What the stories about the Amazon, Hong Kong, and Greenland have in common

Who owns a country and who are its people?

What do the fires in the Amazon, the Hong Kong protests, and the Trump administration's yen to buy Greenland have in common? In different ways, they're about two big political questions that sound much easier to answer than they really are: Who owns a country and who are its people?

Take the case of Greenland first. When Trump proposed buying the northern island, most of the world's reaction was "that's absurd" — buying territory is something that went out with the age of European imperialism. Nowadays, territory belongs, in some sense inalienably, to the people who live there, even when it isn't expressed in the form of complete independence.

Denmark's answer to Trump was, in substance, to point out precisely that: Greenland couldn't be sold because it belonged to the Greenlanders. But it's not obvious why that rules out buying the island; it just implies that America would have to pay the Greenlanders for it, rather than the Danes. (Or perhaps both, since the Danes do have security interests in Greenland.)

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So if the United States really wanted Greenland, would there be anything wrong with paying the inhabitants of Greenland an exorbitant price for their country? Would there be anything wrong with Greenland accepting? Why would buying Greenland be any different from admitting Estonia to the EU? From their reactions, it feels like many people believe it would be, but it's not clear from which political principle that belief arises.

Now take the case of Hong Kong. The people of Hong Kong are protesting because they fear they will be absorbed into mainland China's political system and that they will lose the freedoms they were promised would be retained under "one country, two systems." But why was Hong Kong given to China in the first place?

The answer is that Britain never "owned" Hong Kong — they leased it from the Chinese, and when the lease was up they had to return it. But what significance did that have for Hong Kong's people? They had been British subjects, and then they suddenly became citizens of the PRC, without being asked. To hedge against disaster, some Hong Kong Chinese emigrated, and others pursued second citizenships, second passports. But those were only options for individuals who could afford them, and in any event the community constituted by the Hong Kong Chinese did not get a chance to vote on its future. The people simply went with the land.

There was never a practical alternative to that outcome — the British were in no position to cross China on the matter, for one thing. But on the level of democratic theory it is unsatisfying, and we're seeing that dissatisfaction play out now in the protests. And yet the alternative to simply allowing Hong Kong to be extinguished would be to say that it itself had some degree of sovereignty — a solution that is not only politically impossible but could be downright dangerous in terms of the precedent it would set even if it were. Do we really want to say that any political unit that gets frustrated can simply go its own way?

Meanwhile, the Amazon is on fire, and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro is refusing international assistance in fighting those fires. Why? Because he is determined to take a stand on Brazil's absolute sovereignty over its territory. And it's far from a ludicrous stance. France may claim — correctly — that it has a national security interest in the Amazon because Brazil's forest is the world's lungs. But by the same token, Bangladesh may claim an even more compelling national security interest in the developed world's burning of fossil fuels, since climate change could well wipe their country off the map. They just have no power to defend that interest.

It cannot be that Brazil "owns" its forest until such time as other, more powerful countries declare that its choices are causing the world harm. That's not a workable conception of sovereignty. But by the same token, the profound interdependence of the global ecosystem is a fact, and a fact with deadly implications given the precarious state of the climate. And of course, if Greenland belongs to the Greenlanders, why shouldn't the Amazon truly belong to the indigenous populations of the forest? Who will speak for them? How different is Brasilia from Beijing?

In all of these cases, our extant political theory is of limited use. Governments derive their legitimacy from the consent of the governed — but who are the governed? The citizenry? Every segment of the citizenry with a distinct identity? Everyone materially impacted by the decisions of the government?

Finally, consider the immigration debate going on across the West. Restrictionists argue that the people of any country have an inherent right to choose who joins them, just like a co-op board has the right to let some people buy into a building, but refuse others. We may decide that some restrictions — like refusing someone because of their race or sexuality — are immoral, but that doesn't change our right to decide who comes into our country.

On the other side are advocates of a right to migrate. If people could migrate freely, then every country would be merely a legal jurisdiction — not materially different from a state within a larger national entity — and the members of the polity would be whoever happens to reside there at any given time. It's a defensible point of view in theory — but it's not clear why that right should be one-way. Why shouldn't legal entities be able to shift their boundaries as easily as people shift their residences? Where do the boundaries of that legal jurisdiction come from if not from the polity that created it in the first place? And if that is where it comes from, then why shouldn't it change as readily as the polity does?

Democratic theory presumes the existence of a self-conscious polity and a territory it inhabits, and then offers guidance for how to make government responsible to the true sovereign, the people. Nationalism, from a liberal perspective, involves such a community rising up to assert just that self-consciousness and to claim that sovereignty.

But our ideas about sovereign possession of land are older, dating from an era when the sovereign was an individual — a monarch — whose rights to rule territory (and the people living there) were not appreciably different from any property owner's rights to possess land. When these come into conflict, we don't actually have a good theory for how they should be adjudicated.

We could certainly use one.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

One year after mass protests, why are Kenyans taking to the streets again?

One year after mass protests, why are Kenyans taking to the streets again?today's big question More than 60 protesters died during demonstrations in 2024

-

What happens if tensions between India and Pakistan boil over?

What happens if tensions between India and Pakistan boil over?TODAY'S BIG QUESTION As the two nuclear-armed neighbors rattle their sabers in the wake of a terrorist attack on the contested Kashmir region, experts worry that the worst might be yet to come

-

Why Russia removed the Taliban's terrorist designation

Why Russia removed the Taliban's terrorist designationThe Explainer Russia had designated the Taliban as a terrorist group over 20 years ago

-

Inside the Israel-Turkey geopolitical dance across Syria

Inside the Israel-Turkey geopolitical dance across SyriaTHE EXPLAINER As Syria struggles in the wake of the Assad regime's collapse, its neighbors are carefully coordinating to avoid potential military confrontations

-

'Like a sound from hell': Serbia and sonic weapons

'Like a sound from hell': Serbia and sonic weaponsThe Explainer Half a million people sign petition alleging Serbian police used an illegal 'sound cannon' to disrupt anti-government protests

-

The arrest of the Philippines' former president leaves the country's drug war in disarray

The arrest of the Philippines' former president leaves the country's drug war in disarrayIn the Spotlight Rodrigo Duterte was arrested by the ICC earlier this month

-

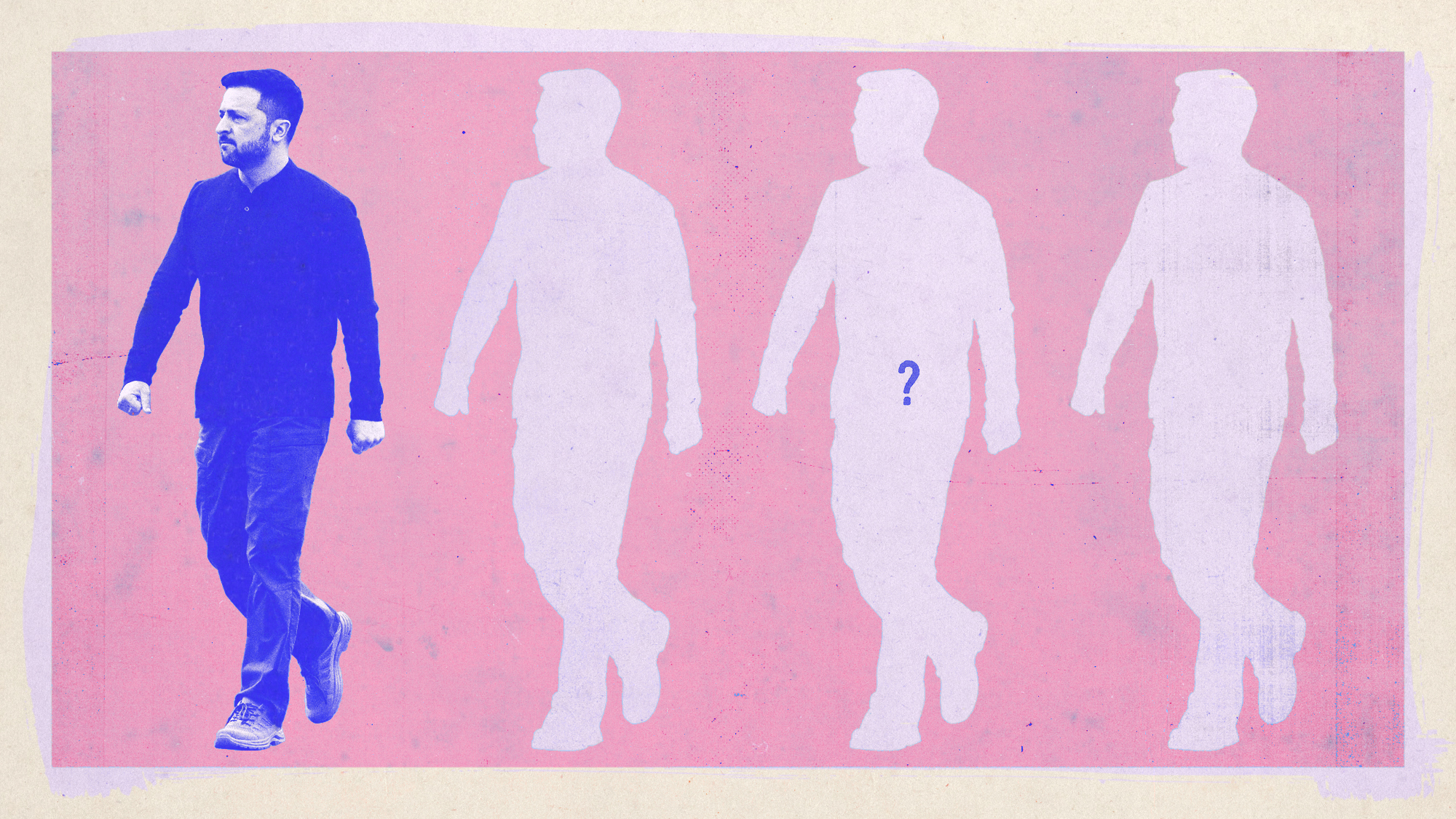

Ukrainian election: who could replace Zelenskyy?

Ukrainian election: who could replace Zelenskyy?The Explainer Donald Trump's 'dictator' jibe raises pressure on Ukraine to the polls while the country is under martial law

-

Why Serbian protesters set off smoke bombs in parliament

Why Serbian protesters set off smoke bombs in parliamentTHE EXPLAINER Ongoing anti-corruption protests erupted into full view this week as Serbian protesters threw the country's legislature into chaos