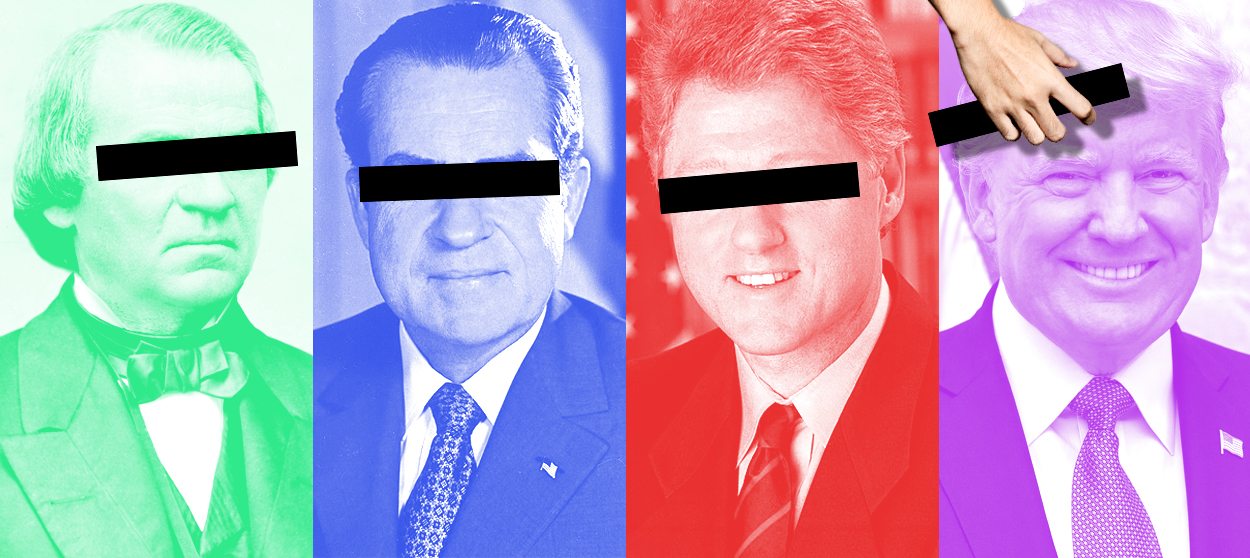

The enduring folly of presidential impeachments

Why will no one ever learn it doesn't work?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Like all 4-year-olds, my oldest is always changing her mind about things — which planet is the best, where to bury the treasure in the backyard, whether worms are yucky. Just yesterday she told me that her new favorite tape is Schoolhouse Rock. This is a welcome development. With apologies to Ariel and Sebastian, I would rather hear "I'm Just a Bill" 187 times a day than listen to "Kiss the Girl" even once more.

Why is there no "Impeachment Blues," I wonder? The way that it is discussed in American media these days one could be forgiven for having the impression that the impeachment of presidents — and Supreme Court justices — is an ordinary feature of American public life, comparable to, say, shifting control of the House. But it is nothing of the kind. Impeachment is a legal aberration.

It is also a process that has never succeeded. It is entirely possible that it was never meant to do so, that it appears in the text of 1789 for rhetorical reasons, as a kind of "Hic svnt dracones." It certainly never occurred to anyone before the end of the 20th century that it was the ordinary legal remedy for a president's political opponents. This is why articles like this one promising to explain "How the impeachment process works" strike me as ludicrous — it doesn't work and very likely never will.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Consider the first attempt at using the impeachment mechanism to remove an unpopular chief executive. When Andrew Johnson succeeded to the presidency, he had few allies in the executive branch. Only a few days after the surrender of Lee's army at Appomattox, the hero of the republic had been murdered and replaced by a Southerner. The conflict over the scope of Reconstruction that led to Johnson's impeachment would have taken place even if Lincoln had lived, but it is possible that rather than dismiss Edwin Stanton as secretary of war, Lincoln would simply have persuaded him to adopt a more conciliatory line. This is not what occurred. Despite Johnson's veto, Republican majorities in the House and Senate passed the Tenure of Office Act, which required the president to secure the approval of the Senate before dismissing a member of his Cabinet. A loophole gave Johnson the chance to suspend Stanton while Congress was out of session, which he did. What followed was a ludicrous series of events that culminated in the arrest of the interim secretary of war, poor Lorenzo Thomas; he would be released only when it became clear to congressional Republicans that the Tenure of Office Act might not survive the courts.

Instead, the House in 1868 voted 126 to 47 in favor of an impeachment resolution. Eleven articles of impeachment were then introduced. Most of these addressed Johnson's violation of the Tenure Act, but the 10th, for example, charged Johnson for his "attempt to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach, the Congress of the United States," which is to say, with making speeches in which he disagreed with his political opponents.

We all know how the story ends. The Senate voted on three of the articles, and in each case failed to secure a two-thirds majority that would have removed Johnson from office. He completed his term. The Tenure of Office Act was repealed less than a decade later, and since then it has been universally acknowledged that the firing of Cabinet officials — at any time, for any or no cause — is fully within the scope of presidential authority.

Though some of its incidental feature strike us as familiar — the conflation of innocuous behavior with apparent violations of clear federal statutes — on the whole the impeachment of Johnson bears little resemblance to those of either Richard Nixon or Bill Clinton. The background of the Civil War makes Johnson's case seem infinitely weightier than the proceedings against Nixon, who was re-elected in 1972 by a landslide. (If there is any lesson we can draw from his presidency it is that even a shrewd, non-ideological master of diplomacy willing to consider basic income and universal health care will be painted as a right-wing monster by American media.) His decision to resign without admitting wrongdoing rather than face the possibility of removal from office strikes me as the outcome most likely intended by the impeachment language in the Constitution.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Like Nixon, Clinton was ultimately caught in a procedural trap. But the difference between the two cases is that the Lewinsky affair was only the culmination of an endless series of cynical investigations meant to undermine his presidential authority. If shady real estate dealing was not going to bring Bubba down, lying about committing disordered sexual acts would — until, of course, it didn't. It is interesting, however, that, as with Nixon, whose domestic policies would be considered "socialist" by the standards of today's Republican Party, the tough-on-crime, anti-gay marriage reformer of welfare was so vehemently opposed by a party whose agenda he did so much to implement.

This, I think, is the real crisis in American public life, the not-all-that-gradual raising of stakes in what are ultimately partisan conflicts being fought very largely for their own sake. We saw it happening with George W. Bush in the heady days of Plamegate, a scandal whose significance I would defy anyone — especially those most closely involved in it — to explain in 2019. It happened again during the Obama administration, when the obvious reality that a disastrous war in Libya had turned into a personal tragedy for American diplomatic personnel became a sinister conspiracy. It has taken all but total control of our judiciary, which has metamorphosed almost overnight into a kind of Senate.

Long before his first day in office, Democrats decided that Donald Trump's presidency was illegitimate; virtually every appointment he has made to any Cabinet office or judicial position has been seized upon as a scandal; every remark or utterance he has made has been an admission of his complicity in some hitherto-unknown crime of devastating import. The domestic and foreign agendas of both parties have been suspended in favor of an all-consuming 24-hour, seven-day-a-week partisan war.

This process shows no signs of letting up. If the Democrats gain control of the White House in 2021 (unlikely) or 2025 (who knows?), what do they expect the seemingly invulnerable GOP Senate majority to do? Revert immediately to talking about infrastructure and bipartisan Band-Aid fixes to the Affordable Care Act? It is possible to imagine a Democratic president whose Cabinet appointments are held up for years, whose nominees for the Supreme Court are simply ignored as the number of justices shrinks to eight or even seven, whose pet legislation is never taken up in the Senate, and whose attempts to legislate unilaterally via executive order are widely decried as grotesque abuses of power and even ruled as such by Republican judicial appointees.

It is also all but inevitable that House Republicans will try to impeach President Tom Steyer for his tweets.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred