Coronavirus' lessons in limits

A pandemic is a harsh reminder that much of reality is still beyond our control

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

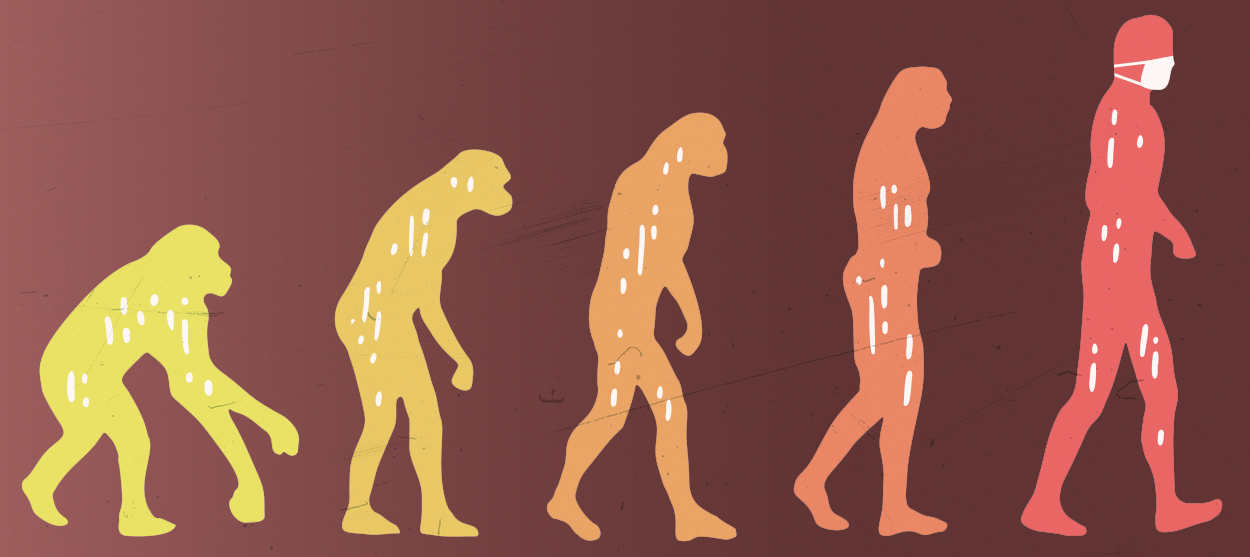

From the very beginning, the message of modernity has been one of control and mastery — over fate, over the natural world, over human nature itself. And the program for human improvement very much included the conquering of medical maladies.

It began with the hope for the expansion and dissemination of scientific knowledge that would in turn lead to economic and technological advances to make human life easier, healthier, less painful, and more peaceful, pleasant, and prosperous. Eventually, leading thinkers hoped to extend progress in knowledge to politics, allowing for the expansion of self-government and the application of expertise to the administration of a social life that was becoming ever-more dynamic and complex.

Over the past century, this effort at control has even been extended to the human mind, first in totalitarian regimes through the technological dissemination of propaganda, but more recently in the governing of liberal democracies. Less than two decades ago, an anonymous senior adviser to President George W. Bush (widely presumed to be Karl Rove) dismissed those who work (and trust) in the "reality-based community." It was now possible, this senior White House aide insisted, to create whole new realities through the manipulation of information by those in power. They could do this by controlling what we now call "the narrative." Donald Trump's constant spewing of lies and denunciations of "fake news" takes this one step further into an intentional, active, and ongoing effort to manipulate and distort the public mind of the country in order to more effectively wield political power without limits.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But that's not all. Not even close.

We now live in a world that's shot through with the pretense of mastery and control. Don't like the limits imposed by low tax rates? Just run up the deficit without consequence. Unhappy with your nose or your chin or your hairline or your breasts? Just alter them surgically. Don't like your mood? We have a pill for that. Feel uncomfortable as a man or a woman? Just change things up — under the knife and with some hormones and a dose of transgender ideology. Can't figure out how to make your start-up earn a profit? No worries: if you tell an exciting enough story, your IPO will still bring in billions as it rides the market into the stratosphere.

Want to experience the end of the world, an attack from outer space, a war to the death between superheroes, or a contagious disease that puts our simian cousins in control of the planet? We can conjure it all for you with stunning verisimilitude using CGI. Unhappy with flat notes and imperfect pop hooks? We'll make you a digitally sanitized pop hit with all the flaws airbrushed away. And we'll give you access to all of it through a miraculous machine you can hold in the palm of your hand — a device capable of transporting your mind to infinite virtual worlds of perfectly malleable hyperreality.

All of this wouldn't be so pervasive if we weren't so good at it. We have succeeded in mastering a lot — far more than the early modern champions of the goal could possibly have imagined.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But we haven't, and never will, master everything.

That's the profound and painful lesson the coronavirus pandemic looks likely to teach us. There are limits after all. The president can't just tweet out a miasma of nonsense and expect his followers will believe it forever — at least not on every subject. At a certain moment, on certain issues, when pushed to a certain point, all of us collide with an immovable object, something hard as diamonds that can't be denied or worn down or whistled past without suffering consequences that can't be outstripped. Reality proves to be recalcitrant. In particular, the reality of nature and its ultimate necessities.

Contagions spread regardless of what narratives we spin. A virus can't be explained, denied, or insulted away. Bluster and gaslighting only go so far. Yes, we can and should try to exert as much scientific control and mastery as we can. That's what public health measures are all about, and such efforts are as old as human society itself. They've obviously improved dramatically with the progress of modern medicine. If we can learn from the efforts of other countries to flatten the curve, we should do so and act on that knowledge as quickly and efficiently as possible.

But the illness will still be here. People — even famous and powerful people — are still going to get it, and some of them will die. Our parents and grandparents will still be in danger, with all of us at elevated risk. Our schools will still need to be closed and our public spaces left empty. And as long as the outcome and its ultimate toll (in lives and profit) remains unknown, the market is going to fall, wiping out trillions of dollars in wealth, with no clear sense of when the bleeding will stop. Tax cuts and bailouts and infusions of liquidity won't stop it — because we just don't know how bad things are going to get, or the cost of the measures we will have to take to prevent it from getting even worse. And because fear in the face of a potentially fatal natural process that we can't control is perfectly natural, too.

Our struggle to create a world of effortless mobility and travel for work and pleasure, of entertainment and other sensual delights, a world enveloped in safety and protection against all kinds of risks, can never succeed completely. Our powers are formidable, but they are not absolute. Because we are vulnerable creatures. Because we get sick. Because we are mortal.

All of us know this. But do we really know it? Most of the time we don't act like we do. We act, instead, like the masters of the universe we aspire to be. Our ambition and the exertions it inspires in our bodies and our minds power economic growth, great acts of creativity, and tremendous feats of invention. We've traveled to the moon and back, and put all the libraries of the world in our pockets. The achievements are wondrous.

But they can't truly work miracles or conquer nature completely.

There are limits to human efforts to impose our will upon the world and ourselves. If the pandemic staring us down helps us to relearn this sobering truth, then we will have extracted some kernel of value from the agonizing experience.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.