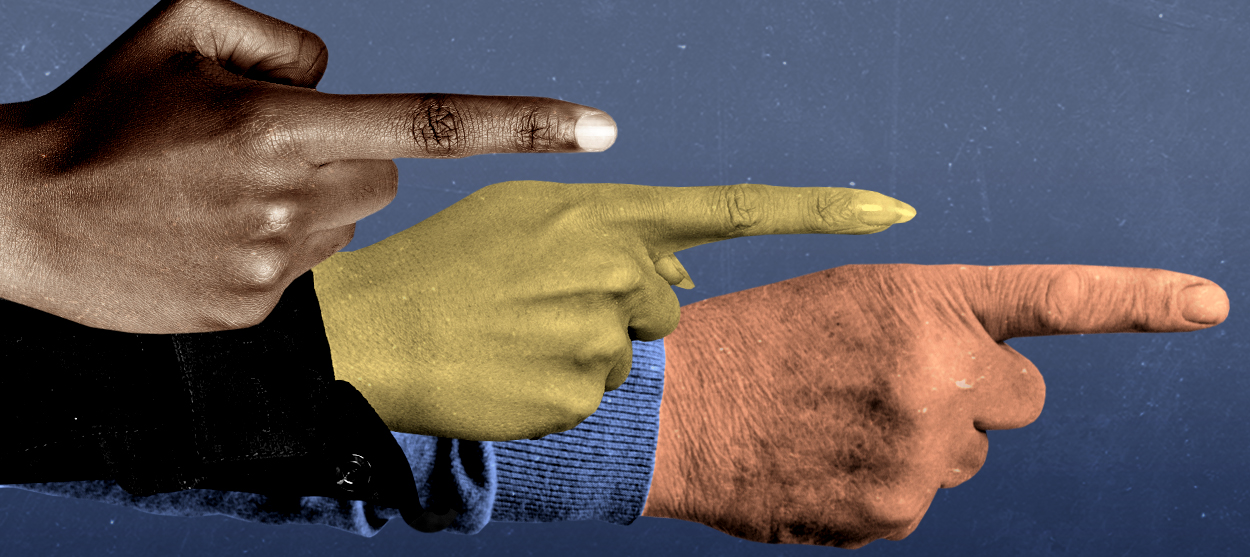

The pandemic blame game

What I learned from my son's COVID-19 diagnosis

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You can tell a lot about a person by whom or what they blame when bad things happen.

A white man kills eight people (six of them Asian American women) at three massage parlors in the Atlanta area. A Muslim man kills ten people, seemingly at random, at a grocery store in Boulder, Colorado.

When you hear these stories, do you blame the individual perpetrator? The gun he used in his act of violence? The Constitution for giving him a right to possess it? His race, gender, religion, or some other category or group to which he belongs? American society for failing to recognize and treat his mental illness?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Questions like these have been on my mind a lot this week. That's partly because the recent shootings in Georgia and Colorado each ignited furious debates about who or what deserves blame. But the deeper reason why I've been pondering such questions is that after a solid year of pandemic-related worry, frustration, anger, claustrophobia, and relative good health for me and my family, this week my 18-year-old son got sick with COVID-19.

When it comes to the world-historical epidemiological events of the past year, some Americans (mostly Republicans) blame China for allowing the virus to spread around the world. Others (mostly Democrats) blame Donald Trump — calling the performance of his administration inept and holding it responsible for making the pandemic far worse than it needed to be.

Many in this latter group of liberals and progressives seem pretty sanguine about the virus itself. Not that they are happy about it. But they accept that deadly contagions are a fact of life and that their rapid spread around the globe may be an unavoidable negative externality of an open world that is also responsible for a multitude of economic, cultural, and social benefits. Restrictions are necessary to contain the virus, with the imposition of temporary lockdowns when new cases spike, mask-wearing in indoor public spaces treated as given, and other public-health measures treated seriously, very much including the universal taking of vaccines when they become available. The blame here tends to focus on those who resist or reject these rules and expectations, including the refusal to abide by lockdowns, wear masks, and take vaccines.

Those in the former group — libertarian-leaning conservatives in the U.S. and abroad — are less willing to adjust their behavior to mitigate the spread of the virus. They tend to be quick to blame overzealous government officials, elected and appointed, and those cheering them on, for making an unfortunate situation far worse. This group will blame China for allowing the virus to arise and then to escape its own borders, but beyond that they are much more willing to let the disease run its course, convinced that the sacrifices of freedom in trying to quash it are simply too great, especially when those efforts so often appear to make relatively little difference to the outcome at the macro level.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In this dispute, as in so much else, I am a centrist. Our family has been pretty vigilant in abiding by public-health restrictions. My wife and I both have medical conditions that place us in high-risk categories, and we don't want to contribute to the spread of the contagion. On top of that, we're both fortunate to have jobs that are compatible with working from home. So we have. We mask up to go grocery shopping once a week. In the warm months last summer and fall we went out to eat on occasion, seated outdoors. We go for walks around the neighborhood unmasked, making an effort to stay distanced from anyone we encounter on the street. But other than that, we've mostly hunkered down and waited for the virus to abate — and more recently for the vaccines to get distributed.

But our willingness to shut down the lives of those we love has not been limitless.

Our son started college last fall and struggled badly with remote learning and isolation in a single dorm room, so we decided that it made sense for him to take a leave from school this spring. But would we force him to spend months on end languishing in our house with time stopped — no purpose or socializing for him at all? After a few weeks of thinking about it, we made a decision: We would let him take a job delivering pizzas a couple of days a week, a task that could be done with relatively little indoor contact with others, and we would allow him to get together socially with two high school friends on weekends.

This was a risk — one that worked out fine for nearly four months. But now, a little over a week since my wife and I received our first vaccine doses, our luck has run out.

Our son returned from a sleepover last Friday night with these friends to tell us that one of the two had woken up Saturday feeling sick. Sunday morning we learned this friend had tested positive. Our son became symptomatic on Monday. That evening he briefly emerged from quarantine in his room to get tested. We received the positive result Wednesday morning. The rest of the family is quarantining in the house until all of us get tested early next week. With any luck, our son will be able to emerge from isolation in his room at the end of next week, assuming his fever is gone by then.

Who's to blame for bringing the virus into our household? My wife and I — for allowing any socializing at all? Our son — for pushing to do it and maybe not being as cautious as he could have been when outside the house? Our son's friend — for possibly being irresponsible in his other social contacts? Trump and Joe Biden — for not doing more to distribute vaccines faster so the pandemic could be over by now?

Part of me is inclined to blame everything, including myself.

But how much sense does this really make? The pandemic happened. We've done a lot in response. Some actions are pretty miraculous (like developing vaccines in record time). Others are much less heroic but nonetheless prudent changes in behavior to slow the spread and hopefully spare ourselves, our loved ones, and our fellow citizens. Still other measures are probably foolish overreactions or outright mistakes that do little good or even make things worse overall. All of it takes place under conditions of uncertainty.

Given the limits of our knowledge, it's remarkable how much human beings have managed to conquer chance and master nature (including the spread of deadly pathogens). But those achievements are still limited. That's because we remain vulnerable, embodied creatures. We get sick. We can die of disease and accidents — and we assuredly will die eventually of something. It's reasonable to do many things to prevent the worst outcomes, but it isn't reasonable to do everything to prevent them — because doing so is bound to prove futile in the long run anyway, and in the meantime such efforts can make life less worth living.

Do I wish we'd made our son stay in the house since he returned home from college before Thanksgiving? No. And I don't think this would change if he were sicker, or even if our 15-year-old daughter or my wife or I got very sick and suffered greatly. I mean, sure, if any of us ended up on a respirator fighting for our very lives, I'd probably be plagued by all sorts of regrets. But those would be the thoughts and feelings of a man flinching in the face of the most terrifying and wrenching of experiences. It wouldn't be me at my best. It would be me longing impotently for a do-over — wishing in a childish way that I could have known months ago what can only become clear in the actual unfolding of time, which is that our good fortune would only last so long.

Life involves weighing and balancing competing, conflictual goods, and making trade-offs among them on the basis of what seems reasonable at the moment. When the calculus doesn't work out as we anticipated and hoped, that doesn't necessarily mean anyone or anything deserves to be held culpable for inflicting the harm.

All it means is that bad things can and do happen in life, and sometimes there's no one to blame. Accepting this reality might not be much of a consolation, but it does feel something like the beginning of wisdom.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.