The wrong way to fight poverty

Democrats need to get over their obsession with tax credits

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What is to be done about poverty? For decades, the Democratic Party has advocated a strategy of refundable tax credits — "refundable" meaning that if one has no federal income tax liability, then the credit will be added to your income. (It's a silly way to obscure what is essentially a welfare program.) The most important one of these is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which pays extra income to low-income workers depending on their family structure. Expanding the EITC in various ways has been a popular policy plank for the party's leaders and presidential candidates, including Joe Biden this year.

There's just one problem: As Matt Bruenig writes in a clever new analysis for the People's Policy Project, the EITC is a policy trash fire. It does not help the poor nearly as much as conventional wisdom holds, which wasn't that much in the first place. Democrats really need to get over their fixation on this kind of policy, and embrace the social-democratic welfare state.

Here's how the EITC works. If you make a small amount of labor income during the year, it will add to that income depending on the characteristics of your household and how much money you make. For a family with two children in 2018, for instance, it added 40 cents to every dollar earned (or "phased in") up to $14,290 in income, providing a maximum credit of $5,716. But if that family made more than $18,600, the credit would be reduced (or "phased out") with each additional dollar of income, so that if they made more than $45,802, they got nothing. If you are single, or have one child, or three children, the thresholds are different in each case.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That's all very complicated, but the basic idea is fairly simple. The government adds to poor people's labor income up to a plateau, then slowly backs off the assistance again for people making more money. If you plot the EITC on a chart, it shows a series of trapezoids for each household category, which is why many have taken to using that shape as a name for this style of policy.

Democrats are smitten with trapezoids. The EITC itself was seriously boosted during the Clinton administration. During her presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton proposed making the Child Tax Credit into an EITC-style trapezoid. Rep. Ro Khanna and Senator Sherrod Brown proposed a major expansion of the EITC in 2017. Senator Kamala Harris' (D-Calif.) LIFT Act is also essentially a beefed-up EITC. Joe Biden's campaign platform would allow single workers over 65 (who are currently excluded) to claim the credit.

The pro-trapezoid argument usually goes something like this: First, the policy incentivizes work. Morally, poor people should learn the discipline of work, and practically, the EITC will increase the supply of labor and grow the economy. Second, the EITC is efficient. It has low overhead, because it is administered by the IRS which is already doing most of the relevant work anyways. Third, the EITC is well-targeted. It aims benefits at people near the poverty line, and thus provides the greatest poverty-reduction bang for the buck.

So what's the problem? As Bruenig shows, all three justifications are nonsense. First, the most recent empirical work shows that the EITC does nothing to increase the labor supply. The likely explanation is twofold. On the one hand, for most of the last 30 years, the U.S. has been well short of true full employment. EITC recipients are generally the last people to be hired; inducements for them to find jobs will not work if there are not enough jobs available. On the other hand, the EITC is so complicated and obscure that a great many recipients have no idea it even exists, or how exactly the eligibility schedules work — indeed, only 78 percent of people who are eligible for the credit actually claim it, and many of those probably don't know it. More than half of EITC claimers use a professional tax preparer, which will usually give them a big refund without any indication where it came from (or bury it in fine print). One cannot be incentivized into work if one doesn't even realize it is happening.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That leads directly into the second problem. It's true that the IRS is quite efficient, but this fails to consider the cost of private tax preparation. One survey found that tax prep companies — which cluster in low-income communities because poor people are more likely to need help, in part because these very companies have successfully lobbied Congress to make claiming the EITC pointlessly complicated — suck up between 13 and 22 percent of EITC benefits. Taking the midpoint of those as a decent estimate and multiplying it by the 60 percent of EITC claimers who use a tax prep service produces a total overhead of 11.0 percent — which is over 18 times greater than Social Security. More than a tenth of the EITC is an utterly unjustifiable subsidy of predatory tax prep firms.

Third, the EITC has a timing problem. Your benefits are calculated based on last year's income, but you receive the benefits this year. Poor people's income bounces around a lot, and lots of folks end up receiving a credit they would not be eligible for under their actual current income, or don't receive one they would be eligible for. Yet for poverty-measurement purposes, previous analyses of the EITC have applied the credit to the prior year's income. (That is, if the 2018 credit boosted your income over the 2018 poverty line, you are counted as being pulled out of poverty even though you didn't receive the money until 2019.)

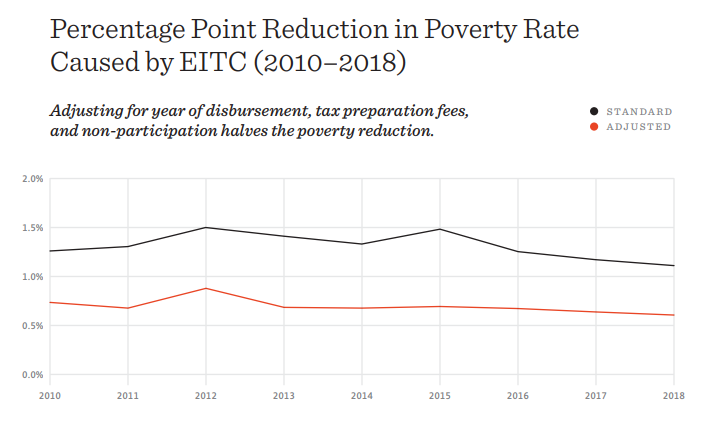

Taken together, Bruenig finds that all three of these problems reduce the number of people the EITC pulls out of poverty by a whopping 47 percent. A mere 0.7 percent of the population are dragged over the poverty line thanks to the credit:

(Courtesy People's Policy Project)

So, by the standards advanced by its supporters, the EITC is a monumental policy faceplant — it does not increase labor supply, it is hideously inefficient, and its benefits are poorly-targeted. But even that is not the end of the problems. The EITC is also an effective subsidy of low-wage employers, because it allows companies to pay less than they otherwise would have to. Some research indicates that up to 72 percent of EITC spending is captured by employers in this way, depending on the local labor market conditions.

Perhaps worst of all, the phase-in structure of the EITC deliberately leaves out the very poor. Even the 0.7 percent figure above overstates the actual poverty-fighting work done by the credit, because benefits are focused on people who are fairly close to the poverty line (however inaccurately). The very poorest people who have no labor income — that is, the people who need help the most — get no EITC at all. The deeper problem with trying to "target" benefits to get the greatest possible reduction in the count of people who are in poverty is that doing so is gaming the metric. By contrast, a program that pulled every single poor American up to one dollar short of the poverty line would not reduce headcount poverty at all, while eliminating it in practice.

If we compare the American model of fighting poverty to the kind of classic social-democratic welfare state practiced in Northern Europe, the Nordic countries win in a rout. But to come around to the Nordic style, Democrats must get over the capitalist ethics which have had a hammerlock on the thinking of both parties for decades. By this view, poverty is an individual virtue problem — poor people are assumed to be lazy and irresponsible, and unconditional welfare programs can only lure them into the "hammock" of dependency, as Paul Ryan calls it. Therefore, the government should force people into jobs so they can learn the dignity of a paycheck (and, not coincidentally, make profits for business owners). The idea of handing money to people who aren't working makes even many committed liberals blanch.

But as an empirical matter, poverty is overwhelmingly a problem of lifecycle and incapacitation. Over three-quarters of poor people are either children, students, disabled, or elderly — that is, people who largely cannot or should not work, which is about half the population. It simply is not true that most poverty is caused by lack of virtue. It is caused by the fact that capitalist institutions only distribute income to wealth owners and workers — which is why the Nordic countries have benefit programs for each category of non-worker. Indeed, even in this benighted country the really significant poverty reductions are done with universal benefits like Social Security pensions and disability insurance.

In sum, trapezoids are hell's own policy shape, and they must be burned with fire. Let's stop fussing with these preposterous phase-in schedules, and start handing out money.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern history

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern historyin depth The taking of Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is the latest in a long string of high-profile kidnappings

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred