Baghdadi's death is not a triumph

Before America killed Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, it helped him rise

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is not the victory it appears to be.

Instead, his grisly demise during a raid in Syria by U.S. commandos — announced in football-spiking fashion Sunday morning by President Trump — is a reminder that when America ventures abroad, we sometimes help create the monsters we later feel compelled to destroy, starting a loop of self-justification that results in an endless string of "forever wars."

Don't misunderstand: Baghdadi was evil. Under his leadership the Islamic State beheaded hostages and violently imposed the worst sort of theocratic rule wherever its caliphate could be established. He kept sex slaves for his personal gratification — including, reportedly, U.S. hostage Kayla Mueller. It is impossible to mourn him.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But while Americans celebrate Baghdadi's death, they should also think critically about his life — and see it as a cautionary tale against U.S. meddling in Middle East affairs.

Here is how the math works: In 2003, U.S. forces invaded and occupied Iraq. The occupation spawned the creation of Al Qaeda in Iraq, which eventually evolved into the Islamic State, with Baghdadi at its head. His rise to bloody power was the direct result of America's choice to go to war against Iraq and its leader, Saddam Hussein.

"At every turn," The New York Times noted in 2014, "Mr. Baghdadi's rise has been shaped by the United States' involvement in Iraq."

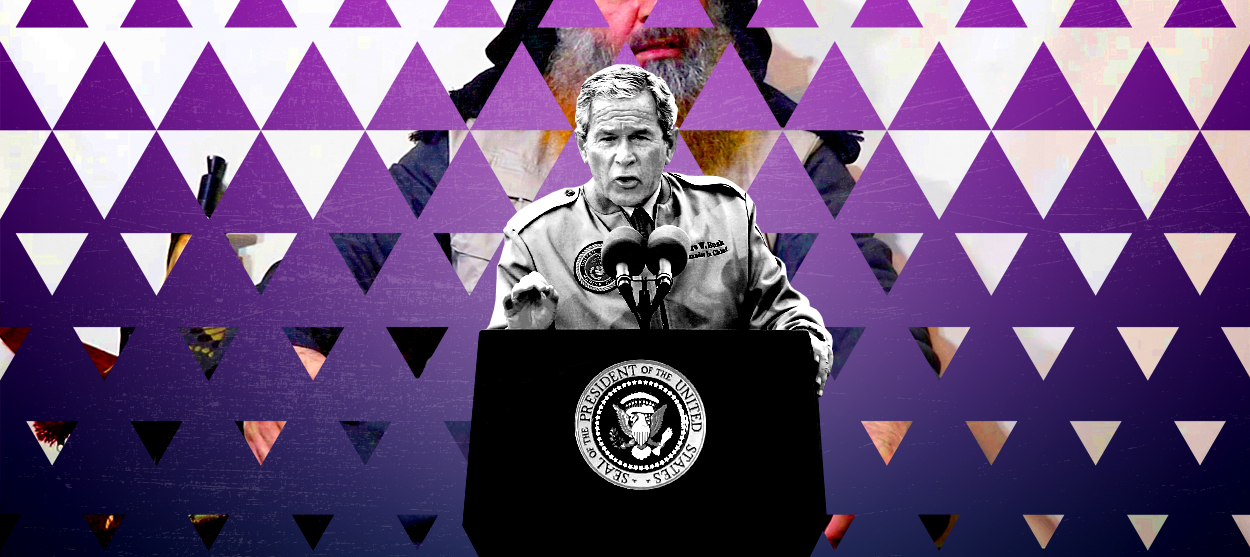

Remember, America's invasion of Iraq was a choice — an unforced error by President George W. Bush and his happy band of neoconservative hawks. Americans in 2003 were still in a fighting mood after the attacks of 9/11, and while Iraq had nothing to do with that event, Bush's advisers almost immediately decided it was close enough. They justified the unprovoked invasion by citing the dangers of Hussein's weapons of mass destruction program — a program that was discovered to be virtually non-existent after American troops took over the country.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Much of what has happened in Iraq and the surrounding region since then is the story of America's attempt and failure to contain the consequences of that mistake.

Baghdadi was already of a fundamentalist bent, but the occupation of Iraq further radicalized him. He joined Iraqis and thousands of Muslim fighters who converged on the country to fight with Al Qaeda in Iraq as it led the bloody insurgency against American troops. One incident during that time period may have further inflamed Baghdadi's violent tendencies: He was arrested and imprisoned at the U.S.-run detention facility at Camp Bucca. The prison, The Washington Post reports, "served at times as a recruitment and training center for jihadists."

"Extremists mingled with moderates in every compound" which "fueled the insurgency inside the wire," an observer later wrote in 2009.

Baghdadi rose to become one of Al Qaeda in Iraq's senior leaders, then guided the organization as it evolved into the Islamic State, which fought for — and for a time established — a caliphate covering parts of Iraq and Syria. He led the group when it beheaded journalist James Foley in 2014, and as it enforced Islamic law with "public floggings, amputations, and executions."

America didn't create Baghdadi. It did, however, create the conditions in which he rose to prominence and power as a vile and violent man. Without U.S. adventurism in and around the Middle East, it is possible that Baghdadi would have lived and died relatively peacefully, an unknown "austere religious scholar" with unimportant views. Instead, his life and death are more consequences of America's disastrous decision to go to war nearly a generation ago.

"He was a street thug when we picked him up in 2004," a Pentagon official told The New York Times in 2014. "It's hard to imagine we could have had a crystal ball then that would tell us he'd become head of ISIS."

In the aftermath of Baghdadi's death, that isn't the story you will hear from America's foreign policy establishment. Instead, the hawks are using the commando raid to advocate for unending empire.

"We must keep in mind that we were able to strike Baghdadi because we had forces in the region," said Rep. Michael Waltz, (R-Fla.), after Trump announced Baghdadi's death. "We must keep ISIS from returning by staying on offense."

Going on offense is how we got the Islamic State. If you step back and look at U.S. policy over a 20-year timeline, you recognize the logic as endlessly circular: We must have troops in the Middle East to neutralize threats to America that might never materialize if we didn't have troops in the Middle East.

Criticizing the hawks' argument does not amount to an endorsement of the foreign policy of Trump, whose "now-we're-leaving-now-we're-not-now-we're-taking-the-oil" approach to Syria has managed to make a violent and chaotic region somehow worse.

Despite what you will hear from the hawks over the next few days, Baghdadi's death is not proof of the wisdom of American interventionism. Quite the opposite. When we go looking for enemies to fight, we will usually find them. Maybe it is time to stop looking.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military