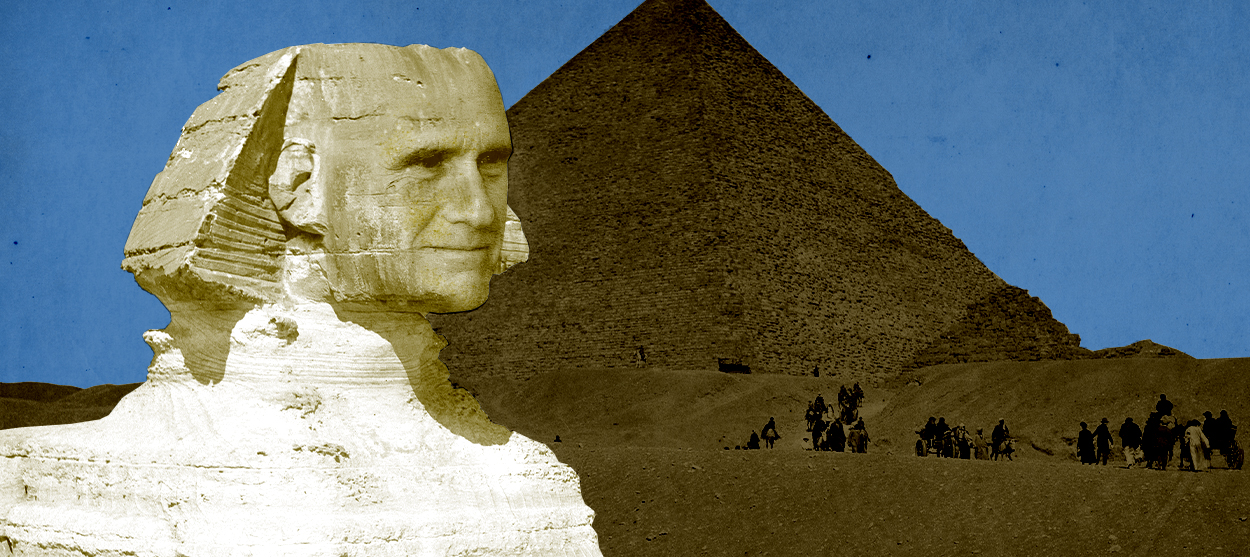

Mitt Romney, Republican sphinx

Why the Utah senator keeps defying characterization

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Mitt Romney has always been something of a sphinx. That was true during his 2012 presidential run when he was forever coming off as a kind of right-wing text-to-speech program. And it's true today, as he has emerged as the populist ideas man in the GOP Senate when only months ago he was the nation's premier Never Trump Republican.

This whipsawing has many on the right asking again: Who is Mitt Romney?

Throughout the Trump years, Romney was known as that rare Republican who was willing to badmouth the president. He never hid his contempt for Trump, voting to impeach him not just once but again for good measure, and was the only Republican senator to do so the first time around.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

More than once that summoned the wrath of MAGA Twitter onto Romney's head. He was frequently assailed as a counterfeit conservative and a sad memento of a political consensus gone-by. The Trump creation myth goes something like this: prior to 2016, progressive Democrats and globalist Republicans did little except back-slap each other into scoliosis at Georgetown cocktail parties, while the country screamed and burned. Then Trump rose over the Potomac like the sun, stunning and befuddling the old guard. Among those confused and passé establishmentarians was Romney.

Further evidence of this was to be found in his hawkish foreign policy views. Among the many Republican shibboleths that Trump smashed was the Bush Doctrine, which held that America had an obligation to spread democracy around the world and especially throughout the Middle East. Trump complained (correctly) that these adventures had accomplished little for American interests. Yet Romney continued to party like it was 2004. He assailed plans to pull American troops out of Syria, Afghanistan, even Germany.

He's still doing that today, as it happens. Yet something else has changed, something that's led many conservatives to take a fresh look at Romney. Republican politics has once again been scrambled. Trump's Twitter account has been silenced. The world has moved on. The Trump loyalty test still matters but less than it used to. The main question that now confronts the right is how to best preserve conservative values under a hostile administration.

The nature of those values has also shifted, courtesy of those heady years under Trump. Before 2016, conservatism had usually meant the Reagan-era three-legged stool: traditional values, small government, and national security. Today, at least among some right-of-center intellectuals, it's focused not so much on ideology as constituency. It cares less about shrinking the federal state per se than about wielding it to avail the working class, which it credits with swinging the balance to Trump four years ago and views as a countervailing force against decadent liberal elites.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And here, Romney has suddenly emerged as a one-man think tank. He's working on a plan to raise the minimum wage. He released a bill to reduce student loan debt and make college more affordable. He's echoed Trump by saying Washington needs to pass a major infrastructure package. He's proposed a monthly child allowance to help families. These used to be liberal priorities, but today they're winning Romney plaudits from some of the pro-Trump intellectuals who once dismissed him as yesterday's man.

So again, that question: Who is Mitt Romney? Is he Trumpism without Trump? An opportunist trying to make amends after his impeachment votes? The heir to the Rockefeller Republicans? A protocol droid who keeps getting hacked from different directions?

Perhaps a little of each. But there's another strand in there too that's worth mentioning. It dates back to Romney's term as governor of Massachusetts when he decided to work with Democrats on statewide universal health care. "Romney was intrigued with it because of the personal responsibility aspects," Jonathan Gruber, a professor at MIT who assisted with the effort, told the Boston Globe. To Romney, requiring people to purchase health insurance wasn't an onerous government mandate so much as a way for individuals to take charge of themselves and stop free-riding off of the state.

The resulting law, RomneyCare, a government program ostensibly in the service of conservative ends, does more to explain Mitt Romney than anything else. The man is neither a libertarian nor a nationalist; he's a compassionate conservative in the mold of George W. Bush. He believes ardently in personal responsibility, competitive markets, family values. But he also believes that government, so long as it's manned by virtuous statesmen, can be a partner in these efforts rather than a zero-sum adversary. The state can help do good within certain fiscal and constitutional limits, whether on behalf of single mothers struggling to pay hospital bills or Afghanis trembling before the Taliban.

This strain has a long history on the right. Now it's surfaced again among the Trumpists, though grounded in notions of class and nation rather than self-reliance and noblesse oblige. Romney is where the old guard and the new thinking meet. The question now is whether voters are onboard for another round of big-government idealism.

Matt Purple is a senior editor at The American Conservative. He's also a contributor to the Spectator USA and has written for National Review, Reason, The National Interest, and many others. A native of Connecticut, he lives in Alexandria, Virginia, with his wife and son.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred