The Navajo Nation outbreak reveals an ugly truth behind America's coronavirus experience

One of the most important stories of the pandemic is also one of the least talked about

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In Diné Bizaad, the Navajo language, COVID-19 is fittingly called Dikos Ntsaaígíí-19, the "cough that kills." The first confirmed case in the Navajo Nation came on March 17: a 46-year-old man with a travel history, subsequently rushed to Phoenix for treatment. But then, only a few hours later, came confirmation of a second case.

The weeks that followed have been a nightmare for the Diné — the Navajo people's name for themselves — as the federal government has utterly failed to step up to the task of protecting the country's first citizens. The Navajo Nation's infection rate today is 10 times higher per capita than that of neighboring Arizona, and currently the region has the third-highest infection rate in the country outside of the epicenters of New York and New Jersey; 44 Diné have died, NBC reports, "more than in 14 other states." But the apathetic federal response to the Navajo Nation outbreak is tragically representative of a larger story unfolding in America right now, one in which the pandemic is disproportionately affecting people of color and, as a result, failing to inspire the level of urgency and horror it deserves from the public.

I'd first learned about the outsized impact of COVID-19 on the Diné in mid-March when it was reported to me anecdotally by my cousin, who works as a nurse in a coronavirus ICU in Albuquerque, New Mexico. A few weeks later, the story started to make national news; today, some 31 percent of the New Mexicans that have contracted COVID-19 are Native American, The Salt Lake Tribune reports, although it bears noting that the Navajo Nation has been more aggressive in its testing than surrounding states. While reports often blame the disease's wildfire-like spread on poverty, poor health, and lack of infrastructure in the region, the Navajo — like many other tribes — have in fact been more proactive in their approach to combating COVID-19 than most states.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

History, sadly, is a powerful teacher. "Sicknesses are not new to the Navajo people," explains the Navajo Times. There were, of course, the initial deaths in the thousands from smallpox and measles, brought by European colonists starting in the 16th century. Modern sicknesses, though, have ripped through the Navajo Nation too: The Spanish Influenza in 1918 left 2,000 Diné dead (the Navajo Times places that number higher, at 3,000 dead, or about a quarter of the nation's population at the time). In 1993, the Diné were plagued by the hantavirus outbreak, which killed 50 percent of the two dozen people it infected. Most recently, during the swine flu epidemic in 2009, NBC reports that Navajos died at a rate four to five times higher than other Americans. Naturally, as the novel coronavirus put down roots in the U.S., the Navajo Nation reached out to the government for preemptive aid was never granted.

Today's reports of the extent of the outbreak focus on the conditions of the Navajo Nation, which stretches across parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, and is home to about 150,000 people. "Native Americans are particularly susceptible to the coronavirus because they suffer from disproportionate rates of asthma, heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes," figured one recent article in CNN, adding "there's another fact that makes the coronavirus particularly menacing. Many Native Americans live in small and crowded conditions."

But while higher rates of preexisting conditions and insufficient infrastructure are certainly compounding factors, they do not tell the whole story of why coronavirus is so deadly to the Diné. The conditions of the Navajo Nation are, rather, symptoms of the historic exploitation and federal neglect of the tribes. "We didn't ask for uranium mining to destroy our communities. We didn't ask for the arsenic contamination. We didn't ask for the limitations on our economic development or the limitations on our ability to build, or our access to water. There are the real things that need to be looked at," Bijiibah Begaye, the executive director of the COVID relief group, the Tsé Ko Community Development Corporation, told the Diné Situation podcast recently. Making matters worse, communities around the Navajo Nation can be hostile to the point of open racism and terrorism against the Diné; The New York Times reports that police in Page, Arizona, recently arrested a man who allegedly "called for using 'lethal force' against Navajos because they were, in his view, '100 percent infected' with the virus."

Additionally, in a twist of particularly nasty bureaucracy, tribal nations are required to apply for grants to even be eligible for an allocation of the $8 billion of emergency coronavirus aid set aside by the government for all of Indian country (cities, counties, and states, notably, do not have to do the same). Worse still, for-profit Alaska Native corporations "were among the first in line" for shares of the relief package, Indianz.com learned this month. In response, at least six tribes are suing the Trump administration, and all of the intertribal organizations in the lower 48 banded together to slam the Department of the Interior for breaking promises, calling for the assistant secretary for Indian affairs, Tara Sweeney, to be removed from "all actions and decision-making" related to the allocation of the money. "Federal funds should not go to for-profit corporations," Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez told Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-Ariz.), as reported by Indianz.com. "Half of this $8 billion might not even go directly into tribal communities." What's left for tribes like the Navajo, unless something changes, are scraps.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The stories of exploitation and government disinterest can also be found in the tragedy unfolding in my own neighborhood of Queens, New York, where minorities are again the ones to bear the deadly brunt of the virus. Even as celebrities call COVID-19 the great equalizer, it disproportionately ravages working-class immigrant neighborhoods. The New York Times recently found that "Latinos comprise 34 percent of the deaths in New York City, the largest share for any racial or ethnic group."

Similar disparities are showing up across the country. In Chicago, Black residents make up 29 percent of the population, but 70 percent of COVID-19 deaths. In Michigan, they make up 14 percent of the population and 40 percent of deaths. Research showed that Black Americans with coronavirus symptoms across a number of states were less likely to receive a test when presenting to health care providers. Additionally, undocumented workers likely can't receive the stimulus check or unemployment money, forcing them to continue to leave the safety of quarantine for jobs; they are our country's essential workers, and our apathy is quite literally killing them. It's unsurprising that you can find the same stories in other former colonialist powers, too, like the U.K., where a study recently uncovered that over a third of critically ill patients in the country were of black or minority backgrounds. It's all connected.

It also makes watching the so-called "liberation" protests across the country — held by disgruntled, primarily white Americans who feel no immediate threat of danger to their own health, see the lockdown as overblown and inconvenient, and display a flagrant and monstrous disregard for the vulnerable members of their community — particularly upsetting. Pictures of protestors crowded against each other aren't scary simply because they're cesspools of contagious disease, but because they're a visualization of this country's racism too.

After all, it takes mighty privilege to flaunt your disregard for your neighbors. It takes murderous indifference, too.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

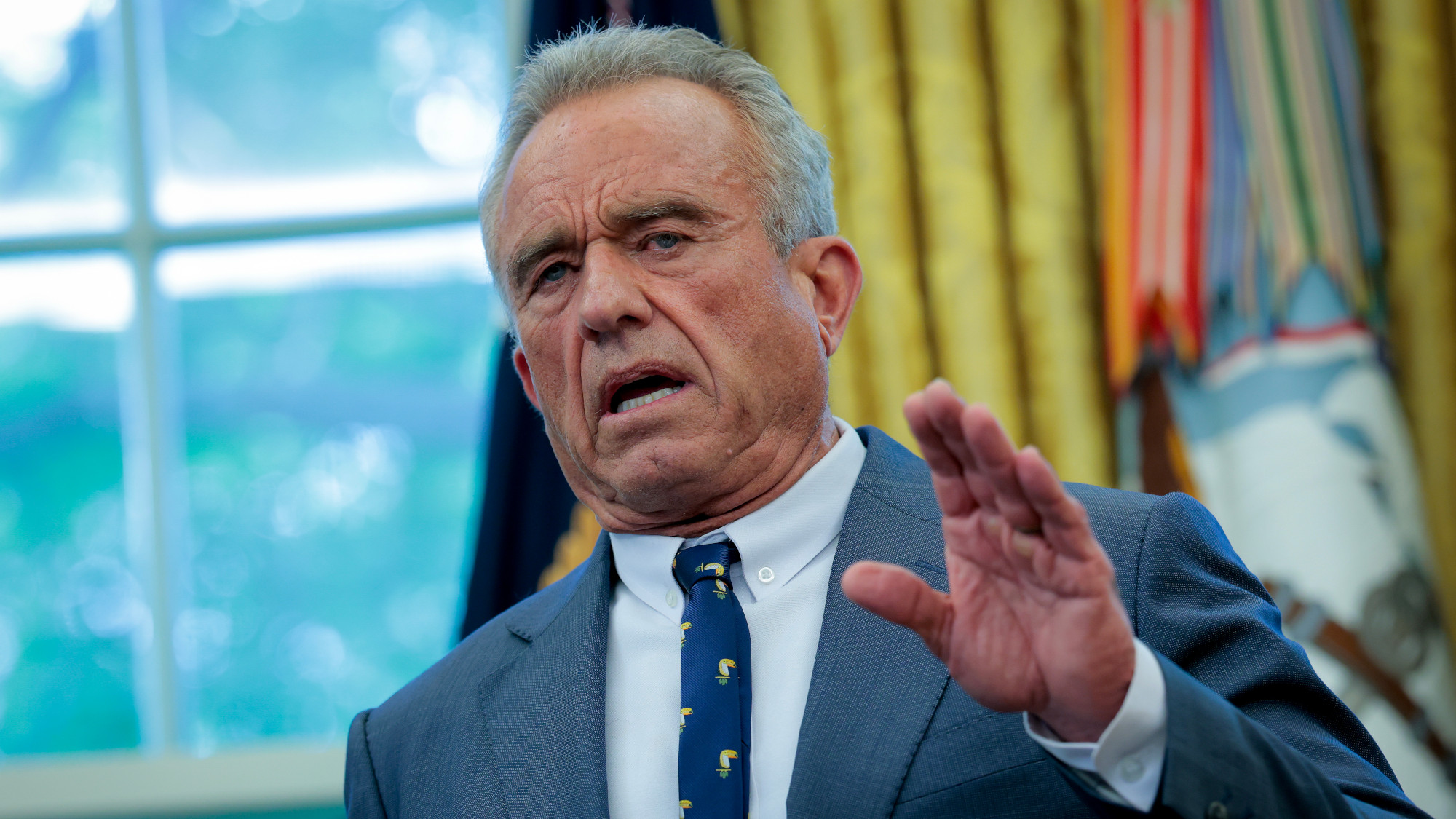

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'

-

Five years on: How Covid changed everything

Five years on: How Covid changed everythingFeature We seem to have collectively forgotten Covid’s horrors, but they have completely reshaped politics