What the critics are saying about Tracey Emin/Edvard Munch at the Royal Academy

Seeing their work side by side, it is clear that the artists share ‘a depth of turmoil that can leave you breathless’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

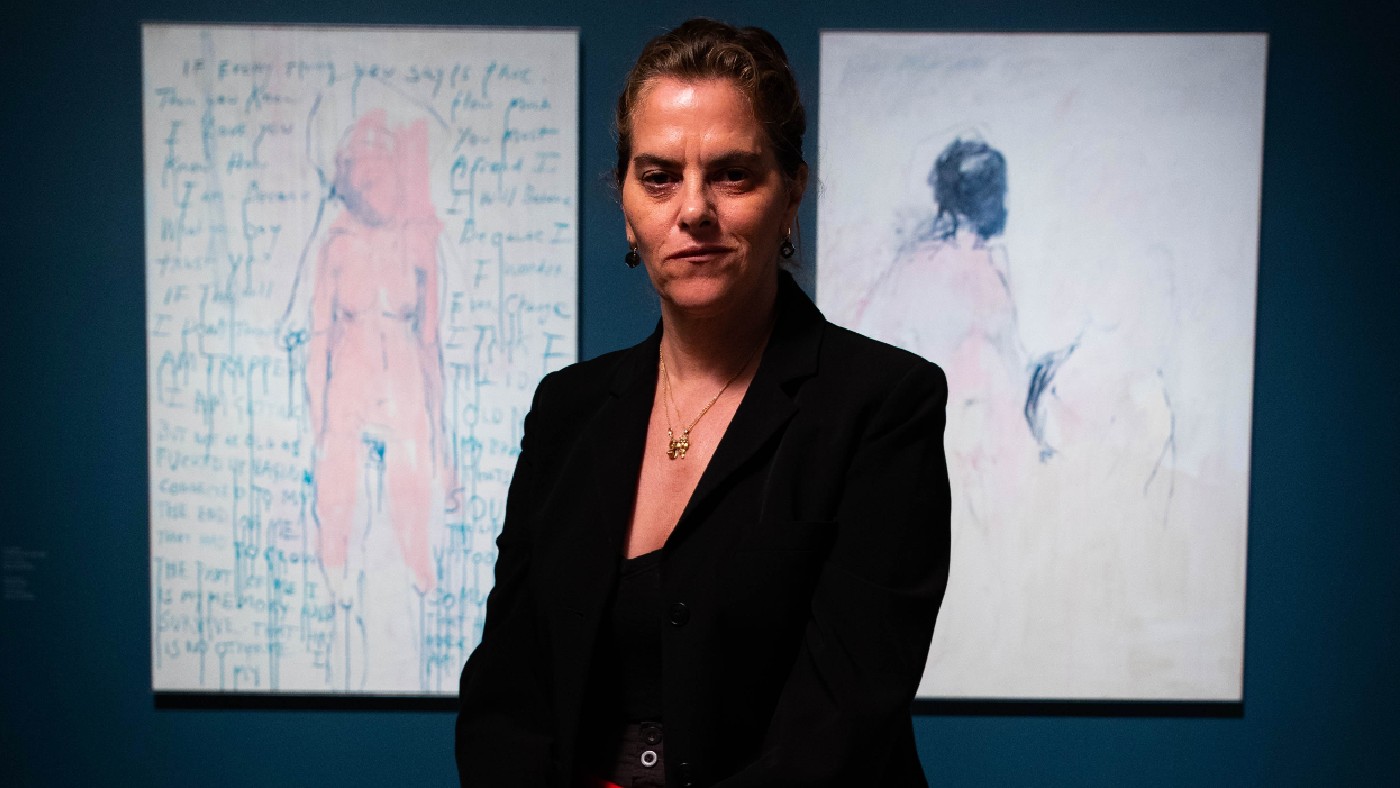

The old critical maxim that you should “look at the work, not the life” never made much sense with Tracey Emin, said Tim Adams in The Observer. Her uncompromisingly confessional work has always explored her life “in messy close-up”, exposing “body and soul” for all the world to see. And her work is as “visceral” as ever in this long-delayed exhibition, which pairs her art with that of her hero, Edvard Munch.

When Emin was assembling the show – called The Loneliness of the Soul – she had genuine reason to believe it might be her last. In June 2020, she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of bladder cancer that required “radical surgery”. As she listed with “typical courageous candour”, she had “her bladder, her uterus, her fallopian tubes, her ovaries, her lymph nodes, part of her colon, her urethra and part of her vagina removed”.

Emin, thankfully, has now made a full recovery, yet the spectre of impending death haunts every corner of this triumphant exhibition. Bringing together more than 25 of her works, including paintings, neons and sculptures alongside 18 oils and watercolours by Munch, the display demonstrates how the Norwegian artist’s anxiety-ridden imagery has informed Emin’s practice since her student days: both have placed a sense of loneliness and anguish at the heart of their art. Beyond this, however, the exhibition brings “everything that Emin has made and felt and suffered in the past” to “full expression”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Although Emin’s contributions to the show actually predate her diagnosis, it’s hard not to view them “through the prism of her illness”, said Alastair Sooke in the Daily Telegraph. The “no-holds-barred canvases” here are characterised by “crimson rivulets and dark ominous clots”, “writhing, coupling, pain-stricken bodies” and “a frenzy of thrashing drips and lines”. They are the artistic equivalents of “an anguished howl reverberating across a wasteland”.

Her selection of Munch’s art, meanwhile, is “immaculate”: a wall of ten “intimate, incandescent” watercolours of female models Munch painted towards the end of his life is “tinged with a wistful, detached eroticism”. An oil painting of a nude depicts its subject “with bright red hands, as though freshly dipped in gore”; and Women in Hospital (1897) “dwells on the ageing female body” – a daring subject for its time.

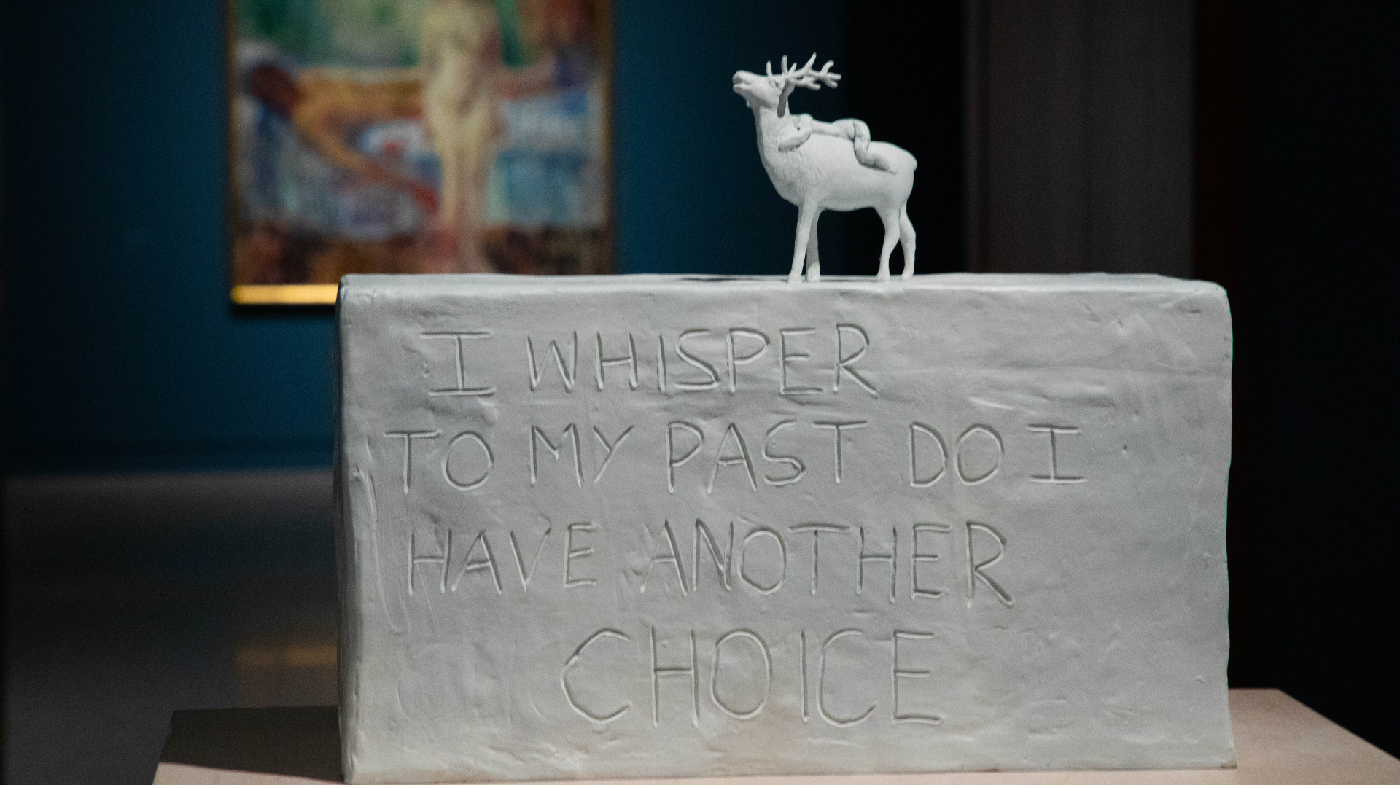

There are disappointments, however: Emin’s sculptures here represent “a misstep”, while a 1998 neon spelling out the words “My c*** is wet with fear” is an unnecessary evocation of her “YBA glory days”. Emin describes Munch as a “kindred spirit”, said Nancy Durrant in the London Evening Standard. Small wonder: seeing their work side by side, it is clear that the artists share “a rawness, an honesty and a depth of turmoil that can leave you breathless”.

Munch’s “painterly influence”, too, is often explicit: Emin’s 2018 canvas I came here For you, for instance, feels like a deliberate “echo” of her forebear’s Model by the Wicker Chair (1919-21). It is all deeply moving–and in Emin’s case, “often distressingly intimate”. Indeed, if there’s one complaint, it’s that “the sheer heart-stopping clamour of her paintings is almost too much for Munch’s quieter anguish”. There is “something magnificent about that, but my God, it’s a lot”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Royal Academy, London W1 (royalacademy.org.uk). Until 1 August

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriors

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriorsThe Week Recommends British Museum show offers a ‘scintillating journey’ through ‘a world of gore, power and artistic beauty’

-

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brand

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brandThe Week Recommends The electric SUV promises a ‘great balance between ride comfort and driving fun’