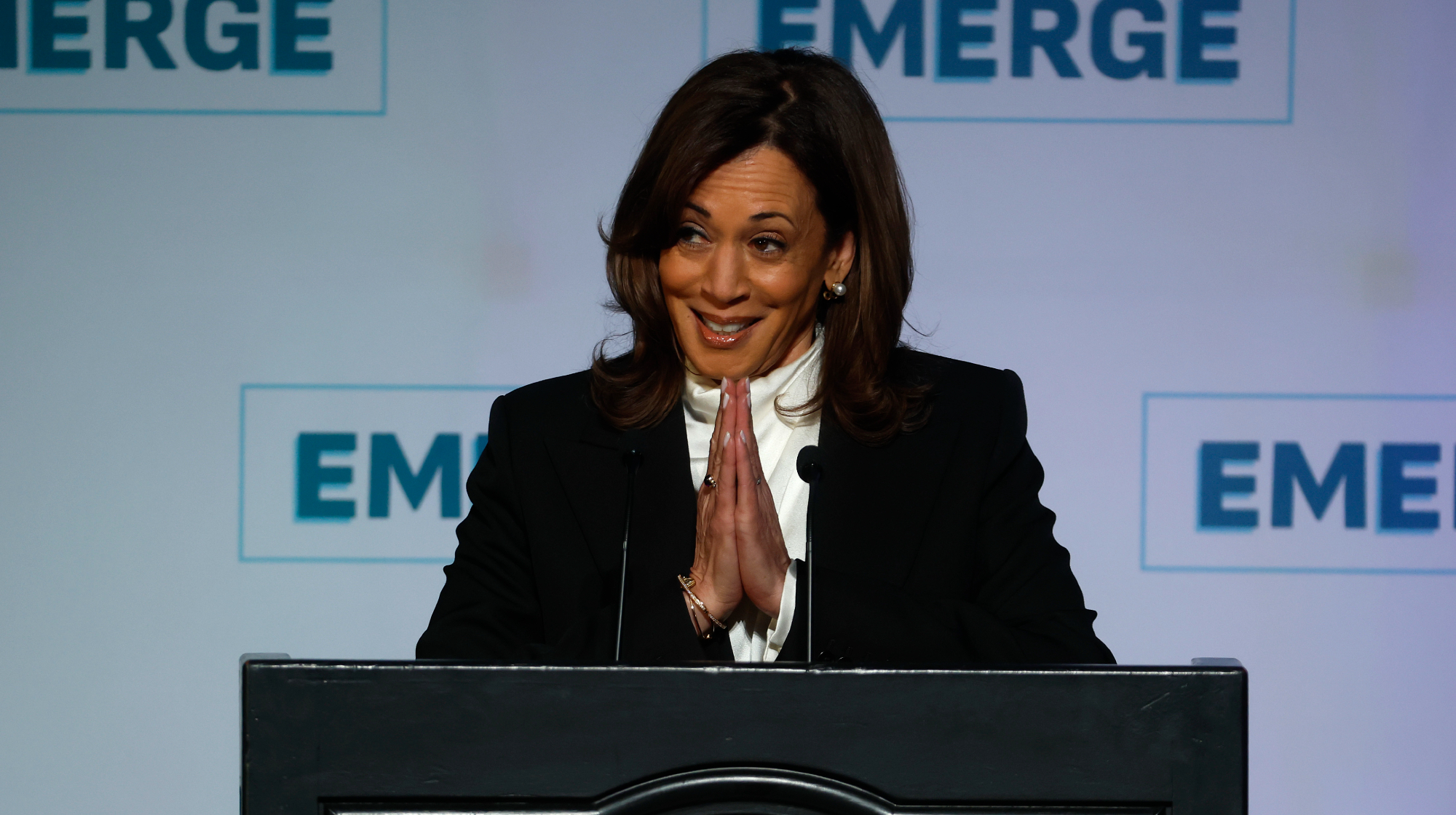

Kamala Harris' 10-hour school day plan is part of a troubling trend

It may not be as radical as you've heard, but we should still be wary

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) is a cop, as the saying goes, which is shorthand for the fact that her present enthusiasm for criminal justice reform was not so much in evidence during her years as a prosecutor. Among the most notorious blemishes on her record is her prosecution of parents of truant children as San Francisco district attorney and her support for a law which took the program statewide in California, landing some parents in jail.

That was the context in which many read Wednesday's Mother Jones report on the Harris campaign's plan for extending the school day to 10 hours, from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. — at least, it's what I had in mind. It sounded like classic Harris: She identifies a situation most would agree is not great and sets about remedying it in a punitive, authoritarian way almost no one likes. We're a week into standard time; the sun sets at like 11 in the morning; and here's Kamala Harris trying to keep kids at their desks for three more hours after dark.

The reality of Harris' plan isn't that radical. Mother Jones describes it as "purposefully vague," a pilot program which funds 500 schools to explore how it would work in their specific community (this localism is a strong point) to "keep their doors open from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., with no closures except for weekends, federal holidays, and emergencies." So it's not simply adding three more hours of class time, but there's still a lot to dislike here. And beyond this particular proposal is the troubling trend it represents, which for whatever reason has received considerably less attention in other Democratic contenders' campaigns.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Harris cast her plan as a fix for two related problems. First, the standard school schedule (8 a.m. to 3 p.m.) does not match the standard work schedule (9 a.m. to 5 p.m.), which presents an often expensive hardship for working parents. Second, this mismatch is an estimated $55 billion drain on our GDP each year.

The latter item is relatively easily set aside. There are no doubt lots of ways we could rearrange children's lives to grow GDP — if we're extending the school day to 10 hours, why not 12? 14? All the hours they're not sleeping? — that we rightly do not give serious consideration. Even if we differ on how the competing goods of economic growth and family time should be balanced and what role the state should play in balancing them, most Americans would agree it is wrong to so value money above the welfare of children. Harris' decision to frame her plan as "an economic growth and child development strategy" — note the order — is off-putting, as it should be.

The first item, however, is more formidable. Harris is correct that childcare is often incredibly expensive; that parents (especially mothers) have to modify their work schedules to accommodate the school day; and that a tiny minority of elementary schoolers (3 percent) and a larger subset of middle schoolers (19 percent) end up unsupervised between 3 and 6 p.m. because there is no after-school care or similar program to watch them while their parents finish work.

Still, there are some significant assumptions in this diagnosis and Harris' response that merit scrutiny. Chief among them is the notion that if school is shorter than work, we should make school longer instead of making work shorter. This is so both individually (many parents may want to leave at 3 to see more of their kids and less of their coworkers) and economy-wide (the average office drone works just three of eight hours in a day, and a shorter workweek has been found to correlate to all sorts of benefits, including the higher productivity Harris wants).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Also unfairly assumed is the wisdom of structuring — and, specifically, permitting the state to control the structuring of — ever more of children's lives. Harris is not the only Democratic candidate moving in this direction. Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) as well as former HUD Secretary Julian Castro all back "a 'community school' model that would provide extended learning time and after-school programs in addition to other social services," the Mother Jones story notes. South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg's terrible mandatory national service idea for young adults arguably belongs in this category, too.

The candidates all have admirable aims with these proposals, like helping working parents, giving kids more education, and fostering volunteerism and social cohesion. But the result in practice is young people spending more time in controlled, institutional settings and less time with their families or on their own, building the skills of independence they need for adulthood. Children need to be let alone sometimes. These plans eat up what little freedom they have.

You don't have to go full free-range parent to find this trend worrisome. Kids' free time is already shrinking, being consumed by longer hours of instruction, after-school care, and other scheduled activities. Unstructured recess time is on the decline, contrary to pediatricians' recommendation, and where recess persists, it is often hedged into inactivity by onerous rules and heavy homework loads. And parents are increasingly subject to scrutiny, including from law enforcement, for statistically safe behavior that was considered perfectly normal a decade or two ago, like leaving a child in the car for five minutes while running into a store or letting them play at a park alone. Making the school day 10 hours long is a huge jump down this road whose destination we frankly do not know.

And don't you remember what it's like to be a kid? Don't you remember how interminable a seven-hour school day felt? How you watched the clock's glacial progress toward 3 p.m.? How badly you wanted to go home and play around as you pleased? Harris isn't necessarily proposing three more hours of instruction — though it seems possible some of her 500 test schools could try exactly that — but she is proposing three more hours where children are required to be at school, doing adult-directed "enrichment activities." She's raised some good questions, but her answer would devour three more hours of childhood 180 days a year.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Ex-South Korean leader gets life sentence for insurrection

Ex-South Korean leader gets life sentence for insurrectionSpeed Read South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol was sentenced to life in prison over his declaration of martial law in 2024

-

At least 8 dead in California’s deadliest avalanche

At least 8 dead in California’s deadliest avalancheSpeed Read The avalanche near Lake Tahoe was the deadliest in modern California history and the worst in the US since 1981

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame game

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame gameFeature Kamala Harris’ new memoir reveals frustrations over Biden’s reelection bid and her time as vice president

-

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Harris rules out run for California governor

Harris rules out run for California governorSpeed Read The 2024 Democratic presidential nominee ended months of speculation about her plans for the contest

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein