Exhibition of the week: Eileen Agar’s Angel of Anarchy

The work of Paul Nash, Lee Miller and Salvador Dalí’s contemporary is being explored at the Whitechapel Gallery

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sooner or later, the art world “was always going to remember Eileen Agar”, said Waldemar Januszczak in The Sunday Times. An artistic contemporary of Paul Nash, Lee Miller and Salvador Dalí, Agar (1899-1991) was a true original. Possessed of “tons of talent” – as well as “good looks” and “an address book to kill for” – she was an indomitably independent artist who lived an “action-packed life” which took her from Argentina to the South of France to Cornwall. Along the way, she created a wealth of eccentric and often dazzlingly memorable art, jumping from “style to style” and “mood to mood” as she pleased.

Although generally associated with surrealism – she was one of the few women featured in the landmark 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London – she was far too much of a “free spirit” to really fit in with any movement. Perhaps as a result, Agar never received the recognition given to many of her peers. As this sprawling new exhibition demonstrates, her comparative obscurity is unmerited. The show brings together more than 150 paintings, photographs, collages and sculptures, from every stage of her career, to finally give this relentlessly inventive artist her due.

Born to a wealthy Scottish father and an American mother, in Buenos Aires, Agar was a true cosmopolitan, said Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. She befriended the likes of Picasso and Ezra Pound, and had a long relationship with the surrealist poet Paul Éluard. Yet there is something distinctly British about her work, particularly evident in her collages and sculptures of the 1930s. Two prevailing themes were her love of the seaside, and a novel understanding of “the power of found stuff”: in the course of the show, we see coral and shellfish “arranged in dreamlike boxes”, “small sculptures made of shells and pebbles”, and black and white photographs of “shells, rocks and driftwood”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Her most famous work, Angel of Anarchy (1936-40), is an eerie plaster head covered in “silk scarves, sea shells and giraffe hide”; while Marine Object (1939) lodges an array of “fantastical flotsam” within the broken neck of a Roman amphora. It is just as beguiling as surrealism, but shorn of the psychoanalytical “baggage” so beloved of the movement’s continental practitioners. Alas, the brilliance of this phase of Agar’s career did not filter into her later work. The show traces her art right up to her death, and gets ever duller as it grinds to its conclusion. To describe it as anticlimactic would be putting it mildly.

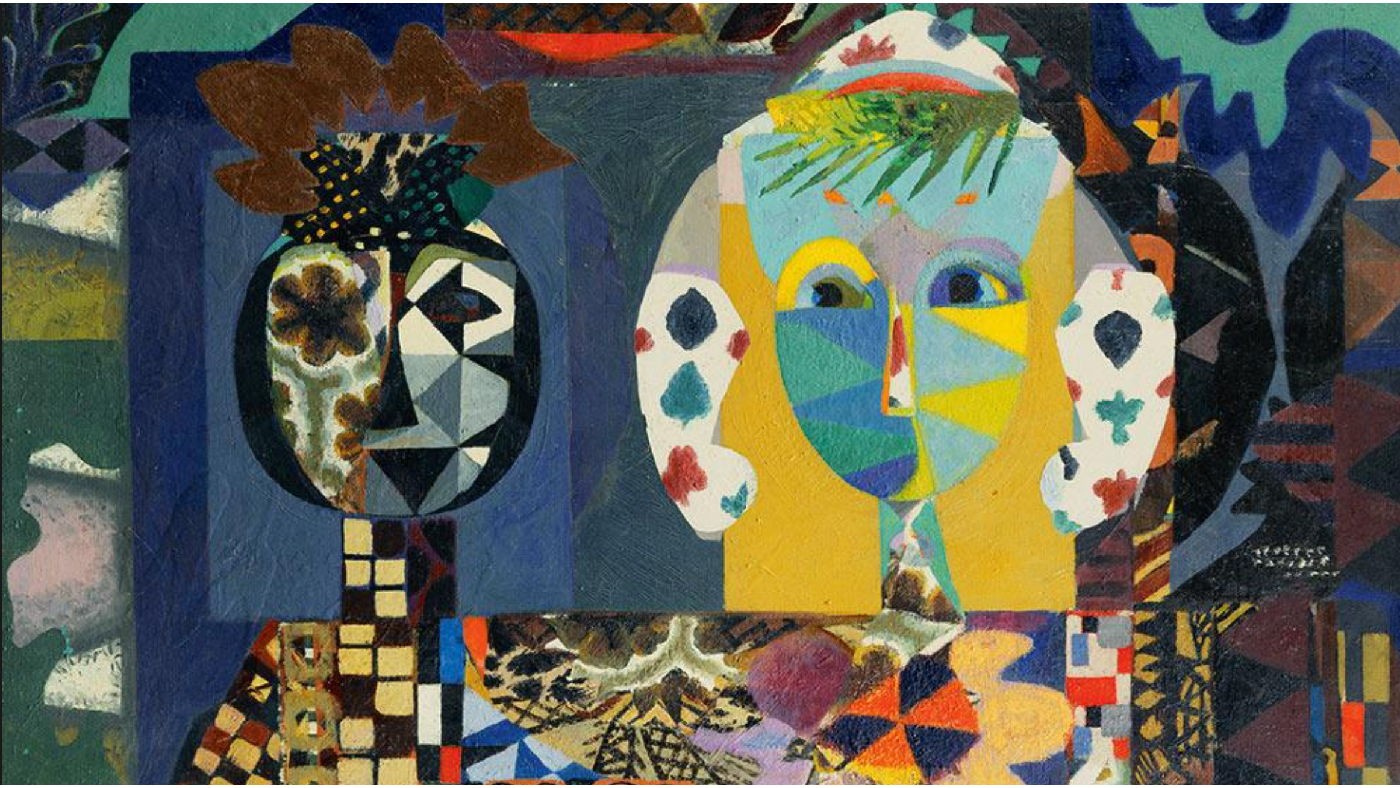

Some of the work on show is less than “remarkable”, said Cal Revely-Calder in The Daily Telegraph. But Agar’s later career should not be written off: the semi-abstract 1961 painting Lewis Carroll with Alice is deeply “unsettling”; similarly notable is 1978’s Collective Unconscious, a “largish acrylic canvas” teeming with “geometric and organic forms”.

She rarely attempted to disguise her many influences: while one 1935 self-portrait owes a debt to Jean Cocteau, The Bird’s Nest (1969) borrows shamelessly from Matisse. Yet her work was never less than distinctive, and Agar’s individuality is manifest in everything here, from a photo of some buttock-shaped rocks in Brittany to a 1936 Pathé newsreel in which she walks around London wearing a hat covered in fake seafood, much to the astonishment of passers-by. This is not a show without its ups and downs, but it is a fine celebration of a “vivacious” – and sometimes “masterful” – artist.

Whitechapel Gallery, London E1 (whitechapelgallery.org). Until 29 August

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com