Exhibition of the week: The Making of Rodin

For all its strengths, the show is let down by a needlessly ‘censorious’ attitude towards its subject

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

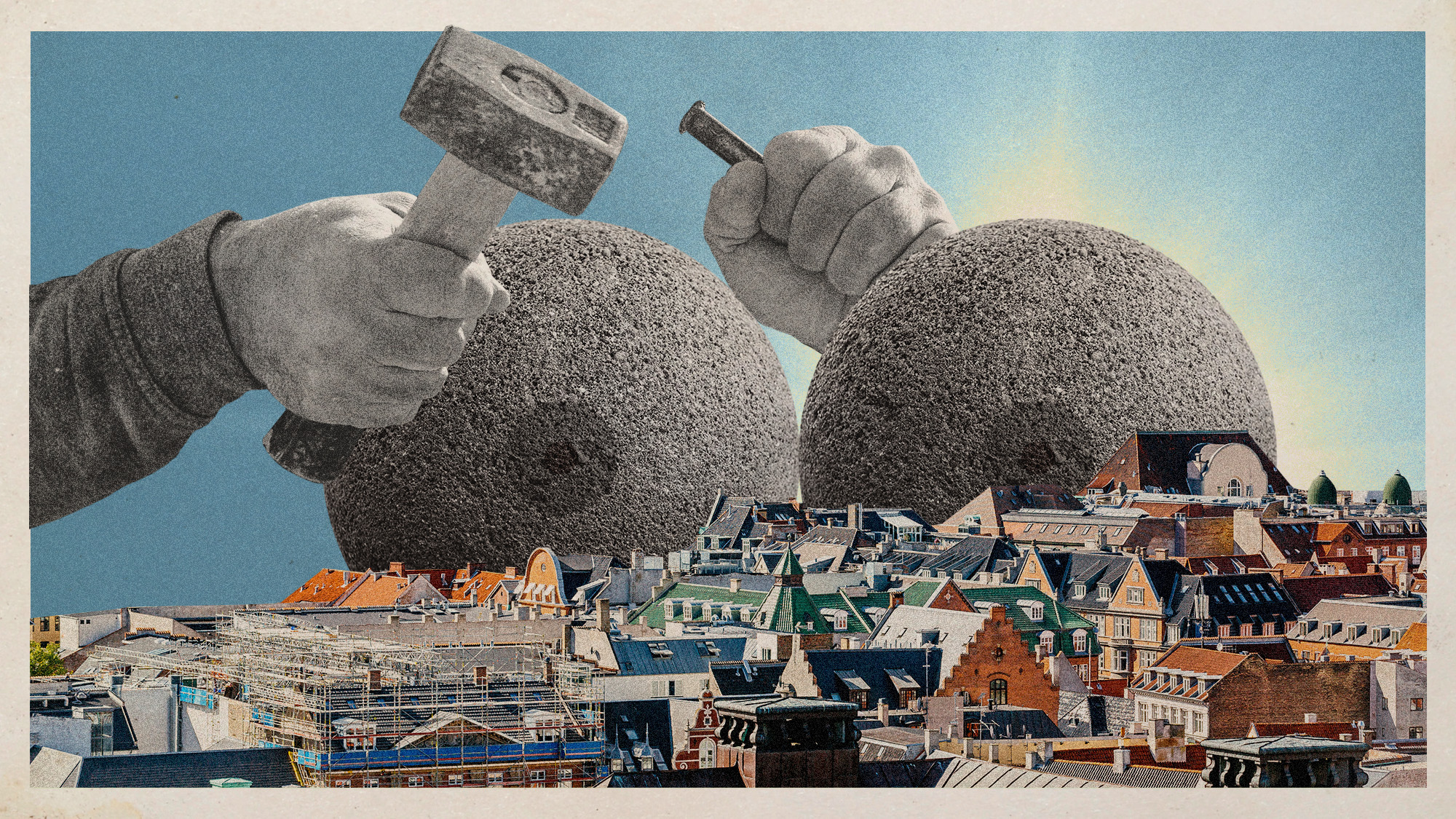

In 1899, Auguste Rodin mounted a “decidedly unconventional” exhibition in Paris, said Rachel Campbell-Johnston in The Times. Rodin (1840-1917) took the decision to show his works in plaster, a material hitherto considered only as a “transitional” part of the process by which a sculpture progressed from the drawing board to its finished state in bronze or marble. The artist aimed both to “emphasise the fundamental role” that plaster played in the development of his “audacious modern vision”, and to “mythologise himself as a solitary genius”; because unlike bronze cast, a work in plaster would bear the imprint of his hand. The resulting show was “a muddle of figures and fragments and maquettes”, evoking the atmosphere of the artist’s studio. It would, the curators of a new exhibition at Tate Modern argue, set the pace for sculpture in the 20th century.

In its first exhibition to open since lockdown restrictions were relaxed, the museum sets out to replicate the thrill of Rodin’s groundbreaking display, bringing together more than 200 works, mostly in plaster. The Making of Rodin includes many of his most famous sculptures and reminds us that he was unquestionably “the most innovative sculptor” of his time.

In many ways, this is a “serious and accomplished” exhibition, said Alastair Sooke in The Daily Telegraph. It features a roll-call of Rodin’s “greatest hits”: several plaster versions of The Thinker (1881) and a marble of his immortal The Kiss (1901-04) are present and correct, as are less-celebrated gems such as The Age of Bronze (1876-77), an “astonishingly supple likeness of a young Belgian soldier”. Yet for all its strengths, the show is let down by a needlessly “censorious” attitude towards its subject. The curators make the mistake of judging the artist by our contemporary mores. It tells Rodin off for “appropriating” classical sculpture, which he collected. A series of “frankly erotic” studies of naked women is accompanied by a caption informing us that the relationship between artist and model was “starkly unequal”. Such “finger-wagging” is pointless and irritating: “if you don’t like the work, don’t show it”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Any attempt to engage with the exhibition’s arguments is “futile”, said Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. The curators make a series of pretentious and historically illiterate claims about Rodin’s supposed “modernity”, repeatedly insisting that “the factory-like system he employed of churning out plaster models and bronze casts” made him a direct precursor to 20th century artists like Andy Warhol or Jeff Koons. In fact, this was common practice for many 19th century sculptors. The show offers precious little in the way of “biographical context” or iconographic analysis, and consequently risks misrepresenting Rodin’s art.

Yet enjoyed as a “purely aesthetic” experience, it is a pleasure from start to finish. Among the highlights are a full-scale plaster cast of The Burghers of Calais (1889), Rodin’s unforgettable monument to a group of 14th century volunteers who sacrificed themselves to the English to save their city. Better still is a “full-sized plaster model” for his extraordinary monument to Balzac, capturing the rotund novelist swathed in a vast dressing gown. “Intellectually confused” as it is, this show is undeniably “beautiful”.

Tate Modern, London SE1 (www.tate.org). Until 21 November

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Nnela Kalu’s historic Turner Prize win

Nnela Kalu’s historic Turner Prize winTalking Point Glasgow-born artist is first person with a learning disability to win Britain’s biggest art prize

-

Nigerian Modernism: an ‘entrancing, enlightening exhibition’

Nigerian Modernism: an ‘entrancing, enlightening exhibition’The Week Recommends Tate Modern’s ‘revelatory’ show includes 250 works examining Nigerian art pre- and post independence

-

Denmark's 'pornographic' mermaid statue is in hot water

Denmark's 'pornographic' mermaid statue is in hot waterUnder the Radar Town will reportedly remove voluptuous Big Mermaid, despite statue being 'arguably a bit less naked' than Copenhagen monument the Little Mermaid

-

Friendship: 'bromance' comedy starring Paul Rudd and Tim Robinson

Friendship: 'bromance' comedy starring Paul Rudd and Tim RobinsonThe Week Recommends 'Lampooning and embracing' middle-aged male loneliness, this film is 'enjoyable and funny'

-

Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture From the Torlonia Collection

Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture From the Torlonia CollectionFeature The private collection is being revealed to the public for the first time in decades

-

The Count of Monte Cristo review: 'indecently spectacular' adaptation

The Count of Monte Cristo review: 'indecently spectacular' adaptationThe Week Recommends Dumas's classic 19th-century novel is once again given new life in this 'fast-moving' film

-

Death of England: Closing Time review – 'bold, brash reflection on racism'

Death of England: Closing Time review – 'bold, brash reflection on racism'The Week Recommends The final part of this trilogy deftly explores rising political tensions across the country

-

Sing Sing review: prison drama bursts with 'charm, energy and optimism'

Sing Sing review: prison drama bursts with 'charm, energy and optimism'The Week Recommends Colman Domingo plays a real-life prisoner in a performance likely to be an Oscars shoo-in