The spread of lone-wolf terrorism is no accident

There are common messages behind many recent attacks, often echoed by the very loud voice in the White House

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

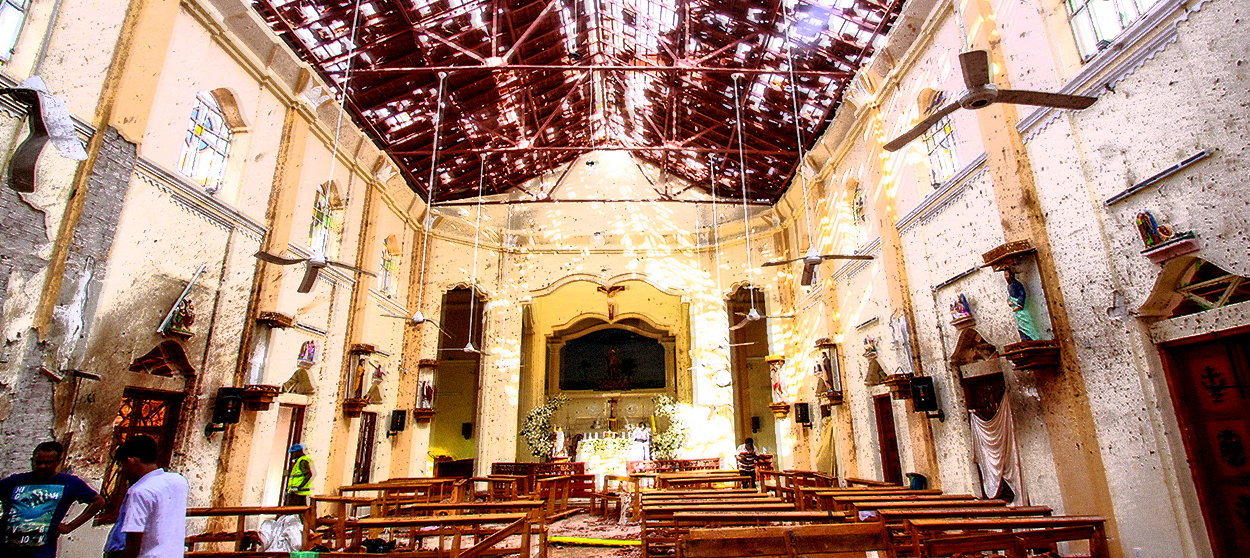

Are we trapped in a new cycle of grievance-inspired religious terrorism? Since the massacre of Muslim worshippers in New Zealand on March 15, there has been what seemed to be a massive revenge attack against Christians in Sri Lanka, a mass shooting at a California synagogue, and the arrest of an Army veteran, also in California, allegedly planning to avenge the Christchurch killings. It is a perilous moment, as religious worshippers all over the world attend services with an extra sense of fear and trepidation.

What is behind this recent epidemic of violence? While the Sri Lanka attacks appear to have been perpetrated by people with active ties to the Islamic State, many recent acts of terrorism have been carried out by individuals with no meaningful ties to organized extremism — so-called lone wolves. There's no single variable driving these attackers, but there's one piece of the puzzle that is increasingly undeniable: the president of the United States.

In the media, the concept of the "lone wolf" is haphazardly applied to everyone from the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing perpetrators to the 2017 Las Vegas shooter, generally to obscure sources of potential radicalization, and to bracket them as unknowable monsters. But scholars have attempted to craft a more specific definition. According to a 2010 article by scholar Ramon Spaaij, lone wolf terrorists are individuals (not small cells or even couples) who do not belong to extremist organizations and whose horrors are not directly orchestrated by any known group. But their acts fit the consensus understanding of terrorism itself — that is, it must be politically motivated violence directed against non-combatants. That part of the definition excludes Las Vegas shooter Stephen Paddock, who killed 58 and wounded 851 in 2017, but whose motive is unlikely ever to be known. Paddock, though, is the exception among recent examples.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

After white supremacist Anders Bering Breivik murdered 77 people in Norway in 2011, police found a bizarre, 1,518-page manifesto on his computer. Called 2083: A European Declaration of Independence, it was filled with rage against "political correctness," feminism and Islam, among other well-worn targets of both mainstream and fringe conservatism. Like many other white supremacist lone wolves, Breivik was a socially isolated loner, a single man who followed what Spaaij and fellow scholar Mark Hamm call "radicalization pathways." Breivik's life went off the rails, he found right-wing fascists and their "replacement theory" online and spent years training for and plotting his murderous escapade.

Lone wolves are usually motivated by the desire to commit what the terrorism literature calls "propaganda by deed." The goal is to draw attention to the cause, to inspire like-minded individuals to join in and build a mass movement. "Once you decide to strike, it is better to kill too many than not enough, or you risk reducing the desired ideological impact of the strike," Breivik said. Their isolation, and their tendency to spend time with fellow extremists online in forums like 8chan, fundamentally warps their expectations of what will happen in the aftermath of their obscene crimes. Surrounded by hate-filled peers, they repeatedly overestimate the willingness of others to do the same.

However, while their ambitions to spark a broad-based uprising are frustrated — because most people, thankfully, even those who sympathize with fringe ideologies, have no interest in mass killing — they can succeed in convincing a handful of future monsters to kill in their name. The Christchurch shooter mentioned Breivik specifically in his 74-page "manifesto." So did Christopher Hasson, the Coast Guard officer arrested (and later released in advance of his trial) plotting to carry out mass casualty terror attacks. The San Diego synagogue shooter cited both the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre and Christchurch. And on it goes. Mass murderers are devastatingly successful at drawing attention to themselves, and can be confident that any disjointed scribbling that they leave behind will be dutifully amplified by the media.

It is not an accident that ISIS-inspired lone wolf terrorism reached a crescendo in 2015-2016, when particularly grotesque attacks in France, the UK, Belgium, and the U.S. coincided with both the seemingly unstoppable expansion of the Raqqa, Syria-based ISIS "caliphate" as well as the attendant, cubicle-to-cubicle media hullabaloo. Each of these mass murderers received the Timothy McVeigh treatment, had their faces splashed across the pages of magazines and social media, creating a climate of fear and paranoia about Islam that only sharpened already-existing divisions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The territorial collapse of ISIS predictably reduced, although it did not exhaust, the supply of extremists willing to die to support the idea of a new caliphate. But as attention was focused almost exclusively on the threat of ISIS-inspired terror, far-right parties across Europe gained new strength in society and in parliaments, exploiting the threat of ISIS and fear of refugees to give new life to a racist, white identitarian vision of "The West." In the United States, Donald Trump rose to power threatening to ban all Muslims from entering the country and trafficking openly in anti-Semitic themes, a slapdash way of uniting anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish ideologues with a white nationalist undercurrent that usually stops just short of being visible.

The Trump White House might not quite be the Raqqa of global white nationalism. Trump, after all, does not call for racial or religious war and obviously has never cheered on gruesome violence against civilians as does the leadership of ISIS. But for the first time, the lonely, self-radicalized man can see an American president whose views and behavior are adjacent to violent extremism. President Trump has appeared on the racist conspiracy theorist Alex Jones' InfoWars program, issued press credentials to Islamophobic fabulists like the Gateway Pundit, and repeatedly retweeted extremists. His 2017 speech in Warsaw, Poland was filled with white nationalist dog whistles and his most important advisor today, Stephen Miller, is unquestionably a white nationalist. The president's rhetoric on immigration frequently bumps up against the boundaries of eliminationism. And the president consistently shrugs off concerns that right-wing extremism is a growing problem.

In New Zealand, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern delivered an impassioned and eloquent plea for peace in the aftermath of the shootings, arguing that "The world has been stuck in a vicious cycle of extremism breeding extremism and it must end." Her country immediately banned whole categories of assault weapons.

In the United States, on the other hand, Trump told reporters that he wasn't worried about it. "I think it's a small group of people that have very, very serious problems."

On some level, he is correct. The world does not seem to be on the verge of a large, white nationalist insurrection or a series of racialized civil wars. But neither President Trump nor his compatriots on the European far right — the Alternative For Germany, Marine Le Pen in France, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands — seem to understand that giving credence and legitimacy to white nationalist paranoia can create a context in which someone in that "small group of people" decides to make the leap from subreddit provocateur to real-life killer. President Trump's rhetoric is a radicalization pathway. And no one in his orbit seems willing to tell him so.

If President Trump were serious about the rise of far-right extremism and the cycle of retaliation and killing that will accompany it, he would say so. The president cannot eliminate the threat, but he could meaningfully reduce its salience —by publicly disavowing, by name, the extremist groups and individuals who admire and support him; by stripping press credentials from the Gateway Pundit; by assigning a staffer to make sure that no more racist extremists end up retweeted or praised; by giving a major address on tolerance after visiting a mosque; by stopping his constant demonization of undocumented immigrants; by redoubling the government's efforts to identify and combat right wing extremism rather than undermining them.

He will do none of those things, because President Trump fundamentally does not care, lacks the character or comportment to lead, and believes that he needs the support of far-right extremists to win re-election next year. The killing will go on, in stochastic fashion, until someone deems it politically expedient to try and stop it.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.