America's overreaction syndrome

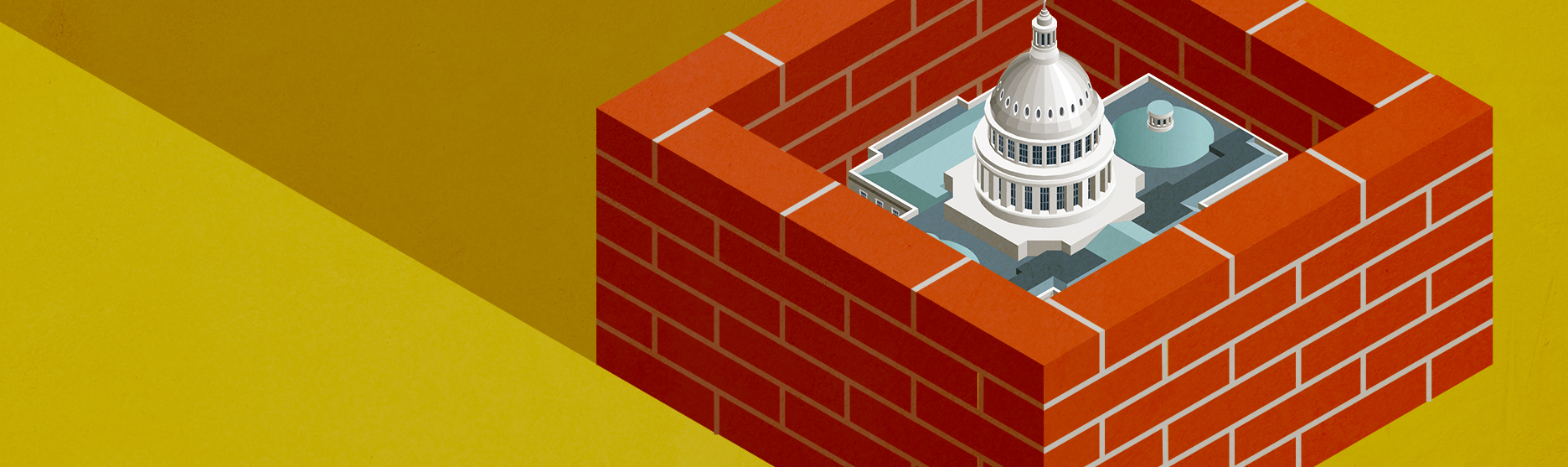

Why installing "permanent fencing" around the Capitol would be a terrible — and predictable — mistake

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The events of Jan. 6, 2021 — a president using a series of lies to incite a violent insurrection against Congress as it was attempting to certify the results of a free and fair presidential election — were a very big deal. This includes the failure of security measures on Capitol Hill to protect the building and its occupants from the attack. All of it calls out for a serious response. Precisely what that response should be is a matter for democratic deliberation and debate, informed by input from experts as part of a thorough investigation.

But you know what is not a serious response? A proposal, made last week by the acting chief of the U.S. Capitol Police, Yogananda Pittman, to install "permanent fencing" around the Capitol building, along with "back-up forces" stationed nearby.

The reaction of lawmakers from both parties, as well as that of Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser, was quite negative. So maybe the core institution of American democracy won't end up looking like a remote, imperial outpost in need of permanent physical protection from an angry, oppressed citizenry, which is exactly what would happen if the building housing the national legislature were permanently ringed by protective fencing with police or soldiers ready to strike insurgents at a moment's notice.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yet the sad fact is that this is exactly the kind of response one might expect from the government of the United States, which has a record by now of wild and irrational overreaction to getting caught with its pants down. Recognizing this unfortunate tendency is the first step toward preventing it from happening again.

The trend began with the 9/11 attacks, which traumatized the country, exposing our vulnerability to external enemies with a vividness that left many genuinely shaken. For much of our history, Americans have felt protected from the worst of the world's problems both by the stability of our democratic institutions and by our physical distance from powerful rivals abroad. But Al Qaeda's attack showed in spectacular and deadly fashion that stateless opponents on the other side of the planet could hit and hurt us badly.

The attacks cried out for a decisive response — and the military campaign to break up terrorist training camps in Afghanistan and capture or kill Osama bin Laden was it. Yet nearly 20 years after American troops first arrived in the country, and close to 10 years after they finally killed bin Laden, we remain there, terrified that if we withdraw, the threat will return to do us harm again.

And then there is Iraq — the second majority-Muslim country that we invaded and occupied in response to the 9/11 attacks. The case for overthrowing the government of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was not really based on any hard evidence of a link between him and the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon, because such a link didn't exist. It was based on a strategic calculation: In a world of recently exposed American vulnerability, we couldn't countenance allowing a sworn enemy of the United States to remain in power. We needed to demonstrate our toughness.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the response to 9/11 was not limited to exertions of military force abroad. The fact that terrorists were able to hijack multiple airplanes with weaponry no more formidable than box cutters they easily smuggled on board led to massive changes in airport security. Now lines at checkpoints were vastly longer and slower. Whole new scanners were developed and deployed at airports around the country to ensure that the events of that September morning would never be repeated.

And in the most bizarre development of all, Americans would forevermore be required to remove their footwear while crossing through airport security because a single terrorist three months after 9/11 managed to smuggle a (defective) bomb onto a flight in his shoe.

The point in highlighting these responses to 9/11 is not to mock all or even most of the people who enacted these policies or implemented these changes. Those in positions of responsibility for public safety during and following disastrous events carry a heavy burden that should lead us to judge them with at least a modicum of empathy.

But that doesn't mean we should suspend critical scrutiny entirely. The fact is that from foreign policy to the full range of airport security implemented by the Transportation Security Administration in the months and years following 9/11 — not to mention massive new programs of clandestine domestic surveillance — public officials responded to the U.S. failures on that day by embracing an effort above all to appear to be taking the threat of future attack with utmost seriousness.

Appearances were the point.

Those in positions of public responsibility on 9/11 looked really bad. They didn't see the hit coming. So in response, they wanted to look tough. Serious. Decisive. The result was a foreign policy of muscle flexing and throwing little countries against the wall to show we mean business. And airport safety designed to be a form of security theater. Henceforth we would be made to stand in interminable lines and submit to annoying and pointless rules prior to being allowed to fly because this would make it look like we were taking the threat of terrorism much more seriously than we were prior to 9/11.

When we look like we're being tough, serious, and decisive, we feel safe — and those in charge of keeping us safe thereby insulate themselves from criticism that they weren't taking the threat seriously before the original bad event took place. "Just look at how thoroughly we're doing our jobs now!"

With memories of the events of Jan. 6 still fresh in our minds, we seem poised to do the same thing again: respond to a traumatic event by making a largely symbolic statement intended to show just how seriously we — and especially the people who dropped the ball so badly on the day of the melee — are taking the threat of future insurrectionary violence.

This would be a terrible mistake. Symbols — appearances — are undeniably important in politics. But for that very reason, we should be wary of the symbolism of making the U.S. Capitol look like an armed encampment protecting itself against a siege by our own citizens. That would be civically appalling, projecting an image of a country embattled and buckling, its leading institutions needing to protect themselves behind battlements, with the threat of political violence rising up just beyond them. It's hard to imagine a symbol that would do more to project an image of a republic in decline, tottering on the verge of a much darker form of politics.

It would also be a massive overreaction to a threat of future violence that should be containable in much less dramatic and invasive ways. Which isn't to say those ways are easy. Yes, there probably needs to be more of a defensive infrastructure built on and around Capitol Hill, largely out of sight, and those in charge of it need to do their jobs with much greater vigilance than the U.S. Capitol Police showed on Jan. 6. But the real, essential, arduous work must happen elsewhere, within the Republican Party, and within our political culture more broadly. The insurrectionists and those who incited them need to be confronted and decisively defeated politically.

If that proves impossible, the country will face a much graver threat than an afternoon of mayhem in the halls of Congress.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.