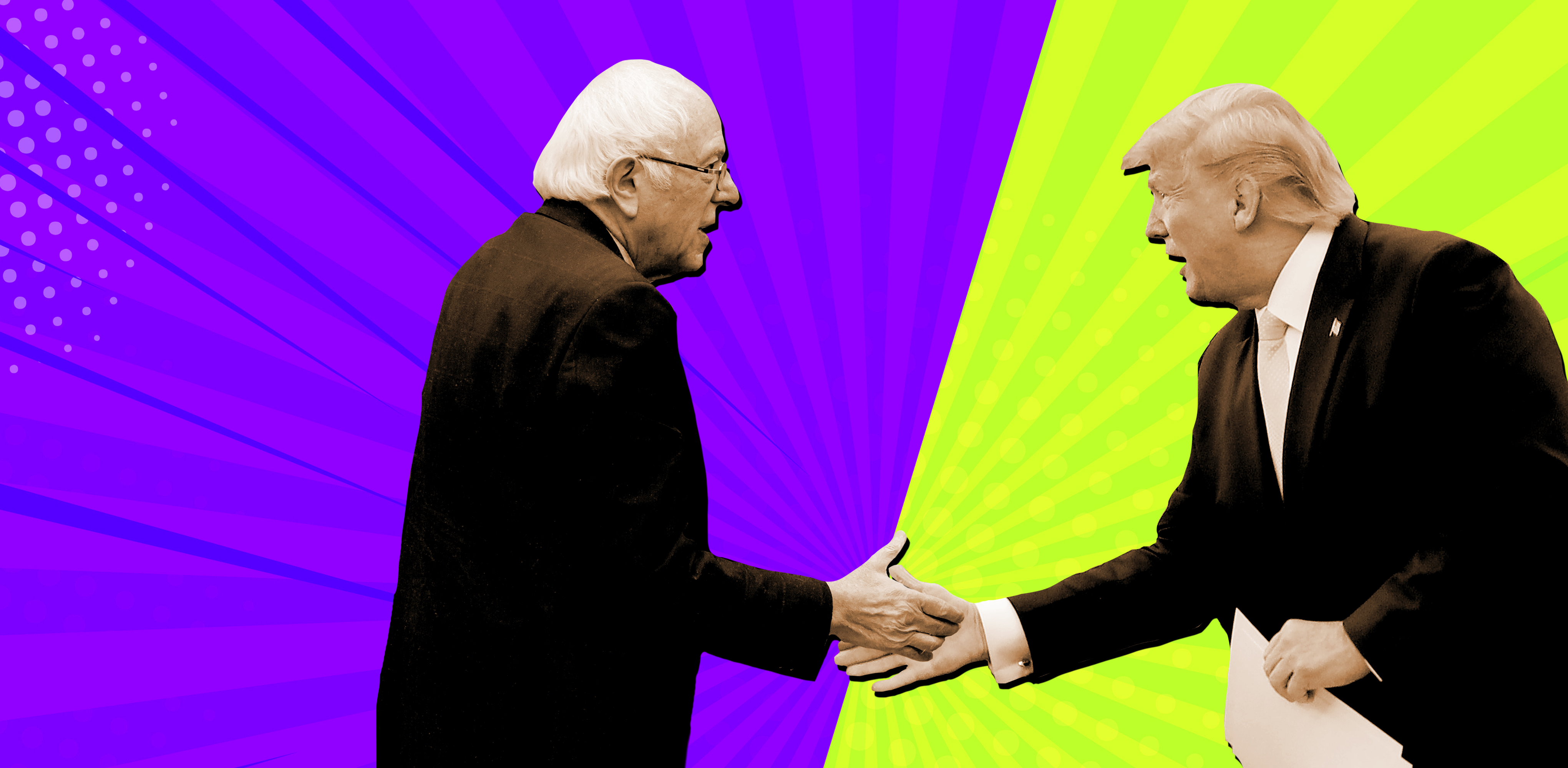

The Trump-Bernie alliance that could have been

It's the great 'what if' of the Trump presidency

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For this moment, anyway, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) might be President Trump's greatest ally in Congress.

Sanders announced on Monday that he will filibuster the Senate's anticipated vote to override Trump's veto of the defense funding bill until and unless Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) stops his obstruction and lets the chamber vote on Trump's demand for $2,000 pandemic stimulus payments to most Americans.

"McConnell and the Senate want to expedite the override vote and I understand that," Sanders told Politico. "But I'm not going to allow that to happen unless there is a vote, no matter how long that takes, on the $2,000 direct payment."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Sanders might be more likely to get his vote than to actually procure Senate approval for the $2,000 checks — though Sens. David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler, both Georgia Republicans in tight runoff elections, said Tuesday morning they'll vote for the payments, as did Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.). But this very temporary alliance between Sanders and Trump represents a taste of what might've been, a throwback to when both men's insurgent presidential campaigns were full of populist potential.

For a few months in early 2016, Sanders and Trump seemed almost mirror universe versions of each other.

Each man was a relative outsider to the party establishments. Both railed about how those establishments had left working-class Americans behind, and both were openly suspicious of international free trade agreements they said exported jobs overseas. Both were less-than-sanguine about immigration's effects on workers. Yes, Sanders labeled himself a democratic socialist and Trump presented himself as the epitome of capitalist success, but their rhetoric overlapped considerably. Fortune even offered a quiz daring readers to tell the difference between the two men's public statements.

There was never much crossover between the two men's supporters — a March 2016 poll showed just 13 percent of Sanders voters had a favorable view of Trump — though the MAGA-ites and Bernie Bros both gained reputations for snarling and elbow-throwing. That didn't stop Trump from making a bid for those voters when Sanders faded in that year's primary campaign against Hillary Clinton.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Bernie Sanders had a message that's interesting," Trump told MSNBC in April of that year. "I'm going to be taking a lot of the things Bernie said and using them."

Trump was mostly trolling, trying to drive a wedge between Sanders voters and Clinton, the Democratic nominee. But Trumpist populism was always pretty much a pose — early in his term, he bullied some manufacturers into announcing they would keep their jobs in America, it is true. But those efforts didn't always pay off as promised, and in any case the president found populism more useful as a political tool, a way to generate the rage of his supporters and rail against the elites who despised him, rather than the lodestar for an actual governing agenda. His most significant legislative accomplishment is the passage of a giant tax cut whose benefits mostly went to the rich and big corporations — and mostly failed to create good new jobs, as Trump and his allies had promised.

Sanders, meanwhile, returned to the Senate (and the presidential campaign trail) and started working for "Medicare for all." And by the time 2020 rolled around, Trump — rhetorically at least — no longer found Sanders' message "interesting." Instead, he spent his campaign railing somewhat ironically against socialism, and trying unsuccessfully to pin Sanders' views on decidedly centrist Joe Biden. These days, the two men could hardly be further apart in their politics and rhetoric.

The fight over $2,000 payments, though, is a glimpse of what was possible if Trump had had a genuine interest in or ability to advance populist legislation, instead of using populism as a button to push in order to get a reaction. He might have found common ground with Sanders on issues here and there to advance the interests of the working class. If he had done so — even in the face of opposition from his own party — we might be talking very differently now about Trump's presidency. At the very least, such an effort would have been more interesting than the tedious grind of culture warring that has dominated the last four years. Some ambitious Republicans seem ready to pick up the mantle of economic populism. How might Trump have fared if he had pushed hard for such policies from the beginning, instead of waiting until the waning weeks of a lame-duck presidency?

We'll never know. Instead, Trump is going home in a few weeks. And Sanders remains in Washington, still working and fighting.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Mamdani vows big changes as New York’s new mayor

Mamdani vows big changes as New York’s new mayorSpeed Read

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The anger fueling the Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez barnstorming tour

The anger fueling the Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez barnstorming tourTalking Points The duo is drawing big anti-Trump crowds in red states