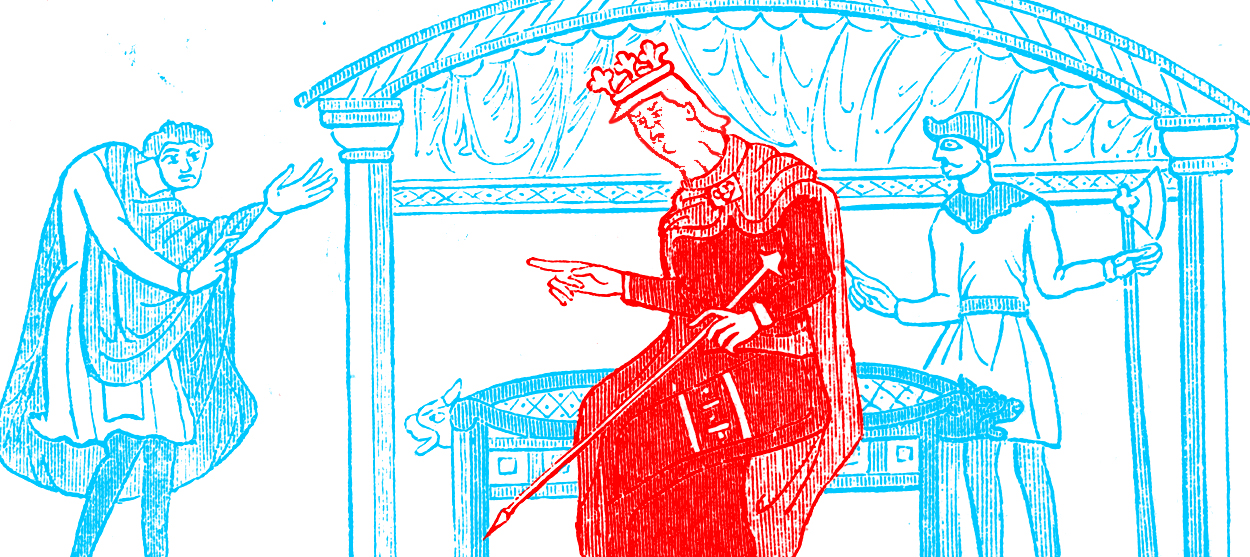

Trump is getting medieval with the states

Federalism or feudalism?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) "must understand that National Security far exceeds politics," President Trump tweeted Thursday before immediately attempting to justify his suspension of a security program for his own political ends: "New York must stop all of its unnecessary lawsuits & harrassment [sic], start cleaning itself up, and lowering taxes. Build relationships, but don't bring Fredo!"

The president here is "expanding his abuse of power to blackmailing U.S. states," accused Rep. Val Demings (D-Fla.), who was among Trump's impeachment prosecutors. "In this case, he's holding New York state hostage to try to stop investigations into his prior tax fraud."

It's not clear whether the lawsuits Trump referenced were those concerning him personally or New York State's suit over its exclusion from the "trusted traveler program." Either way, Trump, I'm certain, wouldn't see his tweet as blackmail. He referenced The Godfather, but the framework of his expectations for New York's cooperation seems a little older. Feudal, even. Trump's vision for federal-state interactions looks an awful lot like vassalage.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Western Europe in the Middle Ages organized many power relationships through the vassalage system. The details varied by time, place, and looming threat, but the basic idea was a pledged, transactional relationship between a monarch and lesser lords. The king granted his vassals authority over portions of his land and promised to provide them assurances of security. The vassals in turn would supply knights and men for their liege's army and swear to him their allegiance, or fealty.

Trump's ideas about honor and order in society are clearly medieval, as I've argued previously. Like our forebears of a millennia ago, he weighs the gravity of offenses more by the stature of the offender than the nature of the offense. As he ranks at the very top of the social hierarchy, it is all but impossible for Trump to conceive of himself as doing wrong. Allegations of his own corruption, I suspect, sincerely don't make much sense to him: Because of who he is, what he does must be right.

Seeing the states as vassals fits with that perspective quite comfortably. If Trump is king and commander-in-chief of the military, then governors, with their smaller territorial responsibility and National Guard forces, must be his vassals. Read his tweet about Cuomo in this light and it all makes sense: It's a breach of the vassal's fealty to sue the king or refuse him the tribute (in this case, driver records that could be used for immigration enforcement) he wants for his security agenda. "Uncooperative" vassals are intolerable. If there are vassals in breach of their vassalage, it can't be blackmail for the king to require them to abide by their pledge. He is but maintaining the right order of society, as he was chosen by God to do.

"I am born in a rank which recognizes no superior but God, to whom alone I am responsible for my actions; but they are so pure and honorable that I voluntarily and cheerfully render an account of them to the whole world," said Richard the Lionheart in 1193 when he was tried by the Holy Roman emperor. Richard's protests of his innocence have an eloquence Trump lacks, but the self-certain indignation is recognizable.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The trouble is Trump is not a king; it is not 1193; and to most of us — with more modern, liberal conceptions of societal order — Trump's behavior toward New York is suspect at best. That perception is reinforced by our national mythos of popular sovereignty, which survives despite two centuries of evolution of federal (and especially executive) power as well as its uncomfortable entanglement with antebellum proposals for compromise over slavery.

Our constitutional federalism — in concept, if no longer in practice — explicitly inverts the power structure of the medieval system: In feudalism, power flows from God to the king to his vassals to the populace. In the United States, power is supposed to belong to the people, and we for our convenience delegate some powers to the states, which in turn delegate some powers to the federal government. "The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people," affirms the Ninth Amendment, and the Tenth adds: "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." Power in America is supposed to flow up, not down.

It usually doesn't, of course. Movements of popular protest across the political spectrum share the complaint that those in power persistently subvert the will of the people. And federal innovations in quietly coercing state behavior with financial incentives and penalties have transformed our system into something much closer to vassalage than we might like to admit. (New York University law professors Richard A. Epstein and Mario Loyola even echo medieval language in describing this arrangement at The Atlantic: "[States'] only viable option is to accept on bended knee the sovereign's offer to return their money back, in exchange for their obedience.")

In that sense, maybe Trump is not so much a man out of his time. Maybe his monarchical dictates to New York are less a historical anachronism than an unusually indiscreet exercise of the United States' increasingly feudal federalism.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

The Week contest: AI bellyaching

The Week contest: AI bellyachingPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more

-

The best music tours to book in 2026

The best music tours to book in 2026The Week Recommends Must-see live shows to catch this year from Lily Allen to Florence + The Machine

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred