Are the trades really the economy's best kept secret?

The story is a little more complicated than the headlines

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One lament that pops up pretty regularly in the business and economic press is that jobs in the trades don't get enough love. The story goes that careers like plumbers, electricians, carpenters, machinists and mechanics offer upper-class wages without requiring a college degree and the accompanying debt load. But thanks to ignorance and a blinkered cultural obsession with four-year college degrees, the trades are going overlooked when Americans choose their career paths.

Does this story actually check out, though?

"There's no doubt that a person — especially someone with formal apprenticeship training — can do quite reasonably in a skilled trade," Dale Belman, a Michigan State University economist who specializes in construction labor markets, told The Week. "That's not news to anybody." But this point also comes with a ton of caveats, from the state of the labor market, to whether or not the job is unionized, to the particular qualities and challenges of work in the trades.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For example, let's zoom out to the national level for a moment, and look at median pay for the jobs that generally fall under the umbrella of the trades. One or two outliers pay between $60,000 and $80,000 a year, and a few between $40,000 and $50,000. But the vast majority pay between $50,000 and $55,000 a year, compared to a national median income for households of over $61,000.

That certainly doesn't mean pay in the trades is bad — $55,000 a year is nothing to sneeze at — but it's certainly not the six-figure paydays that news stories sometimes advertise. Rather, as a career path, the trades appear to be right down the middle.

Obviously, underneath those national figures, there's a lot of variation. Bigger salaries do happen, but they require pretty particular circumstances.

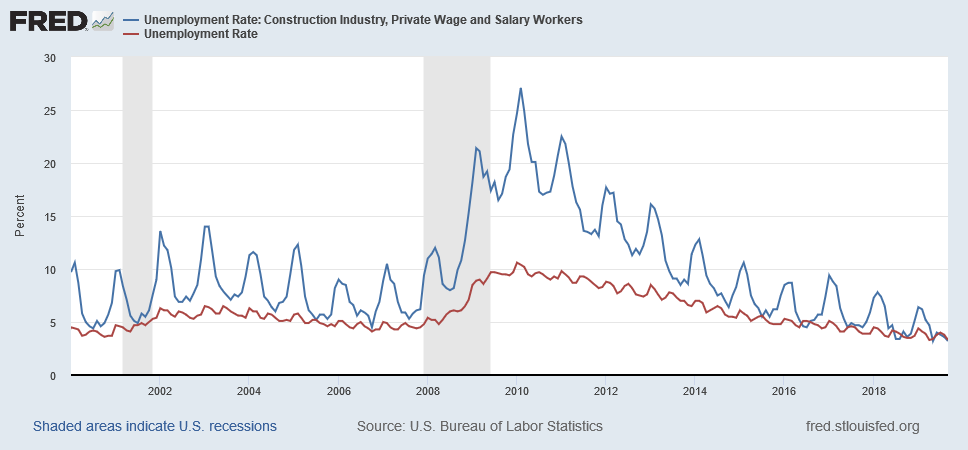

For one thing, the trades tend to be pretty seasonal. As you can see in the graph below, the unemployment rate in construction (the blue line) bounces up and down several percentage points compared to overall unemployment (the red line). The graph also shows how the trades are particularly sensitive to the business cycle, and were absolutely decimated by the 2008 crisis. "During the Great Recession we blew about two million construction workers out of the construction labor market," Belman said.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Granted, that crisis hit construction especially hard, thanks to the role of mortgage-backed financial engineering. But even after the stock-bust of 2001, unemployment in construction peaked at 14 percent. A good-paying career path doesn't count for much if you're out of work half the time.

Unions also still play a pretty big role in the trades. Many of the trade unions and the companies they've organized work together to run very involved apprenticeship programs that are officially registered under the U.S. Department of Labor. Those programs typically run four years, after which the apprentice is a full-blown tradesman or tradeswoman, earning full pay, and moving through a labor market whose job offers have typically been organized by collective bargaining. Meanwhile, there's also a big part of the construction and trades labor market that isn't unionized. Companies in the non-unionized part have also tried to organize certification programs, but they tend to be much less involved — say, a slideshow the applicant works through on their own. And of course, the latter workers don't benefit from the unions' collective bargaining leverage.

As a result, the gap in pay between the union and non-union workers can be pretty big. Belman used electricians in heavily-unionized eastern Michigan versus those in non-unionized western Michigan as an example: Put together pay and benefits like pensions and health care, and compensation for the unionized workers can be twice that of their non-unionized peers.

We tend to assume that high pay is a sign of a labor shortage — demand for workers outpacing supply to a greater degree. But while those forces matter, labor markets are rarely "markets" in the technical way economists mean. They're social institutions, structured by laws and contracts and the bargaining power of the players involved. According to Belman, the significant labor shortages in the trades actually tend to happen in the non-unionized regions with lower pay: "There's a belt of labor shortages running from North Carolina across to Texas," Belman said. "That's also a heavily non-union area with particularly low wages and a lack of effective training systems. So they neither have the ability to train, nor are the jobs conducive to bringing in workers — because there's a lot of traveling in construction."

It's also worth noting that human beings are just different, with various interests and preferences and comforts. Like every other career, the trades are not for everyone. You have to enjoy physical labor, and you have to enjoy working outdoors. These are also jobs that are hard on the body: you'll likely retire early, and with more health problems than most. That makes having generous health coverage and income support in retirement all the more important — and those are difficult things to achieve even under the best of circumstances these days.

On the flip side, one big advantage the trades can have over the college career track is the startup cost of entering the workforce. The debt people take on to finance a four-year or graduate degree has turned into a spiraling national crisis. By comparison, the cost of entering a registered apprenticeship program in the trades is usually, well, zero. The companies who participate in the programs kick in the money to fund them. But again, this isn't quite as great a deal as it first appears.

Recall the graph above: the unions and the apprenticeship programs are dealing with a jobs market that can fluctuate pretty wildly. Thus, they tend to restrict the number of people they take on, so as to avoid creating circumstances where there are way more tradespeople looking for work than there are opportunities to work. "They don't train for the peak of the labor market; they kind of train for an average labor market," Belman explained. And after a massive crash like the Great Recession, they'll be particularly conservative about how many people they let into the pipeline.

There's also often a soft bigotry involved when people present the trades as an alternative to a college-driven career path — a kind of implication that if you can't hack four years of college, you could always become a plumber or such. But even if these jobs don't require a college degree, that doesn't mean they aren't demanding. Entering an electrician apprenticeship program, for example, often requires a B or better in Algebra II. Pipefitters and HVAC installation and repair and other such jobs require knowledge of digital technology these days.

Furthermore, the companies in the trades are looking to hire workers with maturity and dependability, just as much as the companies who insist that their hires have at least a bachelor's degree. "It's not clear that most students coming right out of high school are really ready for an apprenticeship," Belman said. "Some 18-year-olds are great. Some of them need a little more seasoning."

Of course, a person could always try to enter the non-unionized trades to get around those barriers to entry. But then they'd also be giving up the union infrastructure that makes the trades a well-compensated career path to begin with.

This all introduces an interesting political irony. Conservatives tend to be particularly big fans of the story that the trades are overlooked: It's a narrative that appeals to Republicans' sense of themselves as the party of the forgotten blue-collar working man, and it appeals to conservatives' increasing cultural hostility to universities and higher education. Yet Republicans are also rabidly anti-union, and they prize low inflation and balanced federal budgets far above full employment. And if we want to actually expand employment in the trades, we should arguably be empowering and expanding unions, plus remaking fiscal and monetary policy to do much more to prevent and soften recessions.

I asked Belman directly if he thought America's educational system was diverting people away from the trades out of an obsession with the college track. He suggested the problem may exist, but it's not all that severe. "Now that the trades are making a point of going around and talking about it, a lot of high school counselors are coming to realize this isn't just a place you send your kids who don't know what they're doing," Belman said. "It's a good career for students who know what they want to do and are dedicated, but college may not be their thing."

Trade associations already have curricula packages they're offering to high schools, and various pre-apprenticeship programs already exist. And Belman noted experiments like a vocational academy in San Jose, where blue-collar tracks like plumbers and electricians intermingle with white-collar tracks such as engineering and architecture — all in a single program, and thus hopefully cutting down on the cultural stigma.

We could, of course, always do more. But barring some fundamental material changes — a massive expansion of unions' reach, and an overhaul of national macroeconomic policy — the trades will probably remain just one more career option among money, as opposed to an overlooked golden ticket.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred