HMPV is spreading in China but there's no need to worry

Respiratory illness is common in winter

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

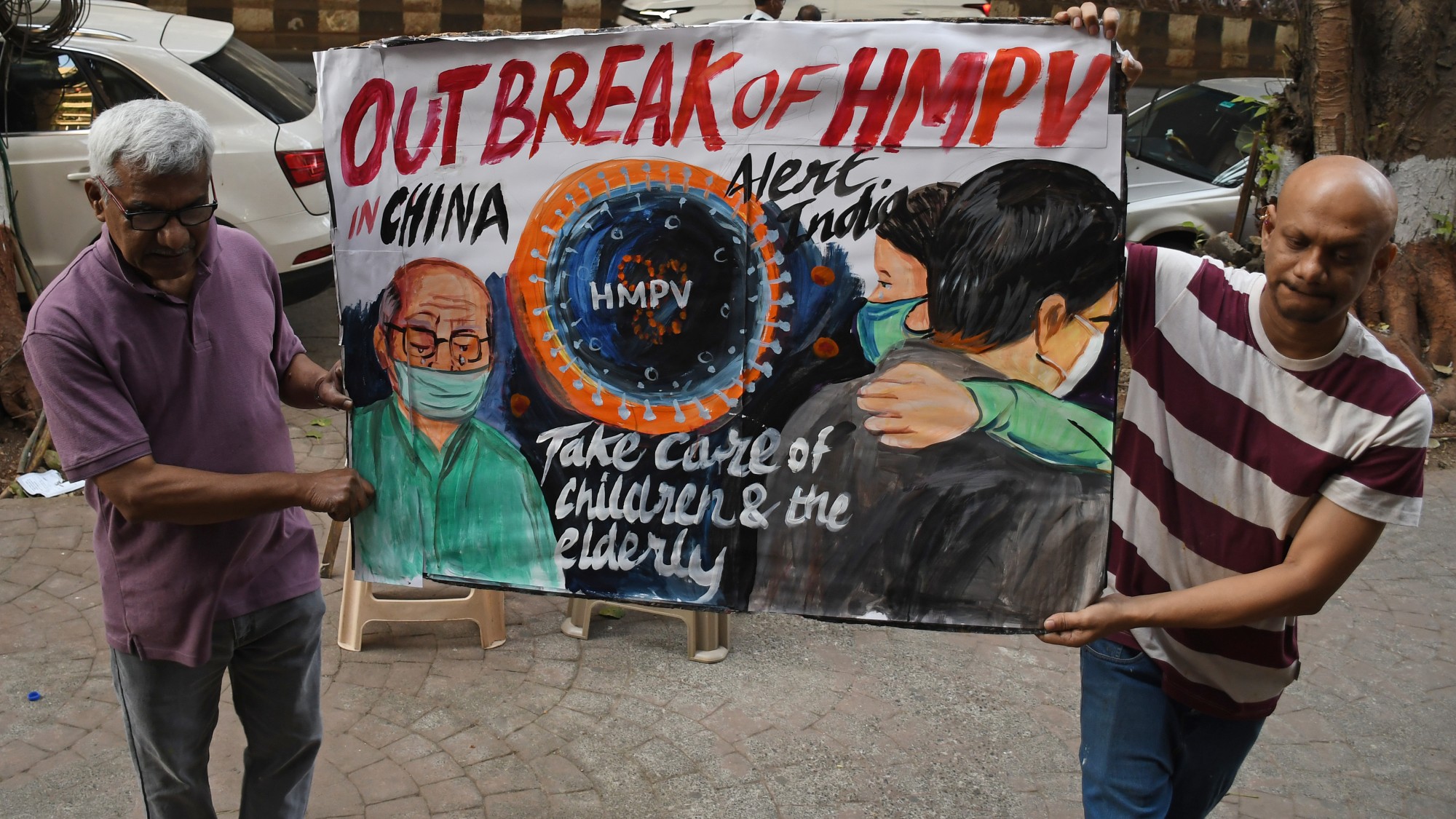

Cases of the human metapneumovirus (HMPV) are on the rise in China, causing global concern. The respiratory virus is not new, but much of the public was previously unaware of its existence. Experts say the disease is likely not going to be the next pandemic and the worry is a result of heightened wariness for respiratory illness in a post-Covid world.

What is HMPV?

HMPV is a respiratory virus that regularly circulates during cold and flu season. It is spread through coughing, sneezing and coming into contact with contaminated surfaces. It presents as common cold symptoms including cough, fever, shortness of breath and congestion. While not deadly, in some instances, cases can be more severe, especially in young children and the immunocompromised. They could "develop more severe disease where the lungs are affected, with wheezing, breathlessness and symptoms of croup," said the BBC. This could require hospitalization.

While China seems to have a spike in cases, its "reported levels of respiratory infections were along usual and expected rates, said a news briefing by the World Health Organization (WHO). The rise of HMPV is likely because "China underwent one of the world's most restrictive and prolonged lockdowns in response to Covid, reducing people's exposure to other viruses such as HMPV," said The Washington Post. "That created a situation where people became more susceptible during a surge," leading to "unusual cases even in young and middle-aged adults." The surge also aligns with low temperatures expected to last until March.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Should people be worried?

Experts aren't sounding the alarm just yet about HMPV. "It's not a new virus," Margaret Harris, a spokesperson for the WHO, said in the news briefing. "It was first identified in 2001. It's been in the human population for a long time. It is a common virus that circulates in winter and spring." The disease has been circulating similar to the flu, RSV and walking pneumonia. "How many times do you get sick in the winter and you have no idea what you've got?" said Jennifer Nuzzo, a professor of epidemiology and director of the Pandemic Center at the Brown University School of Public Health, to the Post. "It's a virus you'll get. You'll probably get it multiple times in your life."

HMPV is also not expected to be a global pandemic like Covid-19. The disease is well-studied and has been known for a long time. "There is broad population-level immunity to this virus globally; there was none, for Covid," said The New York Times. "A severe HMPV season can strain hospital capacity — particularly pediatric wards — but does not overwhelm medical centers." While there is no vaccine or antiviral for the disease, in most people it tends to pass on its own.

In general, "there's just this tendency post-Covid to treat every infectious disease anything as an emergency when it's not," Amesh Adalja, an infectious diseases physician and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, said to the Post. However, while it is not expected to grow into a deadly pandemic, HMPV "should not be ignored," said virologist Connor Bamford in an opinion for The I Paper. "We must continue research into these viruses so we can better deploy interventions like vaccines, antivirals and preventative measures for known and unknown viruses in the future."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more

-

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spot

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spotThe Week Recommends The trendy hotel recently underwent an extensive two-year revamp

-

The problem with diagnosing profound autism

The problem with diagnosing profound autismThe Explainer Experts are reconsidering the idea of autism as a spectrum, which could impact diagnoses and policy making for the condition

-

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choice

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choiceThe Explainer Is prepping during the preconception period the answer for hopeful couples?

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue Tui after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?Today's Big Question Cases are skyrocketing

-

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UK

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UKThe Explainer The ‘Victorian-era’ condition is on the rise in the UK, and experts aren’t sure why

-

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit