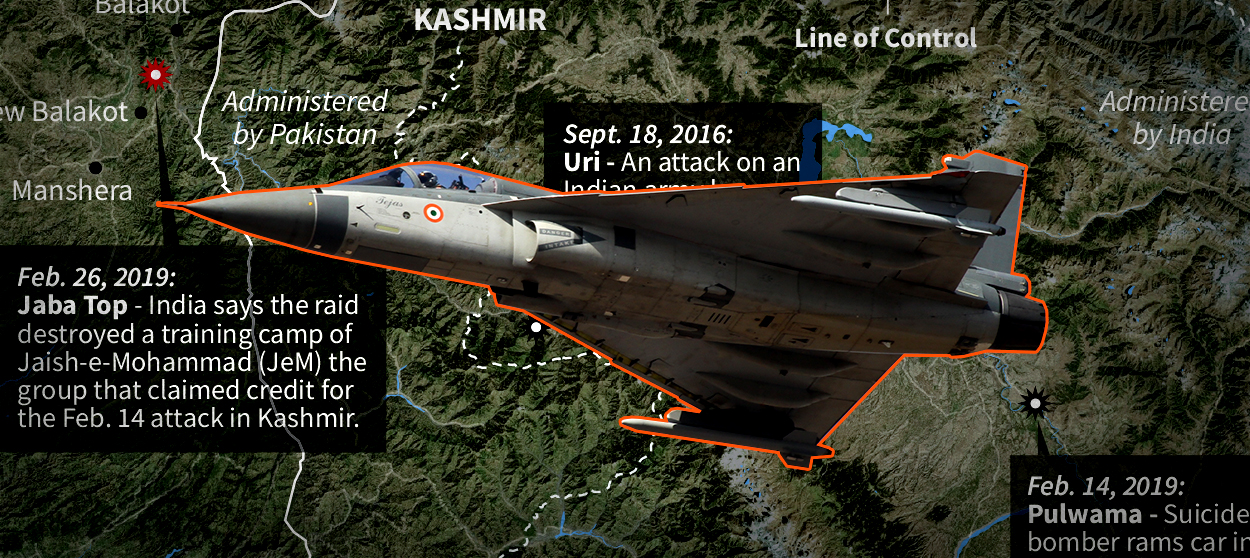

Modi's strikes were payback for a Valentine's Day suicide bombing in the northern Indian state of Kashmir where a terrorist linked to Jaish-e-Mohammed, a militant group headquartered in Pakistan, rammed 600 pounds of explosives into a military convoy, killing more than 40 Indian soldiers and wounding many others.

But India's response signals a new level of assertiveness that has less to do with effective counter-terrorism and more to do with appeasing street sentiment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The aid and comfort that Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence, a rogue agency whom the country's civilian government can't seem to control, provides to anti-India terrorist outfits had been a source of major tension between these two nuclear-armed neighbors long before Osama bin Laden masterminded his attacks on the World Trade Center. Jaish, and its sister terrorist organization, Lashkar-e-Taiba, both of whom oppose Indian rule in the predominantly Muslim Kashmir, have perpetrated several deadly attacks on Indian soil over 30 years.

The most spectacular was the Mumbai attack in 2008 when multiple Lashkar terrorists sailed into the city and conducted a series of 12 coordinated shootings and bombings including at a five-star hotel, synagogue, and train station over four days, killing 174 and wounding 300. But also audacious was the 2001 attack by Jaish on the Indian Parliament — when it was in session, no less — that killed six people. And then there was the 2016 attack in Uri, a town in Kashmir, where seven Jaish militants attacked an Indian army brigade, killing 17 army personnel.

This is by no means an exhaustive list. Indeed, Jaish alone has taken somewhere between 45,000-70,000 lives during its existence. The Indian government has repeatedly shared actionable intelligence with Pakistan about the culprits but, despite promises, Pakistani authorities have failed to take any meaningful action, partly because they can't get ISI to cooperate. Indeed, thanks to ISI's patronage, Jaish mastermind Masood Azhar lives openly in Bahawalpur where he runs a seminary and a media outfit. His nephew, meanwhile, heads a camp in Balakot, a city less than 40 miles from where bin Laden was ensconced in Abbottabad.

It is this camp that the Indian Air Force dispatched 12 Mirage planes to flatten with six 1,000 kg bombs, allegedly killing 300 terrorists. India dubbed this a pre-emptive, non-military strike — pre-emptive because it claimed to have intelligence that Jaish was planning more attacks and non-military because it studiously avoided Pakistan's military assets.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This might sound restrained but the fact of the matter is that it marks a significant escalation — even a "watershed" — compared to India's past reaction, notes Indian Express' Sushant Singh.

Indeed, after the Mumbai attack — whose scale and trauma were far greater than the recent one — the Indian government chose only to put diplomatic pressure on Pakistan. Meanwhile, although India mobilized its armed forces after the attack on the Parliament, its main focus was on rounding up the local colluders and putting them on trial. The only other time that India resorted to airpower was during the 1999 Kargil conflict when Pakistani soldiers disguised as militants crossed the Line of Control demarcating the border between the two countries and attacked the Indian army positioned there. But even then, India, despite its considerable conventional military superiority, didn't dispatch warplanes into the Pakistani hinterland and attack a civilian area. Its response now, therefore, represents a major departure from existing norms of engagement between the two sides.

Part of this no doubt is the result of the hawkish tendencies of Prime Minister Modi, who is up for re-election this summer. He has been a staunch advocate of a muscular foreign policy, boasting constantly about his ability — given his "56-inch chest" — to stand up to Pakistan. And, true to form, he amped the jingoism instantly after the recent attack, promising Indians that he would respond to Pakistan in a fashion that would make them proud.

But the fact of the matter is that even a more moderate leader than Modi would not have been able to ignore the desire of the Indian public to draw blood in the face of Pakistan's repeated provocations. Over 72 percent Indians now view Pakistan unfavorably — 64 percent of them very unfavorably — a 10-point increase over the last five years, according to Pew Research.

In light of this, the model of America's operation against Osama-bin-Laden — daring, precise, effective — was hard for Indian leaders to resist. Indeed, to do so given that America used it to such good effect against a similar adversary residing in the same country would have been an admission of impotence.

This is not mere speculation. Indian Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, not generally known as a fire-breathing nationalist, has explicitly invoked the parallel. He insists that, like the United States, India has the capacity to eliminate terrorist masterminds without taking major casualties on its own side. "This (a U.S.-style operation) used to be only a imagination, a wish, a frustration and disappointment," he maintains. "But it's possible today."

Pakistan has so far maintained its equanimity. In contrast to Prime Minister Modi's saber rattling, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan (a former cricket player who in his youth was a unifying heartthrob in both countries) has counseled calm and, in a show of maturity and goodwill, promised the early return of the Indian pilot captured from an attack plane that Pakistan downed.

However, it is unclear if Khan or his successors will be able to maintain such composure if India makes a habit of encroaching on Pakistani sovereignty to hunt down terrorists. And, yet, having now upped the ante, India is going to have a hard time dialing back its future response, all of which doesn't help reduce the odds of a nuclear confrontation.

Terrorism is a scourge and a bane. But the hard reality is that containment, for all its flaws, is the least bad option to deal with it. Military solutions, on the other hand, are generally the worst, not the least because they dull the desire for political solutions.

America got away with the bin Laden raid without immediate consequences because it isn't Pakistan's mortal enemy and doesn't have to share a neighborhood with it. And it has the resources, both monetary and geo-political, to buy its compliance.

But it may have set a terrible example for the two neighbors.

Shikha Dalmia is a visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University studying the rise of populist authoritarianism. She is a Bloomberg View contributor and a columnist at the Washington Examiner, and she also writes regularly for The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications. She considers herself to be a progressive libertarian and an agnostic with Buddhist longings and a Sufi soul.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff war

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff warSpeed Read The agreement will slash tariffs on most goods over the next decade

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire