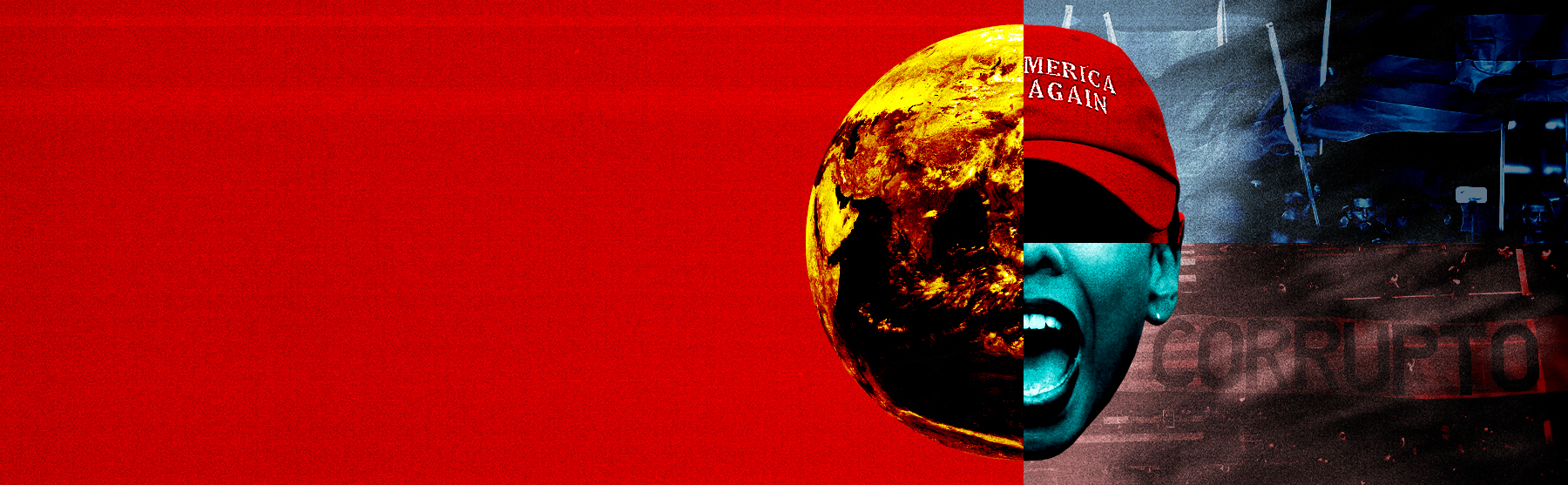

The hidden world war

We thought the internet would pave the way for peaceful collaboration. How naïve we were.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, intellectuals throughout the West began to hope that the longstanding liberal ideal of the "open society" could be applied to the whole world, with nations everywhere embracing free trade, porous borders, and the easy movement of people and capital.

Advances in technology — especially improvements in communication and the transmission of information — would be a big part of this process of ever-increasing openness. The overriding assumption at the time was that the more we talked to one another, and the more we built and used digital networks to facilitate interaction across our differences, the more we would come to note and appreciate our similarities. The internet would make this possible, giving birth to a world of peaceful collaboration in the pursuit of knowledge and mutual understanding, with a future of fully globalized homogeneity within our reach.

How naïve such hopes seem to us now.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Doubts first arose with the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the American-led wars that followed, and the financial crisis that started in 2008 and wreaked economic havoc across much of the world over the next few years. But what really shattered the dream were the twin earthquakes of 2016 — the Brexit vote in Great Britain and the election of Donald Trump in the United States.

It seemed to many like the march toward increasing openness had been halted and maybe even reversed. Borders and walls were rising once again. Rancorous conflicts over fundamental questions of morality and identity were polarizing politics within nations, while international alliances, rules, and trade agreements were being torn up or tested in new ways. The electoral potency of right-wing populists in countries across the world, from Latin America and Europe to South and East Asia, along with the stresses and strains of a global pandemic, have only added to the sense that the march toward a more globalized world has been turned back in favor of a future of resurgent nationalism, conflict, and difference.

But this counternarrative is at best only partially accurate. The recent shocks to both the international system and liberal expectations for the future haven't turned back globalization entirely. They have revealed, instead, that the technological advances that were once considered a gateway to a more homogeneous world actually encourage and foster the creation of new, potent forms of crossnational solidarity and political conflict.

We can observe the power of social media platforms to do the work of forging solidarity in the United States, where people separated by vast distances across the American heartland have joined together in virtual space to support candidates of the populist right, including Donald Trump. A similar process is taking place in countries around the world, wherever right-wing populists hold or seriously vie for power. That's because their primary base of support is usually found far from densely populated city centers, dispersed across the countryside. By making it possible for people living in these mostly rural areas to link up with far-flung likeminded compatriots, the internet is contributing in a decisive way to galvanizing anti-establishment movements around the world.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the trend isn't just found within individual nations. It's also spreading across borders.

We sometimes saw viral behavior prior to the digital age, spread by newspapers and then radio and television. Revolutions roiled a series of European countries in 1848. Student protests encircled the world during the summer of 1968. Dissidents taking to the streets to demonstrate against one authoritarian government often spawned copycat protests in other autocratic countries during the so-called "Third Wave" of democratization that stretched from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s. Information about an event in one place can catalyze another event somewhere else — political scientists call this a demonstration effect.

Today's internet-fueled demonstration effects happen on a much larger scale and at a much more rapid velocity than ever before.

The American-focused far-right QAnon conspiracy theory has spread to countries around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, France, Italy, Brazil, and Finland. Even more widespread have been kindred protests against COVID-19 restrictions, and especially mask mandates, in dozens of nations. Trump has even found expressions of support for his efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election on the streets of Tokyo.

But the internationalization of political and cultural conflict isn't exclusively a phenomenon of the right. This past spring and summer, the wave of left-leaning protests and riots that spread across the U.S. in the aftermath of George Floyd's death at the hands of a white police officer in Minneapolis quickly sparked parallel Black Lives Matters demonstrations in every region of the world — from France and Great Britain to Kazakhstan, Sri Lanka, and South Korea. Sometimes those protests focused on news from the U.S., but more often they transferred energy and indignation from those events to local incidents of injustice. The rainbow flag has likewise become a symbol of gay and transgender rights the world over, its meaning recognized by everyone on every side of the issue in every country on the planet.

Thanks to the flood of information and images flowing ceaselessly into the incredibly powerful compact computers we carry around with us everywhere we go, political and cultural identities, affinities, and animosities are now constantly being forged and activated on a global basis. Humanity is uniting and dividing in new ways that transcend national borders. Many American Trump supporters would likely feel greater solidarity with fellow right-wing populists in Brazil, Russia, and Hungary than they would with progressives in their own country — just as many of those protesting for racial or gender equality and justice around the globe probably feel closer in spirit to each other than they do with hardline conservatives living close by in the real world.

As sociologist Robert Wuthnow has shown, Americans have already experienced a version of this process in the religious sphere of life. Where once Roman Catholics, Jews, and Protestants of different denominations viewed each other as rivals and even threats, in the decades since World War II, ideological attachments and aversions have come to the fore, replacing theological and doctrinal differences. Now conservatives in each of these denominations feel greater kinship with each other than they do with liberals in their own congregations — and the liberals feel the same about the conservatives.

As ideological distinctions have come to take precedence over other differences, American politics has become increasingly polarized — and American culture increasingly politicized. What will the world be like if the same process unfolds on a global scale — with national and other local forms of solidarity giving way to ideologically rooted and technologically energized attachments and aversions that transcend countries, regions, religions, and languages?

It would be a world at once coming apart and coming together in unstable new ways — a world in the process of being transformed by globalization, but not in the manner so many of us once hoped to see. The homogeneity, the smoothing out of deep differences, we expected to accompany the dissolving of borders and other barriers would be stillborn. In its place, we would get heterogeneity — new forms of conflict, modeled, perhaps, on the increasingly all-encompassing American culture war that our wondrous devices and apps broadcast instantaneously across the planet, inspiring people everywhere to take sides on intractable moral disputes.

This virtual world war, with populists and progressives on every continent engaged in pitched battle online and in real-world elections over nothing less than the moral tenor of global civilization, could easily provoke actual warfare within or between nations. But the deepest fault lines would transcend borders and countries — with each side making a case for its own vision of how the world should be ordered, and drawing support from and taking aim at enemies next door as well as on the other side of the globe.

I don't know where this heterogeneous globalization will end up. But I suspect we're going to find out.

This is the second article of a two-part series on technology and populist politics. Part one can be found here.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred