The impeachment rules fight is another blowup in the slow destruction of Congress

We have spent the last 20 years coming to an inevitable war between Republicans and Democrats in the Beltway

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

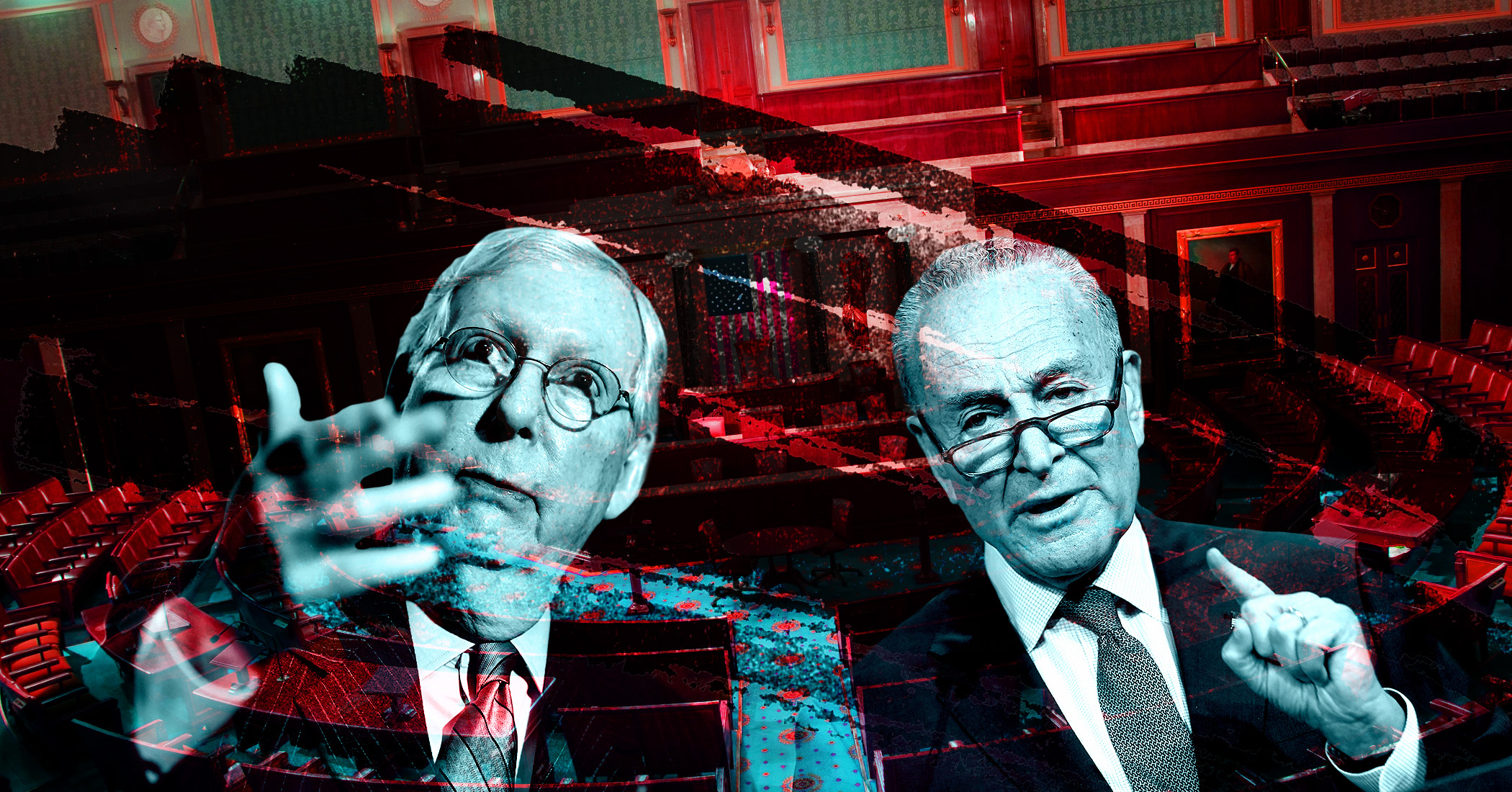

If politics is just warfare by other means, both Mitch McConnell and Chuck Schumer have decided to drag out the heavy artillery in advance of the Senate impeachment trial of President Trump.

The Senate majority leader's rules proposal passed, thanks to the simple majority required, which itself is part of a pitted landscape in the upper chamber after nearly 20 years of partisan one-upmanship. That proposal will govern a process that might be more about settling scores with the House and with the Senate Democratic minority than it has to do with Trump or his handling of Ukraine aid.

One has to wonder just how much of this will have to do with the case against the president at all. It's just as questionable, after three years of impeachment demands from and to House Democrats, how much the push to impeach Trump has to do with a delay in aid to Ukraine. We have spent the last 20-plus years coming to an inevitable war between Republicans and Democrats in the Beltway, one that will determine whether the institutions matter more than party affiliation.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

To grasp this, one needs to walk backward to 1999. Earlier this month, McConnell refused to sit down with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi or disclose his rules proposal to her before she sent over the articles of Trump's impeachment, claiming the House Democratic majority was trying to unduly influence Senate operations. During the three-week standoff, McConnell repeatedly said that he would use the rules package from Bill Clinton's 1999 impeachment trial, which put off any votes on witnesses until after the presentment of the case. That rules proposal got unanimously adopted, including a vote from then-newly elected Senator Chuck Schumer.

Pelosi finally gave up last week and transmitted the articles. By Monday, however, McConnell had adopted a new wrinkle in the Clinton-trial rules. It still used the same framework for voting on witnesses, but McConnell added a section that required a vote on admitting House-developed evidence. In previous trials, the House evidence was admitted automatically. That set Democrats off. They claimed that McConnell was cooking the trial, which might have pushed his grip on the majority just a little too far. By Tuesday afternoon, that rule had been replaced, subject to a hearsay objection and floor vote on specific House evidence.

But what prompted that rule change in the first place? Republicans had seethed while House chairs Adam Schiff and Jerrold Nadler had used their majoritarian authority to largely sideline them in the impeachment process. Rather than go to court to bid for testimony, Schiff and Nadler jammed through the articles of impeachment without any first-hand testimony or evidence of wrongdoing. Republicans saw this as a continuation of the Democrats' efforts to impeach Trump over the earlier Russia-collusion hypothesis, which fell apart after Robert Mueller's special counsel probe found no evidence for the theory.

Part of the animus driving Democrats was the way in which Republicans had muscled their way to Trump's first Supreme Court nomination. Barack Obama had nominated Merrick Garland after the death of Antonin Scalia in January 2016, a nomination McConnell had blocked with his Senate majority at the time. Democrats had at times threatened to do this in the past; Joe Biden in particular mentioned the possibility in 2007 and 1991, but the opportunity never arose for an election-year nomination. Chuck Schumer then attempted to filibuster the confirmation of Neil Gorsuch, which led McConnell to change the Senate rules to eliminate the filibuster on Supreme Court nominations.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And that resulted from Harry Reid's so-called "nuclear option" in 2013, in which he contradicted long-standing precedent to allow a simple Senate majority to change the rules in mid-session. Republicans at that time were using the filibuster to obstruct Obama's appointments to the D.C. Circuit appellate court. That was in payback for Senate Democrats' own obstructionism during the George W. Bush administration on federal judicial appointments, starting in 2002 and leading to a famous showdown and compromise in 2005.

It is this partisan escalation, in Capitol Hill in general and the Senate in particular, which has led the nation to this impasse. Both sides are trying mightily to claim the moral high ground in the impeachment fight and rules debate, but both sides have also done their best to cook the process for their own ends. Georgetown Law professor Jonathan Turley, who spoke in opposition to impeachment on institutional grounds (although no fan of Trump in other respects), concluded on Tuesday afternoon that both parties have run this into the ground. "The tide of hypocrisy washing over the Hill today," Turley quipped on CBS, "was enough to take the dome off its foundations."

Given the partisan warfare around the impeachment, the trial outcome is all but certain. Of more concern, however, should be the damage done to the legislative branch over the last two decades. This poisonous atmosphere of majoritarian flexing has transformed Congress from a co-equal branch to either the wingman or the executioner of the president. With this partisan war as context, succeeding House majorities will feel freer to impeach any president of the opposing party on any pretext, especially by launching constant investigations that encroach on the executive's co-equal status and automatically considering any objection to be obstructive. We will either have parliamentary systems with the executive under the thumb of the House, or presidencies entirely unencumbered by an independent legislature.

At some point, we need leadership on Capitol Hill that restores its own prerogatives while respecting the prerogatives of the executive. This would benefit both parties in the long run, and it would return the federal government to actual representative democracy. Unfortunately, after two decades in the trenches of the Democrat-Republican war, there doesn't seem to be any leaders emerging of that quality — nor a lot of demand from anyone else to produce them.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Edward Morrissey has been writing about politics since 2003 in his blog, Captain's Quarters, and now writes for HotAir.com. His columns have appeared in the Washington Post, the New York Post, The New York Sun, the Washington Times, and other newspapers. Morrissey has a daily Internet talk show on politics and culture at Hot Air. Since 2004, Morrissey has had a weekend talk radio show in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area and often fills in as a guest on Salem Radio Network's nationally-syndicated shows. He lives in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota with his wife, son and daughter-in-law, and his two granddaughters. Morrissey's new book, GOING RED, will be published by Crown Forum on April 5, 2016.