Capitalism without consequences — for the rich

What the collapse of Deadspin has in common with WeWork and Uber

Deadspin, the wildly popular sports website, is a smoking ruin. After a dispute with its new ownership, G/O Media, over intrusive autoplay ads and oafish demands that its writers "stick to sports," the brass fired beloved deputy editor Barry Petchesky. Most of the rest of the staff have since resigned in protest.

The peculiar thing about this dispute is that Deadspin was and always had been a profitable, successful business, and the primary complaint from the staff was that ownership was screwing up the money machine. Deadspin's non-sports writing got better traffic than its sports coverage. Autoplay ads with sound are traffic and brand poison, and many advertisers don't even request them anymore — indeed, they were reportedly a desperation tactic to deliver ad impressions to Farmers Insurance the owners had sold but could not deliver. (In a dark irony, Farmers has since pulled out of the deal.)

Nevertheless, it's a safe bet that Jim Spanfeller, the private equity goon in charge of G/O Media, and the rich white men he brought with him to run the business, will not be ruined by this. Indeed, he already belly-flopped on his two previous media projects, seemingly not understanding that the online ad market had changed radically since he made bank turning Forbes.com into a bargain-basement content mill in the late aughts. Now he's made the same mistake again.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Elsewhere in the business landscape, a variety of companies are losing immensely larger piles of money than all the former Gawker Media websites have ever touched in their entire existence. Capitalism is not working as advertised.

Take WeWork, the money-torching property management start-up — hemorrhaging $2.9 billion between 2016 and 2018 — that tried to do an initial public offering earlier this year, only for its valuation to collapse and the IPO to be canceled after actual experts started taking a hard look at its books.

Then there are Uber and Lyft, the taxi companies who have both lost incomprehensibly vast sums. As of mid-2019, Uber had lost something like $14 billion in the last four years, while Lyft lost approximately $2.3 billion between 2016 and 2018 — with losses continuing even after both companies went public. Just in the second quarter of 2019 Uber posted a loss of $5.2 billion. Lyft, meanwhile, boasted that it "only" lost $1.57 per share in the third quarter of 2019, with investors reportedly encouraged by a plan to achieve profitability by 2021.

In retrospect, once again the odd thing about all three of these sucking cash voids is that their business models never made any traditional business sense. As Hubert Horan writes in a hard-nosed analysis at American Affairs (and Mike Isaac covers in his brilliant book Super Pumped), the taxi business is wholly unsuited to the kind of tech-based explosive growth that companies like Amazon and Google parlayed into massive success. Those companies could take advantage of network effects from becoming the main online retailer and search engine respectively, and gain new customers and revenue for tiny additional expenditures.

The taxi business has no such structure. Costs there expand largely in line with the size of the business, driven by the costs of vehicle purchasing and maintenance, fuel, and driver wages. Uber's costs in many of these areas are higher than traditional taxis, not lower, because it shifts vehicle financing costs onto its drivers, who cannot take advantage of economies of scale and lower interest rates, and because it has huge costs from its glitzy headquarters, enormous advertising campaigns, and battalions of well-paid programmers.

As Horan details, while traditional taxi regulations are often over-complicated, those regulations existed for a reason: to allow for a functional taxi system. Previous experiments in taxi deregulation resulted in much greater traffic congestion and collapsing driver pay — something that has been replicated precisely under Uber and Lyft.

Uber only grew to a giant behemoth through two main strategies: first, violating the law — that is, flagrantly disobeying local regulations about how taxis must be operated, including fake versions of its app to trick the cops — and second, heavily subsidized prices. Uber is very popular because people can enjoy a clean, quick taxi ride in a late-model car without having to pay anything like what it costs to provide the service. But all this means that if Uber ever tries to leverage its market power to reach profitability, it will quickly be out-competed on price by regular old taxi services which don't have the overhang of gigantic executive salaries.

WeWork has similar problems. Its goofball former CEO — who was equal parts woo-woo guru and ruthless parasite — was trying to trump up the image of a world-conquering enterprise on the basis of a mature and relatively low-margin business, namely subleasing. Property management is a market with fatter profits than taxis, but also one that does not lend itself very well to exponential growth, because buildings require constant maintenance and servicing (indeed, wraparound business service was part of the WeWork sales pitch). The only way such a business could grow that fast was by selling under cost, and now some hard realities are heaving into view. As marketing professor Scott Galloway told New York, "This is a distressed asset in free fall that is inarguably worth less than zero. Because all we have here is an entity burning $700 million a quarter."

And these are just three of dozens of Silicon Valley start-ups whose business models so far have been to lose money on every sale and make it up in volume. Fully 70 percent of new IPOs are from money-losing businesses.

Needless to say, this isn't how capitalism is supposed to work at all. Libertarians wax rhapsodic about the magic of how the price system provides efficient information about millions of products and the preferences of millions of consumers, but insofar as that actually is a true story, it certainly will not happen in a market in which things are sold for less than their actual cost. (Indeed, even Karl Marx took for granted that a capitalist commodity should sell for more than the price of its inputs.) Actual productive enterprises, like Deadspin, are being driven out of business because they don't have Wall Street backing. Instead of "creative destruction," it's just plain destruction.

It's hard to know just how such an easily-foreseeable spree of business faceplants could happen. One factor is certainly the mouth-breathing gullibility of the investor class (particularly the rubes at the helm of the Saudi sovereign wealth fund), who are easily tricked into dropping billions into anything with a high-tech sheen. Another factor is the combination of gigantic riches pooling at the top of the income ladder and stagnant working-class wages. Investors naturally want some returns on their money hoard, but with most average family budgets tapped out, there is little promising to invest in. It's a recipe for scams.

Reckoning for WeWork and Uber will probably come at some point, but the broader problem will remain. Capitalism is not even providing the virtues advertised on the tin. Perhaps it's time to consider alternatives.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

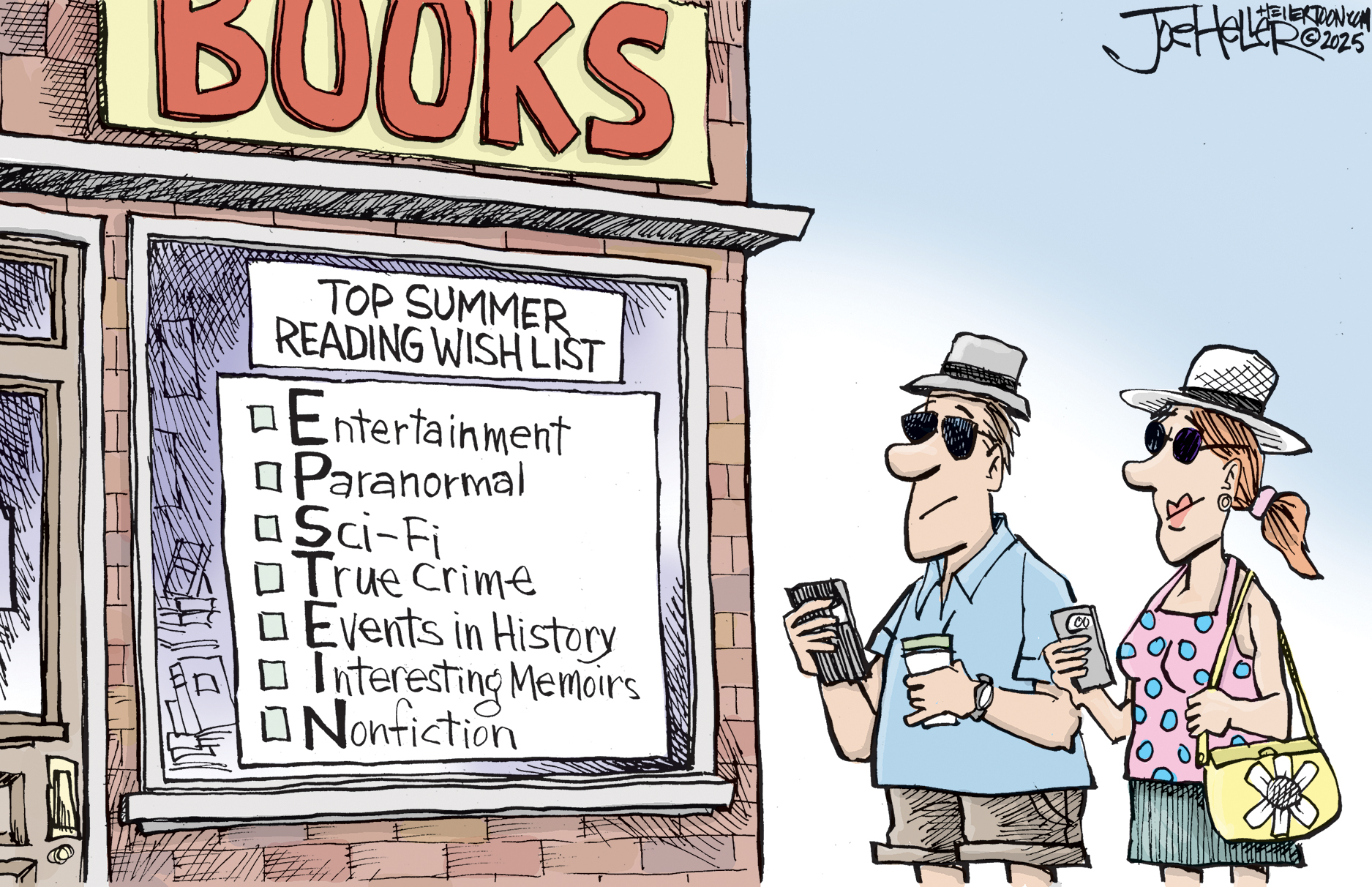

July 16 editorial cartoons

July 16 editorial cartoonsCartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the Epstein files landing on everyone's summer reading list, and the relationship between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin

-

Viktor Orban: is time up for Europe's longest-serving premier?

Viktor Orban: is time up for Europe's longest-serving premier?Today's Big Question Hungarian PM's power is under threat 'but not in the way – or from the people – one might expect'

-

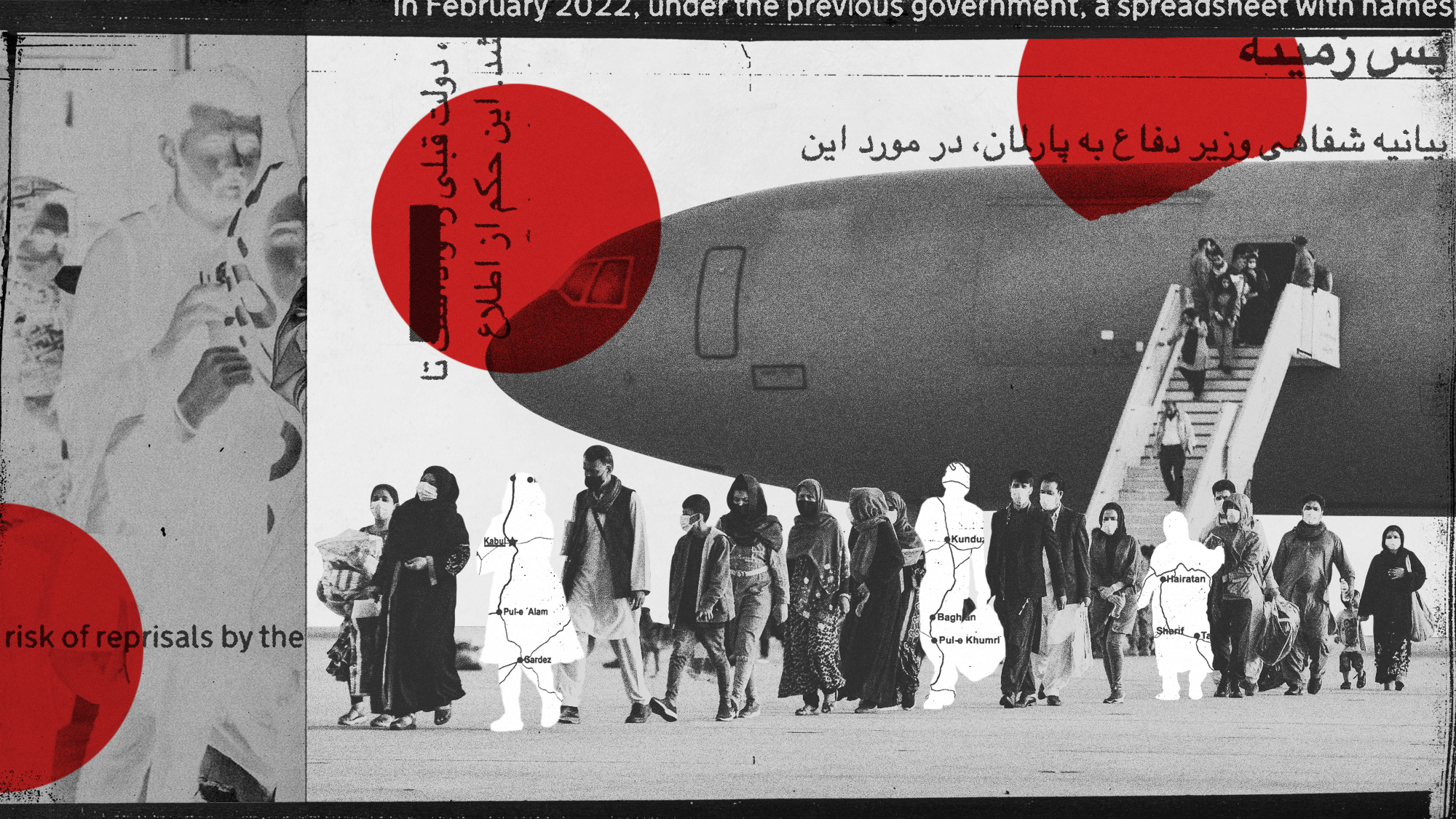

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation scheme

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation schemeThe Explainer Massive data leak a 'national embarrassment' that has ended up costing taxpayer billions

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?