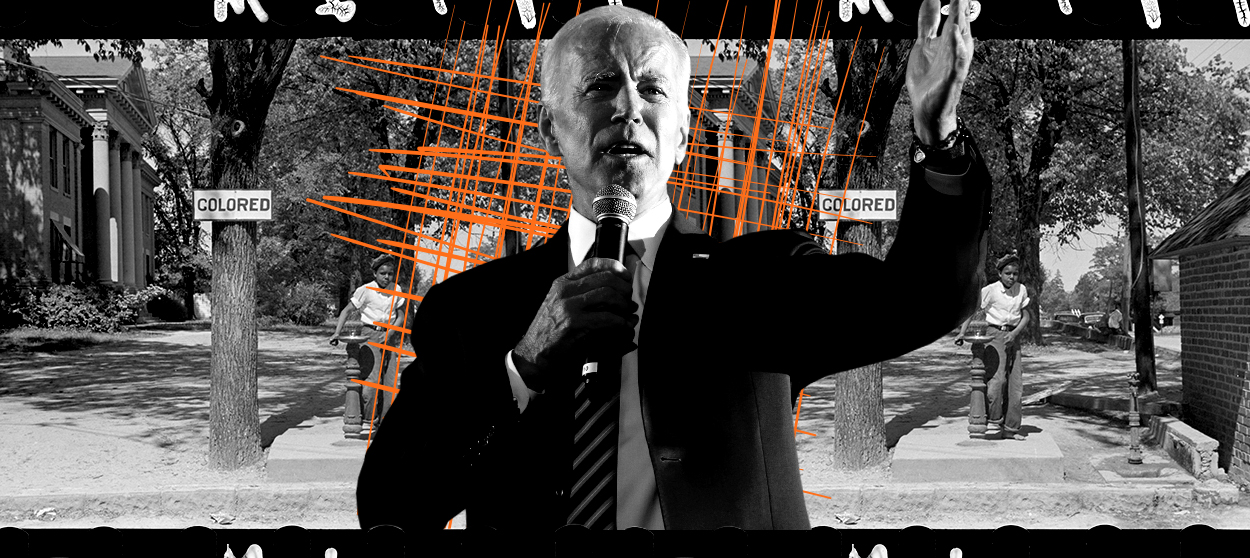

What Joe Biden apparently needs to learn about southern segregationists

Being able to be friends with Jim Crow Dixiecrats came at a terrible price

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Joe Biden is still leading in the polls for the Democratic nomination, and for unclear reasons he keeps bringing up dead racist guys who used to be his pals. At an event Tuesday night, he again brought up former Senator James Eastland, a Mississippi Dixiecrat and die-hard racist. "I was in a caucus with James O. Eastland," he said. "He never called me 'boy" … he always called me 'son.'"

The point, apparently, was that the parties need to get back to the good old times when politicians from South and North could disagree with each other but still work together. But this reveals a gruesome misunderstanding of the political context in which that sort of thing was possible — namely, a tacit agreement among whites of all sections that American blacks would be a subordinate caste.

For starters, Biden appears to have garbled the anecdote, because it makes no sense at all. A white southern aristocrat in those days would have never called another white man "boy," as that was a derogatory term indicating the place of black men in the Jim Crow status rankings. As Martin Luther King, Jr. once wrote about his own experience, under American apartheid, "your middle name becomes 'boy' (however old you are)[.]" And as Angus Johnston described on Twitter, Biden has told similar fond anecdotes about Eastland in the past, only recounting that he called Biden "son" instead of "senator." That makes a great deal more sense — though as Esther Wang notes, it's still indicating relative status within the white community, not just some term of endearment. A southern good old boy wouldn't call an equal "son."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But why could senators from Delaware and Mississippi be chums even if they "didn’t agree on much of anything," as Biden puts it? The reason is the great sectional reconciliation that happened in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After the South lost the Civil War, ex-Confederates attempted to preserve a racial caste system as close to slavery as possible, and brutally murdered hundreds of people — mostly blacks, but many whites as well — for supporting multi-racial democracy. Initially the North was infuriated at this attempt to reverse the outcome of the Civil War through terrorism, and Radical Republicans in Congress enforced universal manhood suffrage through a military occupation, aggressive police action, and three constitutional amendments. This was Reconstruction, the only period in the entire 19th century that the United States could be called anything close to a true democratic republic.

But northern whites (who were only slightly less racist than southern ones) gradually got tired of defending the civil liberties of their black fellow citizens. The Republican Party, founded specifically against slavery, became progressively more intolerant. In 1872 a faction of racist "liberal" Republicans — basically business conservatives in today's parlance — ran a third-party campaign against Ulysses S. Grant so they could end Reconstruction. That attempt failed, but after a huge financial crisis in 1873 created a depression the party was unable to fix due to its adherence to free-market dogma, they lost badly in the 1874 midterms. When the presidential election of 1876 ended in dispute, Republicans agreed to end Reconstruction in return for the presidency — effectively trading their most loyal voting block for a single term in office.

This was the beginning of sectional reconciliation. Southern whites used terrorism to destroy black liberties piece by piece, enacting brutal Jim Crow tyranny in law across the region. To disguise what was happening, a new popular understanding of recent history grew up. The Civil War was portrayed as a tragic misunderstanding, the antebellum South was painted as an idyllic, peaceful utopia, and the Confederate cause was said to be some vague notion of "states' rights" (instead of protecting an appalling slave empire).

Reconstruction was slandered as a period of rampant corruption and infringement of southern rights. Black Reconstruction politicians were smeared as inept and corrupt, and northern heroes like Thaddeus Stevens attacked as deranged hysterics. A sort of cult of personality grew up around many Confederate generals, with Robert E. Lee in particular seen as a sort of cross between Napoleon and Jesus Christ. Thousands of monuments to these vile traitors were put up across the country — in both North and South. Meanwhile, racist historians buttressed the case with tendentious books and articles.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As actual history, all this was and remains utterly preposterous (though it took many decades to undo this consensus, and many schoolchildren are still taught a version of the racist line to this day). However, the lies served an important political function. Reconstruction was hard. It took money, time, grueling effort, and substantial personal risk. As the memories of the war faded, and the war generation died out, northern whites instinctively looked for ways to shirk this labor, and be able to live in peace with southern whites once more. The route they chose was to sacrifice their African-American fellow citizens into the abyss of Jim Crow, and papered over what they were doing with a lot of comforting lies. As Josh Marshall writes, "what was gained … was gained at a terrible price and a price paid more or less solely by black citizens."

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s was a break with this comfortable fiction. It revealed the horrifying reality of Jim Crow tyranny, which Eastland (first elected to the Senate in 1941) defended for his entire career. Even among southern segregationists he was notorious as a violent racist and a rabid opponent of black rights. As Tim Dickenson notes in Rolling Stone, during the Montgomery bus boycott Eastland spoke before the White Citizens Council, where he said: "When in the course of human events it becomes necessary to abolish the Negro race, proper methods should be used. Among these are guns, bows and arrows, slingshots and knives… All whites are created equal with certain rights, among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of dead n***ers." He remained a Mississippi senator until 1978, which is where he became pals with a young Delaware senator named Joe Biden.

But Biden never grasped what sort of man Eastland really was. Like many whites of his generation, Biden appears not to have the slightest inkling of the history which allowed him to be buddy-buddy with despicable southern racists like Eastland and Strom Thurmond. That's despite the fact that he did not disagree with them on everything — on the contrary, he sought and received Eastland's support for amendments rolling back school integration, a classic example of the kind of bipartisan racism that propped up sectional reconciliation.

But that ship has sailed. Full-blown racism now grips the Republican Party (now the home of Eastland's political progeny), which is busily trying to disenfranchise as many black people as possible. Meanwhile, developments like the Black Lives Matter movement have led a growing number of Democratic voters to reckon with the historic racism that runs through every corner of American society. If Biden thinks he'll be able to restore bipartisan comity with a couple cigars and back slaps, he has another thing coming.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.