Will a wealth tax be crippled by avoidance schemes?

What both critics and supporters are getting wrong

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

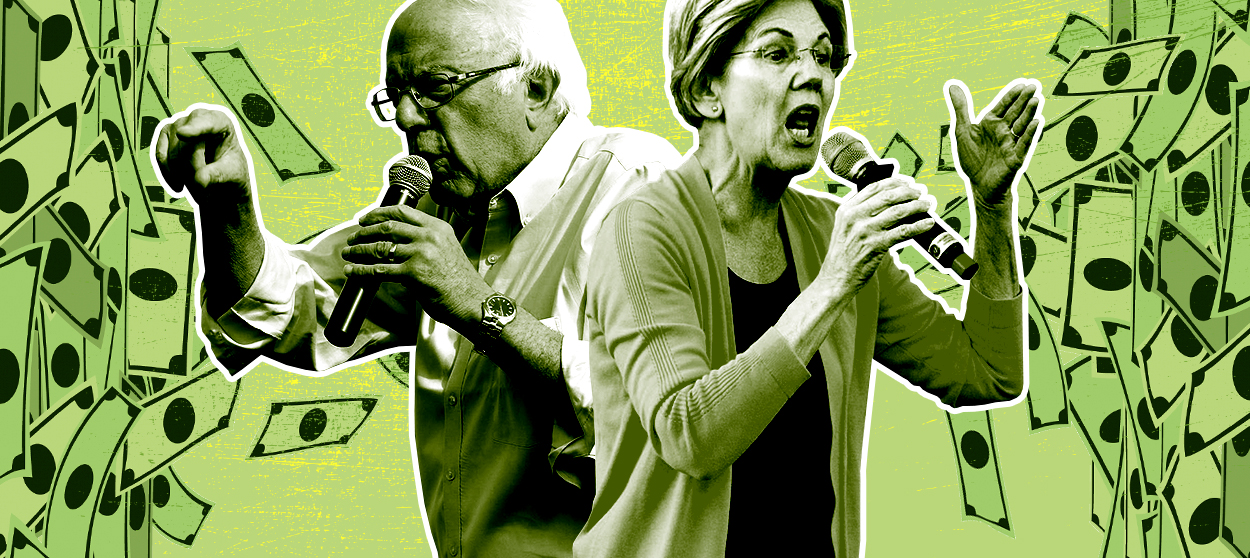

Wealth taxes are hot in American politics right now. Polling consistently finds that the idea of taxing the massive fortunes held by our richest citizens is broadly popular on a bipartisan basis. And the two most progressive candidates in the Democratic presidential primary — Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) — have dueling proposals to do just that.

But wealth is a mercurial thing, and more difficult to measure than straight income. Critics contend that a wealth tax would be crippled by avoidance schemes the rich would cook up. As an idea, a wealth tax may fire people up. But would it actually work?

I can't answer that question for you in a single column. But it's not just complicated because of the technicalities of tax evasion. It's hard for everyone to even agree on what a wealth tax "working" would mean.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One of the arguments worth engaging with comes from Larry Summers, who's worked in previous Democratic administrations, and his co-author, Natasha Sarin, who point to the already-existing estate tax, which itself is a form of wealth tax. And revenue for the estate tax chronically comes it at much lower levels than you'd expect if you just ran the raw numbers on the tax rate and the amount of wealth it could hit. Summers and Sarin argue this is due to numerous evasion strategies: "questionable appraisals; valuation discounts for illiquidity and lack of control; establishment of trusts that enable division of assets among family members with substantial founder control; planning devices that give some income to charity while keeping the remainder for the donor and her beneficiaries; tax-advantaged lending schemes" to cite a few examples.

As a crude intellectual exercise, they use the results of the estate tax to estimate Warren's wealth tax would only bring in one-eighth to three-eighths of the roughly $200 billion in annual revenue she calculates. They don't do this so much to claim their numbers are right, as to point out the enormous variances evasion can cause. (This same problem would also apply to Sanders' proposal, which is even more aggressive.)

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, the economists who consulted with Warren and ran her numbers, certainly aren't unaware of this criticism. They point out that the make-up of wealth among the very rich is different than among average citizens: 80 percent of the wealth held by the top 0.1 percent is in stocks, bonds and real estate, which are actually pretty easy to measure and value. Warren has committed to keeping the definitions and language of her tax bill as clean and simple as possible, so as to avoid creating loopholes. She wants to significantly bulk up the resources available to the IRS to police tax avoidance. And Warren wants her wealth tax to apply globally, so as to cut down on efforts by the wealthy to simply move their money overseas.

More broadly and ambitiously, Saez and Zucman propose ideas like a global wealth registry, built on international cooperation, to track and police wealth holdings, and to enable a more coherent international taxation regime.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The underlying challenge is that dealing with tax evasion boils down to political will, influence, and discipline. Over time, either your lawmakers allow lobbyists to blow loopholes in the tax code, or they don't; either they continue giving tax authorities the resources and funding they need to crack down on avoidance, or they don't; and so on. Critics of wealth taxes such as Summers are essentially invoking a skepticism that the necessary political will can ever be mustered, while champions of wealth taxes like Warren and Sanders think these proposals can be used to muster the political will where it once was lacking.

Finally, to go one more layer down, mustering the political will to impose a wealth tax inherently involves combating the political leverage and influence that mass concentrations of wealth represent. The more a wealth tax is successful, presumably, the more political force can be mustered to preserve and protect it.

This gets to one other complication: Is revenue really the best measure of whether a wealth tax is working?

Most everyone both in favor of and opposed to wealth taxes assumes their purpose is to raise the money that will then pay for big spending programs. But the U.S. federal government is the source of all U.S. federal currency — it can "print" as much money as it wants. "For the federal government, taxes are not about raising revenue, taxes are about reducing consumption to prevent inflation," as economist Dean Baker recently put it. And there's a critical distinction between how much money a tax brings in and how much aggregate consumption it affects in the economy: "Do we think this additional tax bill will reduce the number of times Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos goes out to dinner," Baker asked. "Will they take fewer vacations or buy fewer cars, planes, and yachts?" The effect on consumption won't be zero, but it will be far lower than the effect of the same amount of money taken out of a broader and less wealthy group of taxpayers.

Essentially, a wealth tax wouldn't really be about financing government spending or holding down inflation. It'd be about changing the structure of the economy, and ownership in particular: Are companies owned by a small number of rich shareholders, or a bigger number of rich shareholders? Do politicians need to get donations from a small number of rich people, or a larger number of less rich people? Who gets to control decision-making in the economy, and how much power do they wield?

If a rich person sells one set of financial instruments and buys another somewhere else to avoid a new wealth tax, that's not necessarily a problem. If that rich person sells off a factory or a business to move their money, that presents more of a quandary. But whether that sale is good or bad depends on what happens next: Is the business ended (Along with the jobs it represents?) or does it simply change ownership? Is it sold to a more socioeconomic diverse group of owners with different prerogatives? Given the right conditions and surrounding policy changes, could it be sold to the workers themselves? Those latter results would ultimately be better for American democracy.

None of this is a slam dunk argument in favor of a wealth tax. For example: Baker is also skeptical of wealth taxes, because he fears they'll encourage more people to become lawyers and accountants in the tax evasion industry, when our society could make better use of their talents elsewhere.

But to decide a wealth tax's worth, these are the questions we should be asking.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred