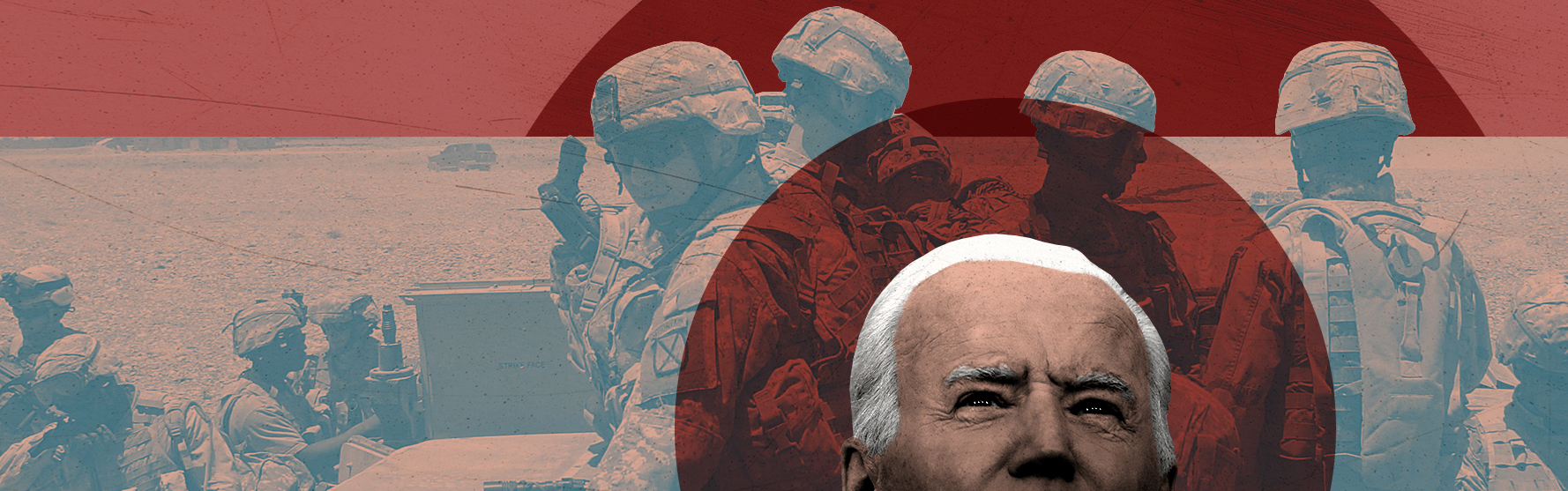

Biden says the Afghan war is ending. That increasingly looks like a lie.

Contractors, air strikes, trainings, and clandestine operatives, oh my

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President Biden's April speech announcing his plan to end the 20-year U.S. war in Afghanistan was frank and pragmatic. "We cannot continue the cycle of extending or expanding our military presence in Afghanistan, hoping to create ideal conditions for the withdrawal, and expecting a different result," he said. Though Washington's diplomatic and humanitarian work in Afghanistan will continue, "we will not stay involved in Afghanistan militarily," Biden pledged. Now is the "time to end America's longest war," he said. "It's time for American troops to come home."

That's true. But it also increasingly looks like a lie.

Let's the review the evidence. Exhibit A: Biden did not say he will end the U.S. air war in Afghanistan, and there's no reason to believe he has any plans to do so.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Trump administration dramatically escalated this campaign, causing record civilian casualties with a record number of bombs. The Biden administration has made clear in recent days it will maintain airstrikes in Afghanistan even without a traditional ground presence, following a pattern we've previously seen in Somalia, Syria, Libya, Yemen, and elsewhere.

In fact, The New York Times reported last week, a few days after Biden's withdrawal plan officially launched, the United States conducted half a dozen airstrikes, and "Afghan ground commanders [asked] for more help from American warplanes." Whatever Biden claims, this is warfare. Here's how you know: If another country did an airstrike on your town, what would you call it?

Let's turn to Exhibit B: Airstrikes aren't the only sort of military involvement that will carry on after the war "ends" in September. Though regular ground troops will largely leave, we'll still have a significant presence of "clandestine Special Operations forces, Pentagon contractors, and covert intelligence operatives."

Contractors are currently hiring for hundreds of new positions in Afghanistan, New York magazine reported Wednesday, and though some U.S. contractors already there will be subject to the September deadline, many will not. That's significant because contractors far outnumber the forces Biden will withdraw. There are about 3,300 troops he's promised to pull by September but around 16,000 contractors employed by the Defense Department alone, more than 6,000 of them American. Other agencies like the State Department and the CIA also have contractors, though their numbers aren't often publicized, and these workers outside the Pentagon aegis aren't subject to DoD withdrawal plans. It's likely that thousands of these technically-not-troops will remain in Afghanistan come fall. "I don't have much to share because no one has told us sh--," one such contractor told New York. "If there is an endgame, no one has told it to us."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That brings us to Exhibit C: All this ongoing military involvement requires bases — only not in Afghanistan, because the war is "over." Thus the Pentagon is presently scoping out options from "nearby countries to more distant Arab Gulf emirates and Navy ships at sea." It's the foreign policy version of when you're on the playground and you've been told to stop poking Jennifer in the eye, so instead you follow her around waving your hands in her face, yelling, "I'm not touching you! I'm not touching you!"

Soon, the Pentagon will not be touching Afghanistan, just flapping its arms all over the greater Middle East. "We will look at all the countries in the region, our diplomats will reach out, and we'll talk about places where we could base those resources," Marine Corps Gen. Frank McKenzie, head of U.S. Central Command, said in a Senate hearing last month. "Some of them may be very far away, and then there would be a significant bill for those types of resources because you'd have to cycle a lot of [aircraft] in and out" to keep the strikes and surveillance going. Never fear, he added: "That is all doable." We can keep bombing.

Our last exhibit comes from Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley, who indicated in a press briefing last week that U.S. military training of Afghan forces may also continue after the September withdrawal. "It's possible," he said, the training will simply move to a different country. "We will remain partners with the Afghan government and with the Afghan military," said Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin at the same briefing — so perhaps we will end up doing nearly the same thing we've been doing, only with higher transport costs.

Altogether, this does not comport with what Biden told the nation in his speech last month. It goes well beyond the nimble, targeted counterterrorism operations his address envisioned. It's not an end to "involve[ment] in Afghanistan militarily." It's not bringing every American soldier home.

Biden says our longest war is ending, but by any normal understanding of the words, it's not.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

The 9 best steroid-free players who should be in the Baseball Hall of Fame

The 9 best steroid-free players who should be in the Baseball Hall of Famein depth These athletes’ exploits were both real and spectacular

-

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What to watch on TV this February

What to watch on TV this Februarythe week recommends An animated lawyers show, a post-apocalyptic family reunion and a revival of an early aughts comedy classic

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military