A racial turning point

In 1960s Louisiana, a black football player developed a bond with a Japanese-American coach. Decades later, that player came back to run the parish's schools.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in The New York Times. Used with permission.

Eunice, Louisiana — Before two-a-day football practices began in August 1969, coach Joe Nagata gathered some of his white senior players at Eunice High School. He told them to prepare for workouts more difficult than usual in heat and humidity that felt like damp clothes inside a dryer.

Desegregation by federal mandate was approaching belatedly and nervously in my rural hometown on the Cajun prairie, 2.5 hours west of New Orleans in St. Landry Parish.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Fifteen years had passed since Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the landmark Supreme Court ruling, declared racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional.

Neil Armstrong had walked on the moon a month earlier. Finally, black students from Charles Drew High School were, by court order, to fully integrate Eunice High School as summer turned to fall.

"We don't know these other young men," Nagata said of the arriving black players, according to Coleman Dupre, our star white running back. "We have to find out who is willing to pay the price."

Integration happened uneasily at Eunice High School, after prolonged white resistance. A spasm of violence convulsed the school just as classes began. But despite initial wariness, desegregation also provided the beginning of a decades-long bond between a coach and a player that belied the Southern archetype.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

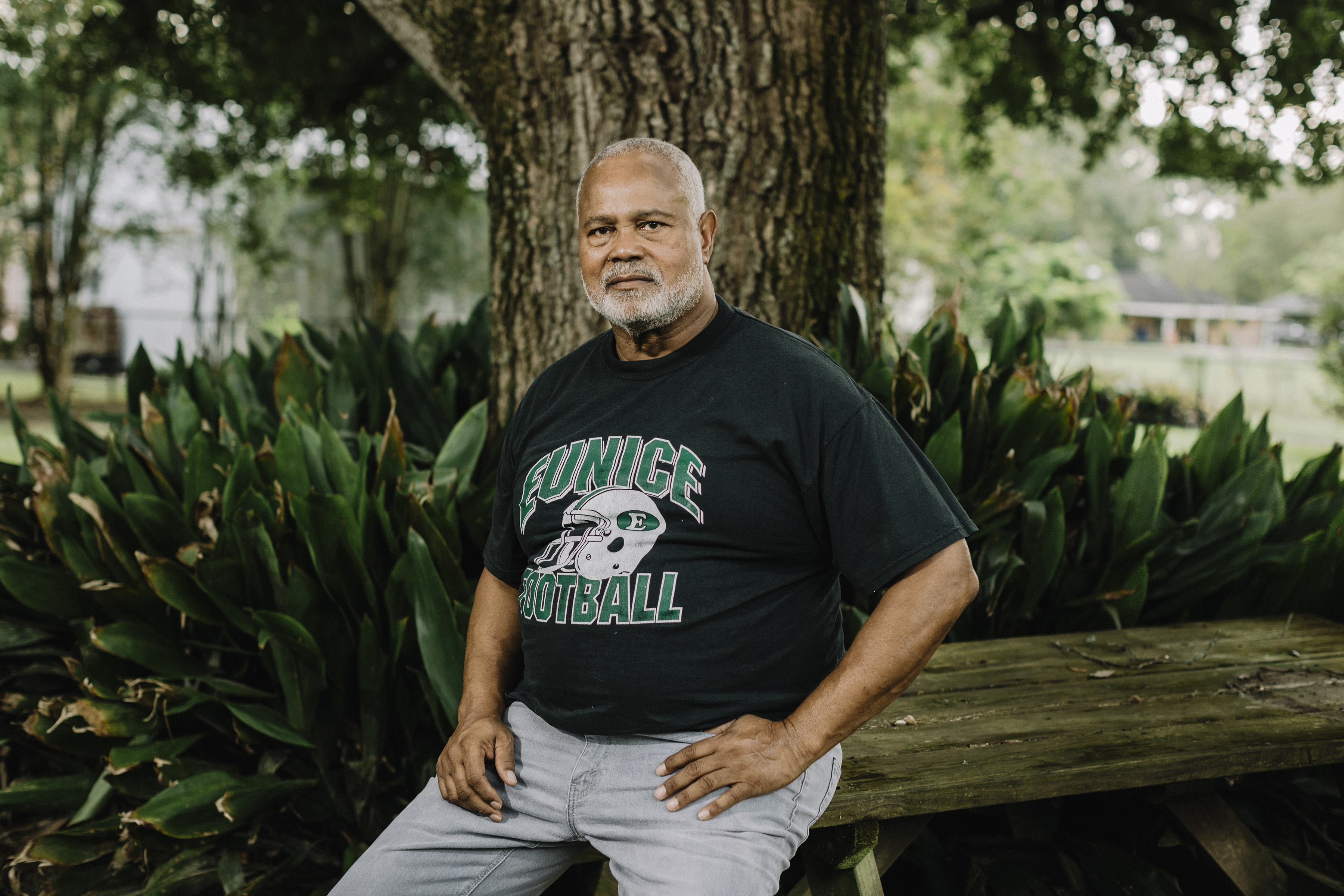

Nagata was a Japanese American who endured racism and suspicion of the other during World War II. And Darrel Brown was a black player who became a teacher, coach, principal, and, in 2013, the first African American elected as the full-time school superintendent of St. Landry Parish.

It was a relationship I learned about as a sports reporter for The New York Times while examining the 50th anniversary of desegregation at my high school. It was a vital friendship that continued until Nagata died in 2001 at age 77. And it illustrated race relations in Eunice over the past half-century: the systematic separation of a bygone era; the ever-evolving change today; the essential but imperfect progress that unspools ahead, kinks and snags, then untangles and casts forward again, hopeful and complicated.

Darrel's parents and a number of black mentors strongly influenced him. His father was a teacher, his mother a librarian. His mother was so proud when Darrel became assistant principal of Eunice High School in 1999 that even though she was gravely ill, she visited his office in her robe and nightgown. But he also developed a lasting connection with Nagata at a transformative moment in Eunice and across the South, when the line of scrimmage became a front line of a profound new social order.

"Coach Nagata inspired me," Darrel, now retired at 66, told me recently over a long lunch and dinner of shrimp and crawfish.

Change begins

Darrel and I did not know each other in 1969. He was a senior; I was a sophomore. He was a starting defensive lineman; I was a backup center who played mostly on the junior varsity. He is black; I am white. We grew up about a half-mile apart with lives that were separate and unequal, governed by restrictions on who could live in what neighborhood, swim in what pool, sit in what section of a movie theater. Segregation was so entrenched in my naïve boyhood that I thought the "Whites Only" sign at the laundromat referred to the color of clothes.

Then, everything changed that August. Black players and white players dressed in the same locker room, showered in the same showers, challenged one another for positions on the line and in the backfield. We were wary of each other, no doubt. But we were also small-town teenagers trying to bond as a team in an apprehensive meritocracy of helmets and shoulder pads.

Nagata showed great loyalty to his players but was said to have had complex feelings about desegregation. Coleman, our running back, told me the coach resented what he considered social "entitlements" for blacks, feeling he did not receive the same support when facing bigotry himself as a teenager and young adult during World War II. He added that Nagata later grew frustrated, feeling he was not permitted to discipline black students as he could white students.

Yet as a Japanese American, he had also yearned to be treated equally and felt that everyone should be treated with dignity. "He had an understanding of what blacks had gone through growing up, dealing with prejudice, given what he and his family had to put up with," Coleman said.

Nagata was a senior at Eunice High School and an all-state running back in December 1941 when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. The FBI closed his family's produce store for a day and a half, seized more than $400 in cash and checks — equivalent to more than $6,600 today — and confiscated a Philco radio with a shortwave band.

The coach's father, Yoshiyuki Nagata, who immigrated to Chicago from Japan and eventually settled in Louisiana, was arrested and held overnight and the family car was impounded, according to a history of early Japanese American athletes in Louisiana. Nagata's children said they had never heard that story. In any case, their father's athletic career proceeded.

In 1942, Nagata received a scholarship to play football at Louisiana State University. On Jan. 1, 1944, he played a key role in LSU's victory in the Orange Bowl, then joined the military. He was awarded a Bronze Star for his service in Italy in a highly decorated unit of Japanese American soldiers called the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

After the war, he played again at LSU. In an oral history project, Nagata said his teammates and fellow students were "overly nice" to him in understanding that he and his family "weren't spies or anything like that."

Through the years, though, stories persisted in Eunice that not everyone embraced him, that he had been subjected to jeers from spectators and racial slurs from opponents. Darrel remembers Nagata talking to our high school team in 1969 about his time at LSU, "about going out on the field, getting things thrown at him, getting booed."

"I think he tried to correlate that with integration," Darrel said. "He was letting us know that he had been through a similar situation. He was giving us a sense of security that things were going to work out."

An explosive first season

The 1969 football season began as scheduled, and school opened edgily after white protests around St. Landry Parish. Still, there had been no wholesale white flight in Eunice, no rush to build so-called segregation academies. Black teachers, surely given little choice, had accepted less than a 50-50 apportionment at Eunice High School. Leadership in the school, black and white, was strong and committed to discipline and tolerance.

But a fragile calm combusted on Sept. 22. A white student walking to class came upon a fight in a hallway. He was stabbed in the left side by a black teenager from Baltimore who had apparently not registered for classes. As belts with sharpened buckles were swung, Johnny Alfred, our team's best black running back, grabbed Coleman, our top white back, and pulled him to safety.

The fight might have carried over from racial skirmishes at our football game three days earlier, officials believed. By midmorning, the high school was closed. Football players were commended by the principal for calming the students and preventing further trouble. Yet, when school reopened the next day, nearly 400 of the 500 white students were absent.

Local police officers, state troopers, and FBI agents converged on Eunice High School after the stabbing. Threats were made to burn down the school and black neighborhoods. Nagata received anonymous threats and put steel plating in the front windows of his house, just in case, his children said.

Eunice was placed under curfew. Local and federal authorities spent several nights inside the school. After a week or so, most white students returned. An anticipated exodus did not occur. But the atmosphere remained tense. I remember students being frisked for weapons in physical education class and teachers carrying whistles to blow if fights broke out.

The football team continued to play, serving to defuse tensions. Darrel, a 6-foot, 185-pound defensive guard, was nicknamed Bear for his thick chest and deep voice, but those who know him can hardly remember him raising it. He and others became peacemakers.

"The football players were sort of referees in the halls," Darrel said. "We got between a lot of things."

I feared and revered Nagata. He was strict, and when we disappointed him, he tugged at his shoulders and said, "Crap, damn, hell." He sometimes grabbed our face masks and shook them or shivered us with a forearm to the chest. Some teammates remember him with a towel around his neck, as if he were managing boxers instead of football players. I remember him wearing a white dress shirt and tie on the sideline with his glasses, which suggested studiousness and diligent preparation.

He had a sly humor, too, telling his coaching friends to console themselves after a defeat with "two aspirins and a six-pack; if you don't have aspirins, don't worry about it."

Regarding Darrel, Nagata and his staff clearly saw something special in him. David Greer, a white assistant who grew up as a Catholic in Birmingham, Alabama, and experienced cross burnings in his yard by the Ku Klux Klan, gave Darrel rides to preseason practices. Later, he and Nagata gauged Darrel's interest in attending a predominantly white college in Louisiana, where he would have been among the early black football players.

"They saw something in me that maybe I didn't see in myself," Darrel said.

After that 1969 season, Nagata and Edmund Saucier, the Eunice High School principal, asked Darrel and other black players to speak candidly about their experiences with desegregation.

Darrel asked why the quarterback who had been the starter at Charles Drew High was not given the same opportunity at Eunice High, touching on a corrosive stereotype that black athletes were not smart enough to be quarterbacks. Nagata said he chose a white quarterback based on experience, not race. The white quarterback had played in his system for three years. Darrel said he accepted the answer and appreciated being able to speak openly.

"I had never had dialogue like that with the principal," he said.

Still, the early years after desegregation were fraught with strain that veered into tragedy on Feb. 11, 1972. A fight broke out in a dimly lit parking lot at Eunice High School after a basketball game. A senior by then, I remember leaving the gym and seeing a trash can arc through the air like the jettisoned stage of a rocket.

The next morning, Nagata phoned me and other football players with grim news. The brawl had led to a stabbing. A white teenager from the visiting school had been nicked in the heart and died in the night. Come to school, coach told us, and help look for the knife. We never found it.

Our best football player, who was black, was arrested and spent a week in the parish jail before being cleared and released. Nagata visited him regularly, my teammate told me, and even brought him cigarettes.

While my teammate was cleared, another black student — Darrel's 16-year-old brother — was indicted on charges of unlawful killing and battery with a dangerous weapon, according to court records. But the evidence was apparently considered insufficient, and the charges did not hold. The case was sent to juvenile court, and the file remains sealed. Darrel's brother received probation after pleading guilty to a count of juvenile delinquency, according to news reports in the highly publicized case. He has long maintained his innocence in the knifing.

What happened that night in the school parking lot remains unclear. Darrel said he was certain that his brother did not stab anyone. At the time, he added, he felt both relief for his brother and "very sad" that a life had been taken. "I was sorry for the family," he said.

Darrel was midway through college at Grambling State, where he did not play football, building toward a career of keeping black and white students together. An important moment for him occurred in the early 1990s. By then, Nagata was retired and serving on the St. Landry Parish school board. He showed up unannounced at Eunice Junior High School, where Darrel was the head football coach, and said, "Don't have me call your name for something and you're not prepared."

Then Nagata urged Darrel to get his master's degree. His words were cryptic, but Darrel understood them to mean that administrative positions would soon open. Nagata's encouragement, Darrel said, "lit a fire."

He had not aspired to become the parish school superintendent, Darrel said, but "when doors started to open, I walked through them."

Nagata did not live to see Darrel run the county schools. He resigned from the school board in declining health in 2000 and died a year later. At a memorial service, Darrel fought back tears.

"He was a true friend," Darrel said.

In 2013, Darrel became superintendent and served until late 2016. He was known officially by his first name, Edward, though in Eunice he is widely known as Darrel, his middle name. He presided over one milestone achievement: overseeing the dismissal by a federal judge of the 47-year-old school desegregation order in St. Landry Parish in September 2016.

His career had completed a singular arc: He attended segregated Charles Drew High School, graduated in the first fully desegregated class at Eunice High School, and headed the parish school system nearly a half-century later when it was released from federal oversight.

Home today

My mother, a former secretary at Eunice High School, still lives in the house where I grew up. I have fond affection for my hometown — the bonhomie, the shrimp and okra gumbo, the Eunice High football team that won state championships in 1982 and 2018 and effectively renovated the school into a museum of civic pride.

But Eunice is also a stressed place today. It lacks industry, is vulnerable to fluctuations in the oil, rice, and soybean markets, and is geographically stranded along U.S. Highway 190, 20 miles north of Interstate 10 and 20 miles west of Interstate 49. It feels passed by, someplace traveled through to get to someplace else.

Eunice's population, which peaked at about 12,500, according to the 1980 census, dipped below 10,000 by 2018 estimates. Eunice High School has about 650 students; it once taught 1,100. Thirty percent of Eunice's residents live in poverty; more than 20 percent of those younger than 65 do not have health insurance.

The subject of race, as in many places, is not easily discussed and yet ever-present.

Eunice High School did not sponsor an integrated prom until 2004. After more than 150 black students walked out of class in 1980, protesting that a vote for homecoming queen was unfairly tilted toward whites, no queen was chosen again until four years ago. Despite efforts by the principal to recruit minority faculty members, there are two black teachers now at the school, compared with 10 in 1969.

At the same time, among traditional public high schools in St. Landry Parish, Eunice High School offers the highest-rated education, according to a 2019 ranking by U.S. News & World Report. In many ways, desegregation has worked as intended. There is one public high school in town, and the student body — 55 percent white, 43 percent black, 2 percent Hispanic — still roughly reflects the racial makeup of the city. Black students have been named valedictorian, Mr. and Miss Eunice High and, yes, homecoming queen. Eight of the 10 members of this season's homecoming court are African-American.

The Bobcats won their two state football championships with black quarterbacks. Football confirms that Eunice measures up to surrounding towns. It is also a kind of municipal mirror that reflects the city onto itself.

"It's gotten a lot better, but racism is still alive," Darrel said.

In January, a high school student at the local Catholic school was told to apologize by the diocese after he posted a photo on social media showing white teenagers with boxes of fried chicken and a caption that said, "Happy MLK Dayyyyyyyy."

In a larger sense, though, 1969 seems to have receded far into segregation's rearview. What formerly seemed extraordinary is now commonplace. Black and white students wait for the bus in neighborhoods once strictly segregated. There is easy mingling at restaurants where separateness is no longer on the menu. A black player giving his white girlfriend a kiss in the hallway at Eunice High School brings only an admonition to hurry on to class, not the racial confrontation that surely would have erupted a half-century ago.

In December, as Eunice High School moved toward inexorable victory in the state championship game, Xavier Sharlow, a black tackle, turned on the sideline to Lane Devillier, a white tackle, and said, "Love you all, man."

Opportunity is the overarching difference, Darrel said.

"You're not looked down on anymore," he said. "You're looking eye to eye now."