Movie reviews: 60 of the best films of 2022

Must-watch new releases include Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio and The Silent Twins

- 1. Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio

- 2. The Silent Twins

- 3. Charlotte

- 4. Lady Chatterley’s Lover

- 5. Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery

- 6. Matilda The Musical

- 7. Bones and All

- 8. Aftersun

- 9. The Menu

- 10. Armageddon Time

- 11. No Bears

- 12. A Bunch of Amateurs

- 13. Living

- 14. Causeway

- 15. The Wonder

- 16. Barbarian

- 17. The Banshees of Inisherin

- 18. The Good Nurse

- 19. Emily

- 20. All Quiet on the Western Front

- 21. Nothing Compares

- 22. Catherine Called Birdy

- 23. Moonage Daydream

- 24. See How They Run

- 25. The Forgiven

- 26. Official Competition

- 27. Beast

- 28. Mr Malcolm’s List

- 29. My Old School

- 30. Fisherman’s Friends: One and All

- 31. Nope

- 32. Prey

- 33. Thirteen Lives

- 34. The Duke

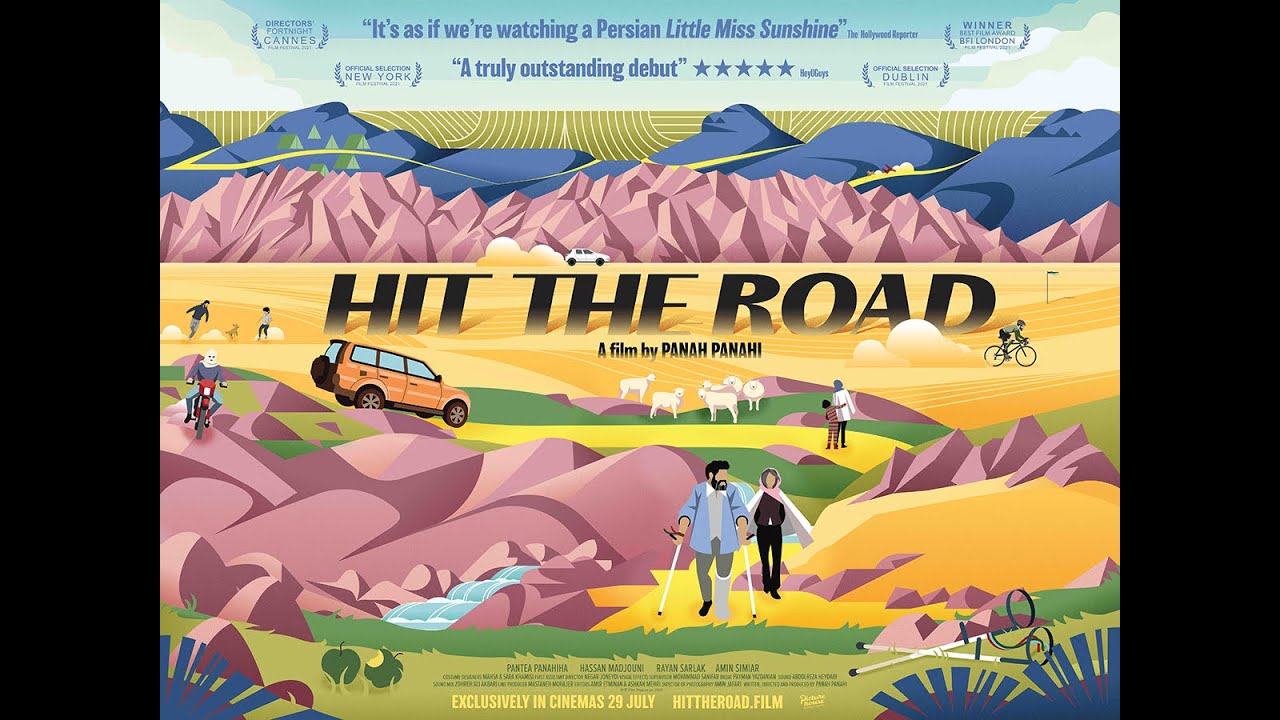

- 35. Hit The Road

- 36. Notre-Dame On Fire

- 37. She Will

- 38. McEnroe

- 39. The Railway Children Return

- 40. Thor: Love and Thunder

- 41. Turning Red

- 42. Boiling Point

- 43. Top Gun: Maverick

- 44. Licorice Pizza

- 45. Belfast

- 46. Cow

- 47. Minions: The Rise of Gru

- 48. The Batman

- 49. Elvis

- 50. Parallel Mothers

- 51. Belle

- 52. The Eyes of Tammy Faye

- 53. Operation Mincemeat

- 54. Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood

- 55. The Northman

- 56. True Things

- 57. The Outfit

- 58. Good Luck to You, Leo Grande

- 59. Playground

- 60. Men

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

1. Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio

Animation

Guillermo del Toro had apparently spent “his whole professional life” yearning to adapt Carlo Collodi’s famous tale for the screen, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail. Now he has finally produced this wonderfully dark stop-motion animation. As you might expect of the director of Pan’s Labyrinth, his Pinocchio is low on sugary sentiment. He has set it against the “glowering backdrop” of Mussolini-era Italy, and it works brilliantly. The “formidable” cast of voice actors includes Tilda Swinton as the “benign wood sprite” who awakens Pinocchio, and Ewan McGregor as the talking cricket. Pinocchio himself is voiced by the young British actor Gregory Mann, and is nothing like the “cherubic” puppet of the 1940 film. This Pinocchio is a bratty, rebellious “handful”; and it means that when he finally succumbs to “filial love”, it’s genuinely touching. The film is worth seeing, but “if I recommended it as fun for all the family, I’d expect my nose to sprout by another inch or two”. This is a Pinocchio strictly “for grown-ups”.

Actually, I’d expect children with a bit of “grit” to get a lot out of this, said Danny Leigh in the FT. Yes, it’s “sorrowful”, and it looks seriously at loss and fatherhood, but it’s never “ponderous”, and the story “zips and thrills” along, aided by some “wonderfully inventive” animation. Beautiful and unusual, the film “harkens back to the good old days of tough-love family flicks, with a lot of tears and huge emotional payoffs”, said Johnny Oleksinski in the New York Post. Pinocchio may be “100% unabashed lumber” – so woody he’d “vanish on my living room floor” – but he is still “the most endearing animated on-screen fella since Paddington”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

2. The Silent Twins

Drama

This “heartfelt, absorbing” drama tells the true story of June and Jennifer Gibbons, identical twin daughters of Barbadian immigrants who grew up in a white community in Wales, and who became known as the silent twins because they only communicated with each other, said Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian. Played as adults by Tamara Lawrance and Letitia Wright, the sisters were “effectively abandoned by the school and care systems”. They wrote reams of poems and stories, and had a novel self published, before being committed to Broadmoor in 1981 for arson and theft. Their story has been adapted before, but this version, by the Polish director Agnieszka Smoczynska, uses stop-motion puppet animation to depict “the strangeness and loneliness of their imaginings”, and also looks “subtly” at the role that race and gender may have played in the way they were “written off”. It’s a “disturbing” film, “but also tender and sad”.

The film is “overlong”, said Matthew Bond in The Mail on Sunday, but it is lovely to look at, and the twins’ “often distressing” tale is “fabulously well-told”. Some aspects work better than others, said Robbie Collin in The Daily Telegraph – Wright has a “nice line in Diana-esque sidelong glances”, and the script “wisely has the girls communicate in plain English”, rather than in the rapid-fire mix of English and Barbadian slang that they used. But the leads “chew and slurp at their consonants”, which becomes “wearing”, and the mystery at the heart of their story – why they withdrew in the first place – is never quite plumbed. This leaves the viewer “peeping confusedly” into the twins’ “sealed-off world”, without understanding why they shut themselves up inside it.

3. Charlotte

Animation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This “sombre and haunting” animation describes the life of Charlotte Salomon, the Jewish-German artist who was killed at Auschwitz in 1943 at the age of 26, said Kevin Maher in The Times. Salomon (voiced by Keira Knightley) is best known for her “semi-autobiographical masterwork”, Life? or Theatre?, a collection of 769 paintings that is sometimes described as the first graphic novel. We first meet her in 1933, when she is studying art in Berlin; she “listens dutifully” to her “stuffy professors” while nurturing her own “impressionistic” style. But “signs of dread are everywhere” – staff greet each other with “lazy Sieg Heils” – and she eventually flees to the French Riviera, where she is captured. Like other “cartoons for grown-ups”, such as Flee and Waltz with Bashir, this is a “serious meditation on politically motivated violence”, and it mostly works well.

Charlotte clearly “wants to bring Salomon’s aesthetic to life with the warm homage of its own animation”, said Tim Robey in The Daily Telegraph, but the “basic, child-friendly visuals” never do justice to her compositions, and the film feels “cocooned” in its own prettiness. And while the cast is full of “big names” – including Jim Broadbent, Sophie Okonedo and Helen McCrory (in her last screen role) – the sheer number of famous voices ends up feeling like “cameo overkill”. For an account of “an unconventional artist, the animation is disappointingly conventional”, agreed John Nugent in Empire. Even so, the film makes for “an emotional, humane viewing experience”, and should satisfy, and inform, the young audience it’s made for.

4. Lady Chatterley’s Lover

Drama

“If you’re of my generation, I expect your first encounter with D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover was the (well-thumbed) book passed around school, and then maybe Ken Russell’s full-frontal, hut-shaking, 1993 TV adaptation,” said Deborah Ross in The Spectator. Netflix’s film seems more in keeping with Lawrence’s “alternative title for the novel, Tenderness”: it is more of a “gentle, affecting, immersive love story than a sex story” – though it does fit in “plenty of sex”. Directed by Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, it stars Emma Corrin as Constance Chatterley, the young aristocrat who is ground down by the cruelty of her husband (Matthew Duckett), and who falls for Mellors (Jack O’Connell), the gruff gamekeeper. The themes of the novel – class inequities, industrialisation, “sex as natural rather than shameful” – are all addressed, “but delicately so”, and while the film “won’t set the world alight”, the story is “quietly yet rather beautifully told”.

Corrin and O’Connell are “splendid” as the lovers, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail; but it’s a pity that the novel’s jagged edges have been sanded down. “Mellors is less a piece of rough than a piece of semi-smooth”, who reads Joyce and has been “brutally cuckolded” himself. Constance, meanwhile, is depicted as such a fervent “champion of the working man”, she’s “practically Angela Rayner”, which doesn’t convince. Still, there have been worse adaptations, and it is unusually “lovely to look at”. It’s all very “tasteful and nice”, said Tomiwa Owolade in The New Statesman, with its “tender voice-overs” and a soft-lit scene in which the lovers dance naked in the rain. But it has no “erotic build-up”, and none of the book’s seductive darkness. In the end, it seems a bit “pointless”.

5. Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery

Action

A rumour has been “doing the rounds” that Glass Onion isn’t as good as Knives Out, said Charlotte O’Sullivan in the London Evening Standard. Well, that rumour is “cobblers”: Glass Onion is complex, intelligent and “outrageously funny”. Daniel Craig returns as detective Benoit Blanc, with a new crime to solve, “in a different location, among a different set of A-list faces”. Proceedings kick off when a tech billionaire (Edward Norton) invites some friends to his Greek island home to play a murder-mystery game. The story plods a bit at first, but when the twists kick in, it becomes “edge-of-the-seat stuff”.

If you ask me, Glass Onion is better than the first film, said Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian. Sure, it’s “preposterous”, but it’s properly entertaining: watching Craig parade about in a variety of “outrageous leisure-themed outfits” is a particular “joy”. The film is “crafted with guile”, said Anthony Lane in The New Yorker. But the characters are just too unlikeable; in the end, you don’t care who kills who, which leaves the movie feeling “curiously thin and cold to the touch”.

6. Matilda The Musical

Musical

When Netflix paid $500m for the rights to Roald Dahl’s works, “plenty thought it had overpaid”, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail. But on the strength of Matilda the Musical, it looks like a “shrewd” investment. Adapted from the West End hit, and featuring Tim Minchin’s music, the film could have had a “constraining theatrical feel”; but director Matthew Warchus imbues the story, about a child prodigy with telekinetic powers, with “a whole new energy”. Irish newcomer Alisha Weir is a wonderful Matilda, and it all adds up to an “exuberant joy”.

It struck me as a bit “shrill and stage-schooly”, said Matthew Bond in The Mail on Sunday; but there are plenty of compensations, not least Emma Thompson, who is “unquestionably brilliant” – and all but unrecognisable – as the vast and fearsome Miss Trunchbull. The trouble is that while it captures the darkness of Dahl, it lacks some of the author’s lightness, said Nicholas Barber on BBC Culture. I wish the film had paid attention to what Matilda tells Miss Honey in the book: “Children are not so serious as grown-ups and they love to laugh.” Viewers will laugh, but some moments are so “disturbing”, they “may scream and cry, too”.

7. Bones and All

Drama

“Anyone who travels the roads of America must sooner or later confront the question of what to eat,” said A.O. Scott in The New York Times. For the “footloose young lovers” in Luca Guadagnino’s Bones and All, it “is more a matter of ‘who’”: Maren (Taylor Russell) and Lee (Timothée Chalamet) are cannibals, who murder to sate their appetites. Yet this is “less a horror movie than an outlaw romance in the tradition of Bonnie and Clyde”, and though it is a bit ridiculous, it’s also “curiously touching”.

“Friends whose opinions I trust have gone gaga” for this film, said Danny Leigh in the FT, but it left me if not cold, then lukewarm. Russell is “excellent”, but Chalamet doesn’t really convince as a drifter capable of driving a pick-up truck, and Mark Rylance really hams it up as a veteran cannibal “huffing at the air like a macabre Oxo advert”. It may not be for everyone, but I found it “the strangest, most bewitching movie of the year”, said Tom Shone in The Sunday Times. There are “grisly sights” (lots of “bloodied snouts” and “cadavers buzzed by flies”), but this misfit love story – “by turns dreamy, sad, bloody and repulsive” – could become a new generation’s Sid and Nancy.

8. Aftersun

Drama

The Scottish director Charlotte Wells’s “astonishing feature debut” is “a portrait of paternal love, its protean nature and the lingering impact it leaves on adult life”, said Kevin Maher in The Times. Set in the late 1990s, the drama focuses on Calum (Paul Mescal), a father who has taken his 11-year-old daughter Sophie (Frankie Corio) on holiday to a low-budget Turkish resort. The film is largely made up of “sun-kissed vignettes” depicting holiday fun, but bubbling beneath the surface is “something much deeper and more difficult”: it turns out that Calum has been largely absent from his daughter’s life, and the pair are “burdened” by an urgent need to reconnect. Added to that is the hint of something darker: Calum does not explain how he broke his arm; there is bruising on his body; and though he clearly loves his daughter, there is an un-telegraphed ambiguity to his feelings. The “real kicker”, however, is that the narrative is intercut with scenes in which the adult Sophie, who now has a child of her own, constantly replays this holiday in her mind.

The film “ripples and shimmers like a swimming pool of mystery”, said Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian. Wells never forces the pace, nor labours the point. “With remarkable confidence”, she just lets the drama unspool like a “haunting and deceptively simple” short story. The result is outstanding, said Clarisse Loughrey in The Independent – a film that is gentle and contemplative, yet feels as though it is teetering on the edge of a cliff. We don’t know why this shared time has become so important to Sophie; and she doesn’t learn her father’s secrets. This is a film that “leaves behind a deep feeling of want, and it’s one of the most powerful emotions you’ll find in any cinema this year”.

9. The Menu

Drama

A darkly misanthropic fable about pompous foodie snobs, The Menu is “a wicked treat”, said Kyle Smith in The Wall Street Journal. The film is set in an ultra-exclusive restaurant on a private island, accessible only by boat and without mobile phone coverage; ruling over it with an iron spatula is a scowling martinet known simply as Chef (Ralph Fiennes). The dozen diners include a highfalutin restaurant critic (Janet McTeer), a fading movie star (John Leguizamo) and an obsessive foodie (Nicholas Hoult). His companion – played by the “superb” Anya Taylor-Joy – is the only diner who is bored by the pretentiousness of it all, which creates friction between her, her date and the supremely sinister Chef. The characterisation is a bit too broad, and the plot doesn’t entirely stand up to scrutiny – but if you like your comedy “as black as squid ink”, there’s plenty to enjoy.

With each of the diners getting their just desserts, you could describe it as a grown-up, haute cuisine take on Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, said Robbie Collin in The Daily Telegraph, with Fiennes as the Willy Wonka character who despises the kind of people who would pay absurd prices for his elaborate grub. It adds up to a comic thriller of “rare and mouthwatering fiendishness”: director Mark Mylod builds the tension masterfully, while having a good deal of fun with culinary pomposity. With targets ranging from tax havens to performance art, I found the satire rather scattershot, said Nick Hilton in The Independent. But Fiennes – who plays Chef half as a Michelin-starred maestro, half as a cult leader – is mesmerising, as is Taylor-Joy. Both have “such an otherworldly magnetism that, frankly, I’d be content to watch them read a menu”.

10. Armageddon Time

Drama

Set in a Jewish family in Queen’s, New York, as the Reagan era looms, James Gray’s new film is a “moving” autobiographical drama with a “lot to say”, said Paul Whitington in the Irish Independent. Paul Graff (Banks Repeta) is an artistic 11-year-old who befriends Johnny (Jaylin Webb), one of the few black children at his inner-city school. The pair both have ambitions, but they get into various scrapes, and eventually Paul’s parents (Anne Hathaway and Jeremy Strong) decide to move him to a local private school that has Donald Trump’s father as one of its main benefactors. Paul had already noticed that teachers treat him and Johnny differently; now the gap between them grows even wider.

The film is evocatively shot, but not everything here rings true, said Geoffrey Macnab in The i Paper. The family are portrayed as struggling: Paul’s father is a disappointed and sometimes violent man; his mother is a frazzled homemaker. Yet with the help of Paul’s wise old grandfather (Anthony Hopkins) they are able to send him to an expensive bastion of white privilege. What gives the film its resonance is Repeta’s “fierce, unsentimental” performance. This is a child who is slowly realising that “he is the beneficiary of a system that routinely gives him the benefit of the doubt”, said Ann Hornaday in The Washington Post, and this begins to “chafe against what he’s been told about his own Jewish heritage of survival against oppressive odds”. Gray’s exploration of his own “budding awareness of injustice” can slip “into self-congratulation”, but overall this is a “disarmingly honest” film about love and loyalty, and “how identity morphs from one generation to the next”.

11. No Bears

Drama

With Iranian women rising up against their country’s oppressive regime, this is a good time to watch No Bears, said Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian – starring, and directed by, the recently jailed Iranian dissident Jafar Panahi. In the film, he plays “Jafar Panahi”, a film director who has been banned from making films or from leaving Iran, who nevertheless decides to shoot a film in a Turkish town just over the border. Panahi delegates the “hands-on direction” to his assistant Reza (Reza Heydari), while watching proceedings over Skype from a rented room in a nearby Iranian village. There, he falls foul of village chiefs, who accuse him of taking an incriminating photo of a young woman who is about to undergo an arranged marriage, a photograph he insists does not exist. The “meta-fiction” at the heart of No Bears can feel a bit “emotionally obtuse”, but don’t be put off: this is a film of real intelligence and “moral seriousness”.

No Bears is shot through with “wider political resonances”, said Mark Kermode in The Observer, but it’s also “a piercingly self-aware portrait of an artist”. It is remarkable that “despite all that he has faced”, Panahi has “the wit and humility” to question his art with such “candour and self-deprecation”. That Panahi was able to make a film at all is astonishing, said Deborah Ross in The Spectator, let alone a film that is as funny, engrossing and thought-provoking as No Bears. The more you think about it, the more it reveals about “lives made small by restrictions that can and do result in tragedy”. Daring and brave, it is partly about the power of film; it is also “great cinema”.

12. A Bunch of Amateurs

Documentary

The members of the Bradford Movie Makers club have been making “virtually zero-budget films with rickety production values” since 1932, said Cath Clarke in The Guardian. Kim Hopkins’s “warm and rather wonderful” documentary about them “finds comedy in their idiosyncratic passion, without ever being mean or mocking”. In the club’s heyday, it had a waiting list of several years; today, it is on its uppers. Its numbers are dwindling, and it is five years behind on the rent for its crumbling clubhouse. Still, “some big personalities” remain, including Colin, a retired carpenter in his 80s whose wife lives in a dementia care home; and Phil, the club’s “enfant terrible”, a “sweary” fortysomething “lad” who makes short films with titles such as The Haunted Turnip. There are funny moments, but this is a thoughtful film that has “unexpectedly deep things” to say about “camaraderie, community and male friendship”.

A Bunch of Amateurs celebrates a “certain kind of Englishness” – eccentric, passionate and “engagingly daft”, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail. As the documentary unfolds, it becomes clear that there is no mushy ending in store: the films produced by the club’s members will not get much of an audience, and “in truth don’t deserve one”. But that’s not the point: its members are “amateurs in the original sense of the word, making films for the love of the process”. The club is a lifeline for them, said Alistair Harkness in The Scotsman. The “very act of making and screening films” offers them “much-needed respite from their everyday troubles”. Still, Hopkins’s attempts to turn the club’s precarious future into a comment on the state of the film industry feels “a little strained”.

13. Living

Drama

“Not much happens” in Living, Kazuo Ishiguro’s “impeccably written” new film, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail; but what doesn’t happen “doesn’t happen exquisitely”. Set in 1950s London and directed by Oliver Hermanus, it stars Bill Nighy as Mr Williams, a “stiffly venerable” bureaucrat who spends his days processing planning applications for London’s County Council. A widower, he is a “benignly authoritative presence” in the office and “a politely tolerated one” at the home he shares in Esher with his stolid son and daughter-in-law. When he learns that he has terminal cancer, however, he resolves to add “colour to his monochrome existence”: he skips work, forms a platonic but “faintly scandalous friendship” with an ex-employee (played “delightfully” by Aimee Lou Wood), and champions the efforts of a group of East End mums to build a children’s playground on a bomb site. Living is not exhilarating, but it’s beautiful in its melancholy way, “and Nighy is simply superb”.

This is one of those rare films that “may actually inspire you to live differently and, perhaps, do something of value before it’s too late”, said Deborah Ross in The Spectator. A remake of the great Japanese film Ikiru (1952), it is as “heartbreakingly tender” as the original, and “asks the same question – what makes a life meaningful? – but this time with Englishness, bowler hats, the sweet trolley at Fortnum’s and Bill Nighy”. Really, “what more could you want?” Everything “comes together” in Living, said Tom Shone in The Sunday Times: “the delicious ache” of Ishiguro’s script; Jamie Ramsay’s lovely, “desaturated cinematography”; and, above all, Nighy. As an actor, he is as reliable “as an old umbrella”. Here, he has “a chance to unfurl fully” in a role worthy of his talents.

14. Causeway

Drama

“Causeway is an excellent, moving, determinedly low-key slice of US indie cinema” that could easily have slipped under the radar were it not for the presence of Jennifer Lawrence, said Tim Robey in The Daily Telegraph. She stars as Lynsey, an engineer for the US military who moves back in with her mother in New Orleans, having narrowly missed being blown up in Afghanistan by a bomb that claimed the life of one of her comrades. Dosed up on medication and struggling with a “drastic case” of PTSD, Lynsey drifts through her hometown “with a sense of futility and woozy disconnectedness”. When she meets James (Brian Tyree Henry), a mechanic who lost a leg in an accident a few years earlier, these two “broken people” bond, and the film “gently ignites”. This is a “spare, sensitive and unadorned” film, and it’s well worth seeing.

Lawrence has wasted almost a decade on “soulless blockbusters” and “arthouse misfires”, said Kevin Maher in The Times; so it’s a joy to see her finally produce “the kind of restrained, internalised performance” that made her name in the 2010 indie film, Winter’s Bone. But she is nearly outshone by her co-star, who imbues his character with “humour, compassion and hangdog dignity”, and grounds the film in gravitas. Causeway is superbly acted, agreed A.O. Scott in The New York Times, but once James and Lynsey are brought together, the film seems unsure “what to do with them”. The “symmetry of their physical and psychological wounds” feels far too “neatly arranged” to be credible, and while Henry and Lawrence do what they can, they can’t quite “bring the script’s static and fuzzy ideas about pain, alienation and the need for connection” to life.

15. The Wonder

Drama

Florence Pugh is “terrific” in this period drama set in Ireland in 1862, just a few years after the Great Famine, said Matthew Bond in The Mail on Sunday. She plays Lib, an English nurse sent to a remote village to observe an 11-year-old girl (an “impressive” Kíla Lord Cassidy), who is reported to have lived for four months without eating. Lib suspects this “miracle” is a con, perpetrated by the child’s family, and resolves to uncover the truth, aided by a sharp-witted journalist played by Tom Burke. The story is unappealingly framed: it starts and ends in a modern-day film studio. But the rest is well done and there are some fine performances. A word of warning, though: The Wonder is so darkly shot that “anyone watching on Netflix will need the living room lights off and the curtains drawn” to have a clue what’s going on.

Adapted from Emma Donoghue’s 2016 novel, it is an “arrestingly strange” and “distinctively literary tale of innocence, horror and imperial guilt”, said Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian. Without Pugh’s “sensuality, passion and human sympathy”, the film could have teetered “under the weight of its contrivances”; but thanks to the “pure force” of her performance, it works. The cast is “stellar” and the cinematography “striking”, but I found it frustratingly lacking in nuance, said Tara Brady in The Irish Times. “Every plot progression and twist” – from the big reveal to the ludicrous denouement – is so heightened, it makes “the average telenovela look like Bicycle Thieves”. Unless “you are absolutely fine with weapons-grade melodrama”, I’d steer clear.

16. Barbarian

Horror

Barbarian is a “playful” horror film that uses “one of the minor pitfalls of modern life” as a “satisfying plot hook”, said Ed Potton in The Times. Georgina Campbell plays Tess, a documentary researcher who arrives in a “down-at-heel” neighbourhood of Detroit one night for a job interview, only to find that the Airbnb she’d booked has been rented to someone else on a different app. That person is Keith (Bill Skarsgård), who comes across as a “nice guy” equally puzzled by the situation. Tess is wary even so, but she lets her guard down when they share a bottle of wine and bond over their passion for music. Soon, however, she discovers that the house is harbouring a horrifying secret. Often “gleefully scary”, this is an “inventive tale that’s full of disarming twists and #MeToo undertones”, and it makes evocative use of Detroit’s “abandoned buildings and sense of decay”.

This low-budget production has done “excellent business at the US box office – and deservedly so”, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail: it’s smart, scary and at some points “very funny”. It’s just a pity that the plot gets less credible as the film goes on. Still, it’s “done with tremendous swagger”, and “those few good laughs make the chills even chillier”. I’d say that it is only “competently made”, said Benjamin Lee in The Guardian: it feels “curiously flat”, and its echoes of horrors such as Don’t Breathe and The People Under the Stairs are not flattering. It’s also frustrating to watch Campbell, “an actor of clear intelligence”, glumly navigate “a character of deep stupidity”: she starts the film as a “smart and careful woman”, and ends it as a “maddeningly dim-witted” one.

17. The Banshees of Inisherin

Comedy-drama

Tragedy and comedy are “perfectly paired” in this “deliciously melancholy” new film from Martin McDonagh, said Mark Kermode in The Observer. The Banshees of Inisherin reunites the director with the stars of his 2008 debut, In Bruges: Colin Farrell plays Pádraic, a dairy farmer on the fictional island of Inisherin, who pops into his best friend’s house one afternoon in 1923, as the Irish Civil War is raging distantly on the mainland, to find that Colm (Brendan Gleeson) has no interest in coming to the pub. In fact, Colm has no interest in being friends anymore. “Depressed by a sense of time slipping away”, and determined to spend his remaining years composing fiddle music of lasting value, he has decided to rid himself of Pádraic’s “aimless” chatter. And silly though his resolution seems to other islanders, Colm is taking it deadly seriously: when Pádraic tries to persuade him to rethink, Colm threatens to cut off one of his own fingers whenever Pádraic speaks to him. The film swings “between the hilarious, the horrifying and the heartbreaking”; and the cast is “note-perfect”.

This sad and startling film is my favourite of the year so far, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail. The characters have real depth; the dialogue is “exquisitely crafted”; the score is “glorious”. And while McDonagh has come under fire for peddling Irish stereotypes, the only flaw I can detect is “in the dentistry department”: I suspect “the smiles of the rural Irish 100 years ago were rather more peat-brown than pearly-white”. The Banshees of Inisherin is, by my reckoning, “a perfectly formed piece”, said Kevin Maher in The Times. Consistently witty and visually ravishing, it is “unafraid to ask serious questions about life as it is, and should be, lived”. It is, in short, a work of “proper art”.

18. The Good Nurse

Thriller

This Netflix thriller is based on the real-life case of Charles Cullen, a New Jersey nurse who was arrested in 2003 having apparently killed hundreds of patients, said Edward Porter in The Sunday Times. He is played by Eddie Redmayne, who proves he is “more than able to conjure up a desiccated, quietly creepy” murderer; while Jessica Chastain “adds humanity” as Amy Loughren, a struggling nurse and single mother who bonds with Cullen when he starts working at her hospital, but eventually plays a key role in bringing him down, as it becomes clear that he has been covertly administering lethal overdoses. The film is essentially a report on the administrative flaws that allowed Cullen to work in a series of hospitals without detection for so long: and while it’s a little “grey and plodding in its style”, the two lead performances make it well worth watching.

Directed by the Danish film-maker Tobias Lindholm, this is one of those films that “operates at a low temperature, simmering its ingredients until the final reel”, said James Mottram in the Radio Times. There are some “terrifying moments”, but anyone “looking for a scary serial killer movie, in true Silence of the Lambs style”, would do better to sit it out. Still, “as a character study of a disturbed mind”, the film “pushes all the right buttons”. The Good Nurse is entertaining enough, said Michael O’Sullivan in The Washington Post. But ultimately, it’s “the kind of dime-a-dozen true-crime tale that typically goes straight to streaming”. I was left wondering why two such talented actors “thought something this slight, this weightless, this forgettable was ever worth their time”.

19. Emily

Drama

Emily Brontë died in 1848 at the age of 30 with just one novel to her name, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail. “But that novel was Wuthering Heights.” And this “beguiling film” imagines what might have inspired her to write it. Written and directed by Frances O’Connor, it offers a speculative, even mischievous, take on the author’s life, about which precious little is known. We begin at the end, with Emily (Emma Mackey) on her death bed and her sister Charlotte (Alexandra Dowling) aghast at the contents of her novel, but astounded by its merit. “How did you write it?” she demands – and we are whisked back in time to find out. Emily, we learn, is considered the “weird one” of the Brontë girls; a loner who pours her thoughts into her stories. When her clergyman father (Adrian Dunbar) takes on an attractive new curate (Oliver Jackson-Cohen), she isn’t impressed, but her cynicism slowly turns to love. The film is “handsome-looking”, beautifully acted, and the script is “superb”.

What a “daring and ravishing” film this is, agreed Deborah Ross in The Spectator. It’s a period drama that takes liberties, but “there’s no Billie Eilish on the soundtrack or breaking of the fourth wall or jokey intertitles, which is a mighty relief”. Aspects of the plot may sound “insane” – at one point, Emily tries opium; at another she is sent to retrieve her brother from a pub, and returns drunk herself. (What? “Emily Brontë, drunk! And high!”) But within the film’s “internal logic”, it all makes sense. Mackey is on splendid form here, said Charlotte O’Sullivan in the London Evening Standard. But the film is based on the simple premise that “being on Team Emily means sticking the boot into her sisters”. Yet the Brontës were team players. “Why is that not a story worth telling?”

20. All Quiet on the Western Front

Drama

Erich Maria Remarque’s classic 1929 anti-war novel has been adapted for the big screen twice before, said Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian; but this is the first German-language version – and the result is a “powerful, eloquent” and “conscientiously impassioned” film, well worth seeing. Felix Kammerer plays Paul, a German teenager who enlists with his schoolfriends in a burst of patriotic fervour towards the end of the First World War. He is anticipating “an easy, swaggering march into Paris”; instead, he finds himself mired “in a nightmare of bloodshed and chaos”. Meanwhile, in a parallel plot (not in the book) a real-life German politician, Matthias Erzberger (Daniel Brühl), is trying to negotiate an armistice. The film is “a substantial, serious work, acted with urgency and focus”, with battle scenes that seamlessly combine CGI with live action.

All Quiet on the Western Front is “reminiscent of a darker, much tougher 1917”, said Kevin Maher in The Times. The set pieces are spectacular, but they are humanised by “incidental details” – the soldiers learn, for instance, that “shoving their hands down their trousers keeps their trigger fingers warm”. Some images linger long after the film is over: “a mutilated body hanging in the woods like something from Goya’s Disasters of War”, a battlefield of charging soldiers so suddenly perforated by Allied machine guns “that a faint pink mist, made of tiny droplets of blood, fills the air”. “See it on the biggest screen possible. Then watch it again on Netflix.” There are moments when the film resembles a preposterously beautiful PlayStation game, said Ed Power in The Daily Telegraph. But its evocation of war ends up connecting “where it truly matters: in the gut”.

21. Nothing Compares

Documentary

“It’s been 263,000 hours and 10,960 days – give or take – since Sinéad O’Connor tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live,” said Leslie Felperin in the FT. The Irish singer’s 1992 protest against clerical abuse in the Catholic Church nearly wrecked her career – not that she “gave much of a toss”, as becomes clear in this “rousing” documentary.

Director Kathryn Ferguson pieces together the pop star’s life through archive footage and interviews, including with O’Connor herself; the picture that gradually emerges is of an inveterate rebel whose refusal to be bossed around began when she shaved her head early in her career, in defiance of her record company.

The film works as a study of O’Connor’s “complex character”; but what a pity that Prince’s estate refused to give the film-makers permission to use her unforgettable 1990 cover of his song Nothing Compares 2 U.

22. Catherine Called Birdy

Comedy

Lena Dunham, creator of the cult HBO comedy-drama Girls, is “perhaps not the first name you would think of to adapt and direct a period film set in medieval England”, said Wendy Ide in The Observer. But this teen comedy, based on the 1994 novel by Karen Cushman, is a “peppy, irreverent” triumph.

Bella Ramsey plays Lady Catherine, a bird-loving 14-year-old (hence her nickname, Birdy), who finds herself in a sticky situation when her “charming but feckless” father (Andrew Scott) fritters away the family fortune. His solution is to marry Catherine off to a “title-hungry gentleman of means”; the trouble is, Catherine likes her life as it is – so she sets about scaring off her suitors with “every unsavoury trick” she can conjure.

Ramsey excelled as a “poised” child-queen in Game of Thrones, but here she brings welcome mischief to her role; and Dunham directs with “liberal use of goats, geese and chaotic energy”. The film has a “refreshingly forthright approach to everything from puberty to the status of 13th century women”, and it’s a “delight”.

23. Moonage Daydream

Documentary

“David Bowie was a rock star like no other,” said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail, so it’s fitting that Moonage Daydream is a truly “singular documentary”, ostensibly about his life, but more a journey through his “relentlessly mercurial mind”.

Writer and director Brett Morgen was granted rare access to “every nook and cranny” of Bowie’s archive, and has made excellent use of all that material: one of the “primary joys” of this film is “how little [of it] we’ve seen before”.

This “immersive, trippy, hurtling, throbbing” film takes us as close to knowing Bowie “as an actual person as we are ever going to get”, said Deborah Ross in The Spectator. Morgen covers his life from “cradle to grave”, but not in the usual way: there are no talking heads or clichéd graphics, for instance. Instead, excerpts from interviews allow Bowie essentially to narrate the film himself, while his music – remixed by his long-time producer Tony Visconti – provides the lushest of soundtracks.

24. See How They Run

Comedy

No one has ever managed to make a film of The Mousetrap, said Tim Robey in The Daily Telegraph, and for one very simple reason: Agatha Christie insisted there should be no film adaptation until six months after the play closed – which, of course, it never has. Using that very stipulation as a motive for murder, a crafty team have come up with the next best thing: a “delightfully absurd” whodunnit about the play itself. It’s set in 1953: the cast is celebrating the play’s 100th performance when a telegram arrives from Christie saying she cannot join the party, but has sent a big cake instead. Sure enough, within ten minutes someone is dead. The film bounces with a sense of fun worthy of Tom Stoppard – whose name, in a running joke, is given to the detective (Sam Rockwell). The suspects include a glamorous impresario (Ruth Wilson), a dandyish playwright (David Oyelowo) and a furtive producer (Reece Shearsmith). With a seam of pure English silliness, this is a “whizzy fairground ride in theatreland, powered entirely by the thought of a literary icon spinning in her grave”.

See How They Run is “as sweet and light as a fondant fancy”, said Clarisse Loughrey on The Independent. It’s the kind of ensemble film that plays like a tennis match, with the cast skilfully lobbing one-liners at each other and giving knowing winks to the camera. But the real joy is the rapport between the investigating plods, said Ian Freer in Empire. Rockwell brings “grizzled, Walter Matthau-type charm” to the cynical inspector; Saoirse Ronan is even better as an over-eager WPC star-struck by the suspects. Combining farce, backstage drama, crime potboiler and police procedural, this is a “fast, funny and frequently stylish” movie steeped in the atmosphere of 1950s London.

25. The Forgiven

Drama

If you “like your humour wickedly dark, bordering on the unpleasant”, then “The Forgiven could be the film for you”, said Kate Muir in the Daily Mail.

Ralph Fiennes plays David, a high-functioning English alcoholic driving his American wife Jo (Jessica Chastain) to a swanky party at a castle in Morocco. The couple are arguing as usual when a teenage boy “suddenly appears in their headlights and is killed on impact”. They’re on a dark rural road, so they stash the boy’s body in the back of the car, and press on to the castle, which is owned by an “outrageous” couple (Matt Smith and Caleb Landry Jones).

Adapted from a novel by Lawrence Osborne, this is a watchable film that makes good use of its attractive Moroccan settings, said Matthew Bond in The Mail on Sunday. The story, though, is “lacking in tension”, and director John Michael McDonagh, who made The Guard (2001) and the “brilliant” Calvary (2014), can’t decide whether his “first priority is to amuse or serve up something meaty and moralistic”. By the time he’s made up his mind, “it’s almost too late”.

You do “have to do your own moralising” with this film, which is “always a drag”, agreed Deborah Ross in The Spectator. But there are reasons to see The Forgiven: Fiennes and Chastain are both “terrific”, and it’s a “compelling” tale, even if human nature doesn’t come out of it at all well.

26. Official Competition

Comedy

Films that satirise the film industry itself are, in my experience, “seldom funny – or even fun”, said Leslie Felperin in the FT. Yet this “irresistibly silly” Spanish comedy manages to be both, thanks in part to Penélope Cruz, who brings both comic and dramatic flair to the role of Lola, a maverick film director hired by a “dilettante squillionaire” to make an art film that will be his legacy. This film is to be about two estranged brothers and, in order to pit two real-life opposites against one another, Lola casts a “high-minded, classically trained Argentine import” (Oscar Martínez) as one of the brothers, and a “swaggering Spaniard” (Antonio Banderas) as the other. During rehearsals, the film’s two leading men “grow to loathe one another” as Cruz puts them through their paces. Directors Mariano Cohn and Gastón Duprat “keep the comedy deadpan” to create a film that has the pleasing feel of “an old-school screwball comedy, albeit one with very dark edges”.

Official Competition certainly has a “top-notch” cast, said Matthew Bond in The Mail on Sunday. But despite their “best endeavours”, I can’t see this film having mass appeal. It seems to have been “made for the slightly smug, aren’t-we-cool film-festival crowd”. Well then, I guess I must be among them, because I loved this “Spanish-language gem”, said Tim Robey in The Daily Telegraph. Martínez and Banderas are “splendid”as the warring leads, while Cruz, “who’s never looked more divine”, really “nails” it as the “visionary nutcase” director. The film’s set pieces will make you roar with laughter, and the whole thing is brilliantly finessed. “Smart comedy is already a rarity; smart comedy that looks this good is a once-in-a-blue-moon event.”

27. Beast

Action

For years, blockbuster films have been posing questions such as “How would Spider-Man cope with PTSD?” and “How would Buzz Lightyear process personal and professional failure?”, said Robbie Collin in The Daily Telegraph. So there’s a “Zen-like release” in watching one that “ponders nothing more onerous than ‘who would win in a fight between Idris Elba and a marauding big cat?’”

In Beast, Elba plays a widowed doctor seeking to reconnect with his teenage daughters (Iyana Halley and Leah Jeffries) by taking them to their late mother’s birthplace in South Africa. He has amends to make – and “his own conscience to salve” – as their marriage fell apart just as she was becoming ill with cancer. Then a “huge, drooling” lion attacks, and keeps attacking, and Elba’s “appealingly fallible hero” finds himself fighting for his family’s survival,“not just figuratively, but also in a more pressing, oh-dear-we’re-about-to-be-eaten sense”. The resulting “man-versus-animal death-match” provides a “grippingly efficient thrill-ride”, whose “93 minutes seem to pass in around 15”.

I am not sure “whether this was ever intended to be a serious film”, said Deborah Ross in The Spectator. Perhaps it doesn’t matter. It is fun, in a “shlocky, gory, silly way”; it has perfectly decent CGI, it zips along, and it will delight anyone who’s yearned to see Elba “wrestle a lion and then punch it full in the face” – “not my dream especially, but each to their own”. Beast doesn’t go “anywhere you can’t predict from the trailer”, said Benjamin Lee in The Guardian, but the pace rarely slackens, and it’s “directed – by Baltasar Kormákur – with more flair than one often gets from such material”. It’s a “B-movie”, to be sure, but one that’s “bringing its A-game”.

28. Mr Malcolm’s List

Drama

Adapted by Suzanne Allain from her own novel, this “engagingly silly and self-aware comedy” is a “romantic Regency romp in the diverse, postcolonial ‘alt-history’ universe popularised by Bridgerton”, said Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian. Our heroine is Julia Thistlewaite (Zawe Ashton), “a highly strung young woman” hunting for a husband in fashionable London society, who learns that the city’s most eligible bachelor, the Hon. Jeremy Malcolm (Sope Dirisu), has a “secret list” of attributes that he is looking for in a bride.

When Julia fails to meet these requirements, she decides to seek retribution, by asking her best friend, a penniless clergyman’s daughter (Freida Pinto), to ensnare Malcolm “by faking the ten comely attributes from his list”. Malcolm falls for the conspiracy and is soon entranced – as is an ex-cavalry officer (Theo James), a man “so tight-trousered his fly button will surely have someone’s eye out”. This is “good-natured entertainment” that clearly has no ambitions other than to amuse, and in that, it succeeds quite nicely.

It didn’t amuse me much, said Kevin Maher in The Times. So lightweight as to be “almost meaningless”, the film has just one redeeming feature: Ashton, whose “stellar” performance just about keeps the show on the road. Pinto and Dirisu, by contrast, seem to have set their “charisma phasers” to “power-save mode”. The film does feel slightly “paint-by-numbers”, said Dulcie Pearce in The Sun. The set-up scenes are “painfully long and unfunny”; the script is “plodding”; and though the “costumes and finery” are nice to look at, you will soon find yourself yearning for Mr Darcy.

29. My Old School

Documentary

This “impish and riveting” documentary recounts the stranger-than-fiction case of the man who called himself Brandon Lee, said Robbie Collin in The Daily Telegraph. In 1993, a curly-haired “teen” enrolled at a Glasgow school under audaciously false pretences: he was, in fact, a 30-year-old man who had decided to pretend to be 16 so that he could resit his exams and get into medical school. When the scheme came to light in 1995, Lee became a “minor media sensation”, but he has become publicity-shy in recent years, so director Jono McLeod – who was one of his schoolmates – devises a “cunning compromise” here: an audio confession from Lee that is lip-synched by the actor Alan Cumming, and interspersed with interviews and re-enactments of key moments. The film initially “bubbles along entertainingly”. Later, though, it becomes genuinely “unnerving” as it deals with the most “awkward” part of the story: Lee’s on-stage kiss with a teenage girl in a school play.

Even if you’re familiar with Lee’s story, as I was, said Deborah Ross in The Spectator, you’ll wonder as you watch this documentary: “How could they not know? He could drive a car! He liked Chardonnay! He introduced his classmates to retro music!” The film doesn’t have all the answers – there’s clearly something “disturbed” going on here that is never fully plumbed – but you’ll “enjoy the ride” anyway.

Considering how “deeply weird” Lee’s behaviour was, I found My Old School “oddly heart-warming”, said Alistair Harkness in The Scotsman. McLeod adopts an appealingly “bemused” tone throughout; and while Lee is shown to be a “slippery character”, the film is no hit job. Rather, “it’s an expertly crafted tale of deception”, told “with a playfulness that is eminently watchable”.

30. Fisherman’s Friends: One and All

Drama

“Break out the pea coats, chunky sweaters and bushy beards, for Fisherman’s Friends is back,” said Matthew Bond in The Mail on Sunday. “Yes, three years after the unexpectedly successful film put the Cornish village of Port Isaac on the cinematic map, and reminded us all that sea shanties are rather wonderful as long as there aren’t too many of them”, the team has returned with a sequel that picks up about a year after the 2019 movie left off. The shanty-singing band have now stormed the UK charts, and are learning that “fame, modest fortune and life on the road” can take a toll. Singer Jim (James Purefoy) is having an especially rough time of it, hitting the bottle as he grapples with the death of his father. This is “lightweight, late-summer fun”, packed with “broad comedy” and “high drama”, but it’s also “surprisingly emotional”, and it’s buoyed by Purefoy’s “nomination-grabbingly good” performance (“yes, seriously”). “As sequels go, me ol’ hearties, it’s terrific.”

It didn’t do it for me, said Wendy Ide in The Observer. Rather than tell one story well, it “weaves drunkenly between themes”: bereavement, substance abuse and male mental health all crop up, and the film even saunters into “the murky waters of the woke debate”. Subplots are used as mere glue to “tack together the Cornish tourist board-approved shots of cornflower-blue waters and cloudless skies”. There is also “far more rousing close-harmony singing than anybody really needs to hear in their lifetime”.

This is a nice-looking, “well-made film” held together by a “very likeable cast”, said Cath Clarke in The Guardian. But it’s wearyingly predictable, and has a rather “factory-made” flavour. I’m afraid this franchise feels to me “like it’s hit the rocks”.

31. Nope

Thriller

Nope is “a film that does for open skies what Jaws did for the beach, and The Wicker Man for Hebridean getaways”, said Robbie Collin in The Daily Telegraph. It’s the third feature from Jordan Peele, director of the psychological horror smash hit Get Out; and like that movie, it’s an entertaining thriller with a “rich and troubling substance bubbling underneath”.

Daniel Kaluuya stars as the taciturn OJ, who, along with his more gregarious sister (Keke Palmer), trains horses on a ranch in southern California for use in films and TV. When we meet them, they’re dealing with the mysterious death of their father, killed by a small object that has dropped from the sky. Nope “treats us to all the tricks from the flying saucer canon” – false alarms, “teasing peeks” – while remaining “excitingly fresh”.

It’s one of the movie events of the year, “if not the decade”, said Charlotte O’Sullivan in the London Evening Standard. A “playful riff on our obsession with UFOs, Nope blurs sci-fi, horror and cowboy movie tropes, while finding the time to explore racism, climate change and 1990s sitcoms”. It’s also a deeply weird film that is “likely to invade your dreams”.

The special effects aren’t bad, said Matthew Bond in The Mail on Sunday, but as a whole the film is “painfully slow, overburdened with plot and not exactly awash with the sort of performances to make you pleased you bought a ticket”. I’m afraid “it’s a big ‘nope’ from me”.

32. Prey

Action

Prequels make “my heart sink”, said Wendy Ide in The Observer: all too often they’re used just to “squeeze a little more juice out of an already dead and desiccated franchise”. Prey, however, which revives the Predator series for a seventh outing, “is different”. For one thing, it’s set 300 years before the earlier films, on the Great Plains of North America, where Comanche life is presented in rich, authentic detail. Our heroine is Naru (Amber Midthunder), a warrior whose prodigious survival skills are put to the test when an alien creature starts killing everything in its path. To director Dan Trachtenberg’s credit, the film “stays true to the essence” of the 1987 original – it’s “stylishly violent, stickily graphic” and “impossibly tense” – while also succeeding “as a self-contained entity”.

I was impressed by this addition to the franchise, said Benjamin Lee in The Guardian. “It feels genuinely new to see a genre film of this scale” anchored by an Indigenous American cast. This is not just a victory of representation; it also ensures that a story “we’ve seen a few too many times before” is told in an interestingly fresh way. It’s just a shame that the film, which is beautifully shot, and has some “intricate, well choreographed” action sequences, is going straight to Disney+.

What I liked about this “audacious action flick” is that it reinforces the forgotten value of “dramatic jeopardy”, said Kevin Maher in The Times. Its characters are seen “in actual danger of harm, injury or even death, rather than just punching stuff repeatedly for two hours while wearing a superhero costume”. Of course Midthunder’s stellar performance helps too; in a few short scenes, she conveys so much about Naru that when the “great big bloody predator” swoops to get her, we “really care”.

33. Thirteen Lives

Drama

We all remember the events of 2018, when 12 boys and their football coach were trapped in a flooded cave network in Thailand, and were rescued – after 18 days – by an international team of cave divers led by two “plucky Brits”, said Matthew Bond in The Mail on Sunday. What we may not know is the detail; what it felt like to be trapped underground, or to dive underwater into darkness.

Now, thanks to Ron Howard’s new film, we do. This is a dramatisation “that works on just about every level”: it’s thrillingly paced, “culturally sensitive” and beautifully acted. Viggo Mortensen and Colin Farrell play the two British divers, and though neither are British, they pull it off brilliantly: Mortensen captures the “British blokey bolshiness” of ex-firefighter Richard Stanton, while Farrell is “quietly perfect” as IT consultant Jonathan Volanthen. The film is coming to Amazon Prime, but its “exceptional” underwater photography makes it well worth seeing on a big screen.

When he’s on form, Howard makes “warm-hearted, decent and diligent” films characterised by a kind of “Centrist Dad” level-headedness, said Robbie Collin in The Daily Telegraph. And this “compulsively watchable” dramatisation is him at his best. The diving sequences are so tense you’ll be “sympathetically shrinking in your seat”; and wisely, Stanton and Volanthen are not depicted as “saviours swooping in from lands afar”, but as gruff hobbyists who clash with each other as well as with the Thai rescue team.

The film is certainly compelling, said Edward Porter in The Sunday Times, but to me it lacks the “dramatic flair” of Howard’s previous true-life disaster movie Apollo 13. Viewers might do better to seek out The Rescue, a riveting 2021 documentary about the same events.

34. The Duke

Comedy

I could probably watch this old-fashioned comedy caper “all day every day for the rest of my life,”, said Deborah Ross in The Spectator. Directed by the late Roger Michell (of Notting Hill fame), it recounts the notorious theft of Goya’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery in 1961, and stars Jim Broadbent as Kempton Bunton, the idealistic taxi driver from Newcastle who claimed to have committed this audacious crime.

The film is “wonderfully funny”, but “thoughtful and tender” too; if you don’t find Bunton – the “ordinary fella prompted to do an extraordinary thing” – wholly “loveable” from the off, I’ll “refund your ticket”.

This warm and witty film has the “zing of a classic Ealing caper”, said Robbie Collin in The Daily Telegraph. Broadbent and Helen Mirren, who plays Bunton’s wife, have rarely been better. And while the film is unafraid to “go broad – one stirring sequence is scored to the hymn Jerusalem, for goodness’ sake” – it touches on serious themes (about how, for instance, institutions should serve the people who fund them); and its subtlety “often catches you off guard”.

There are moments when it ladles on the “working-class nobility” a bit thick, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail: we see Bunton standing up against racism, and being sacked as a taxi driver for waiving a war veteran’s fare; but Broadbent “keeps it real at every turn, and manages a passable Geordie accent to boot”, while Mirren, who does frumpy and downtrodden as well as she does elegant hauteur, is a “superb foil”.

Although she is often exasperated by her “placard-waving husband”, we never doubt the depth of their love. For what proved to be his swansong, Michell has given us a truly “lovely film”.

35. Hit The Road

Drama

For my money, “the best release of the week by far” is this Iranian film by debut director Panah Panahi – the son of the recently jailed filmmaker Jafar Panahi, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail. It follows a family of four who are driving to the Turkish border, because the elder son (Amin Simiar) needs to flee the country. We presume that it is for political reasons, but “really, those reasons don’t matter”. This is a film about families; the profound love that holds them together, and the ways they can fall apart. The film has a “strong undercurrent of sadness”, but it is a “charmer. I was hooked from the opening scene, in which the irresistibly cute but unstoppably naughty” younger son (Rayan Sarlak) “mischievously hides his father’s mobile phone down his pants”.

Sarlak is one of the most “believably annoying” kids you’ll ever meet on screen, said Tim Robey in The Daily Telegraph, but Pantea Panahiha is “wonderful” too as his mother, “forever silently asking herself whether they’ve reached the point of no return”. The film could “have had the gloom of a Stygian ferry ride”; instead it “pulsates with vivacity”. Hit the Road is a “miraculously accessible piece of entertainment” about people who “stay brave” even as they are “drowning”.

Most of the action takes place within the confines of the car, a private space that can be an “island of freedom” in the director’s home country, said Christina Newland in The i Paper; but Panahi punctures “his closer camera work with some stunning wide shots of the landscape nearby”. It’s a wonderful, life-affirming film; what a crying shame, then, that it has not yet been shown in Iran.

36. Notre-Dame On Fire

Drama

The words “dramatic reconstruction” can be a bit of a dampener, said Larushka Ivan-Zadeh in The Times, but “I’d defy anyone” not to be gripped by “this spectacular minute-by-minute reconstruction of the blaze that engulfed Paris’s iconic cathedral” on 15 April 2019. Directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud (The Name of the Rose), it captures the efforts of French firefighters to contain the inferno that nearly razed Notre Dame to the ground, combining dramatic recreation with archive footage, digital effects and amateur video. The result is a “documentary/thriller/disaster movie” mashup that doesn’t entirely pull it off; but if you do get the chance to see it on an Imax screen, take it.

It’s still unclear how the fire broke out at Notre Dame, said Phil de Semlyen on Time Out; and Annaud wisely “hedges his bets” on this mystery “by showing us both a workman’s rogue ciggie and an electrical short”. The film comes into its own when the “almost demonic” inferno, raging at up to 1,300°C, starts “melting scaffolding and pouring molten lead” through the mouths of the cathedral’s gargoyles. And yet alongside this drama, there are some “surprisingly funny” moments. “The church is 800 years old,” notes a bystander at one point. “We should call your mother,” replies his wife.

The film rather revels in the disaster, said Wendy Ide in The Observer, but it does capture the fire’s “daunting rage”, to often “eyebrow-scorching effect”. What we don’t really get is a “sense of emotional engagement with key characters”, partly because so many of them are “concealed behind breathing apparatus”. In its place, there “are contrived scenes in which newbie firefighters share gum, and moments of pure cheese involving an adorable moppet and a prayer candle”.

37. She Will

Horror

Directed by the artist Charlotte Colbert, She Will sits “somewhere between a feminist revenge horror and an arthouse psychodrama”, said Ed Potton in The Times. Alice Krige plays Veronica, a faded film star, who travels to a country house retreat in the Highlands to recover from a double mastectomy. She’s hoping that it will be a peaceful idyll; instead, it teems with self-help groupies who are in thrall to the house’s flamboyant artist-in-residence (played by Rupert Everett). He likes to pee against trees and says things like, “Don’t draw the landscape, let the landscape draw you”. To escape all this, Veronica retires to her quarters, but she soon starts to sense the presence of spirits that haunt the local forest – the site of 18th century witch-burnings – and which help her wreak vengeance on a director (Malcolm McDowell) who abused her in her youth.

Krige’s “thrillingly intense” performance is the “lightning rod at the core” of this “viscerally atmospheric” drama, said Mark Kermode in The Observer. She grounds its “hallucinogenic visuals in the terra firma of past tragedies and modern traumas”. Not everything lands – some of the tonal shifts feel abrupt, and the plot can be wilfully obscure – but “these are minor imperfections” in what is a satisfyingly “chilling tale of buried secrets and dreamy vengeance”. Executive produced by Dario Argento, the film wants to be an “artfully lurid” feminist horror freak-out, said Alistair Harkness in The Scotsman; unfortunately, I found it “laughably bad”, with a “dramatically inert” script and tiresome use of “a generic Scottish setting as an off-the-peg signifier of folkloric dread”.

38. McEnroe

Documentary

Decent sports documentaries are “ten a penny”, said Wendy Ide in The Observer, but ones that really delve into “the psychology of their subject” are rare. This film, about the tennis maverick John McEnroe, is one of these rarities. Using archive material, interviews and often “unwieldy” graphics, it explores “the experience of being a phenomenon and a hate figure for a kid who was barely out of his teens” when he exploded onto the tennis scene in 1977. The result is an excellent film that deserves to find “an audience far beyond just fans of the game itself”.

This portrait of the enfant terrible of tennis is “refreshingly free of the sycophancy that drags down” most sports docs, said Ed Potton in The Times. Its appreciation for McEnroe is clear, but “tempered with an awareness of his flaws”. Among the interviewees are McEnroe’s greatest rival Björn Borg, “whose early retirement McEnroe calls an ‘absolute f***ing tragedy’”; Keith Richards, “one of several celebrity mates” who appear; and McEnroe’s second wife, Patty Smyth, who suggests that he is on the autism spectrum. “There’s only one star, though, and he’s candid, insightful and hugely likeable.”

As a result, many of the film’s most eye-opening comments come from McEnroe himself, said Raphael Abraham in the Financial Times. (“Thirty-seven psychologists and psychiatrists didn’t help,” he snarls at one point.) Still, there are omissions: the film doesn’t delve deeply enough into McEnroe’s “technical brilliance” to satisfy the “tennis nerds”, and perhaps tellingly, we hear nothing at all from his first wife, Tatum O’Neal, or his nemesis, Jimmy Connors.

39. The Railway Children Return

Drama

“Fifty-two years after setting the high watermark for ineffably wholesome family entertainment, the railway children are back,” said Kevin Maher in The Times. “And they haven’t changed a bit.” Yes, the era has shifted from 1905 – when the book and Lionel Jeffries’ much-loved 1970 film were both set – to 1944, but the characters are “reassuringly familiar”: three earnest siblings fond of outdoorsy japes find themselves evacuated from Salford to a village in Yorkshire. There, they are taken in by headteacher Annie (Sheridan Smith) and her mother Bobbie, who was the oldest of the original trio and is once again played by Jenny Agutter. There are attempts to make it more relevant to a modern audience – the siblings befriend a black GI (Kenneth Aikens) who has run away from his US army base to escape its violent racism – but the film’s appeal lies in its “unapologetic embrace” of old-fashioned storytelling. “Pixar and Marvel devotees will possibly be repulsed, but how could you not love conker fights, piggybacks on the common and a race-to-the-train finale?”

The young cast “give it their all”, and it’s a “nostalgic joy” to see Agutter return as a “distinctly glamorous grandmother”, said Matthew Bond in The Mail on Sunday. But alas, she is not on screen for all that long, and none of the actors can save the film from its “slightly opportunistic, made-for-television air”. Those who, like me, regard the 1970 film with “unalloyed affection” will be nervous about this sequel, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail. But they shouldn’t worry: the film doesn’t quite capture the original’s “charm and innocence”, but it “makes sumptuous use” of many of the same locations, and is a “lovely celebration of an England and a brand of Englishness” that still lingers.

40. Thor: Love and Thunder

Comedy

Taika Waititi has done it, said Tom Shone in The Sunday Times: he’s made “not just the best Marvel movie” to date, “but a bona fide camp comedy classic”, brimming with “gaudy” pleasures. The film, which is the fourth standalone Thor movie in the now 29-strong Marvel franchise, begins with a “helpful recap” that explains how the God of Thunder (Chris Hemsworth) picked himself up and transformed his “bad bod to a god bod” following the death of “just about everyone he ever knew”. But though his pecs are now sharp, all is not well: Thor’s beloved ex (Natalie Portman) has cancer, and a “bald creep” played by Christian Bale is plotting to murder every god in the realm. The plot is “the usual lunatic babble” we’ve come to expect from Marvel, but the story unfolds with such wit and brio, who cares? This is just the kind of “silly summer movie we didn’t know we needed”.

Steady on, said Charlotte O’Sullivan in the London Evening Standard. This “intergalactic space adventure has a bitty first half”, and isn’t a patch on the last Marvel movie that Waititi directed, 2017’s Thor Ragnarok, which is widely deemed “one of the best superhero romps ever made”. Still, fans of the genre will find a “whole lot to love” here, including some memorable performances. Look out in particular for Russell Crowe, who plays Zeus as “a cheesily Greek pansexual” with an accent straight out of Mamma Mia!. I enjoyed the film immensely, said Ed Potton in The Times. It’s true that it lacks the “irreverent zing” of Ragnarok, but it “bursts with surreal spectacle” and “Pythonesque silliness”. The “twinkly script” is genuinely funny, and though Waititi has been made to churn out the mandatory CGI battle sequences, he manages to give even them some emotional depth.

41. Turning Red

Animation

“It’s hard to know what’s more impressive about the latest Pixar film,” said Robbie Collin in The Daily Telegraph, “its boundless artistry, ingenuity and loopy comic verve, or the mere fact that the studio got away with making it.” Directed by Domee Shi, this Disney+ animation looks squarely at female puberty, “with all the distinct bodily changes” it entails. Its heroine is Mei, a 13-year-old from Toronto (“winningly voiced” by Rosalie Chiang), who wakes up one day to find she’s turned into a giant red panda. Hearing her cry out in the bathroom, Mei’s mother (Sandra Oh) assumes she’s got her period and asks enigmatically outside the door, “Did the red peony bloom?” In fact, Mei has developed a “secret family trait”: at moments of “heightened emotion”, she becomes a bear. From there, the film explores the onset of Mei’s puberty sensitively and playfully, as she strives to bring her “furry alter ego” under control in time for her to attend a concert by her favourite boy band.

Turning Red deserves credit “for finding comically direct ways to address the biological and emotional awkwardness of female adolescence in a family film”, said Alistair Harkness in The Scotsman. Usually, it’s a topic relegated to horror. But once Mei has learnt to control her panda self, the film doesn’t seem to know where to go, and it ends up feeling lazy and familiar.

“Yes, there’s a formula at work here” and the dialogue can be a bit trite, said Kevin Maher in The Times. “But who doesn’t enjoy an exquisitely manipulated cry?” With a premise like this, the film could have been “awful and preachy, like a woke revamp of Disney’s actual 1946 public information cartoon, The Story of Menstruation”. In fact, it is “ingenious and light, and deeply lovely”.

42. Boiling Point

Drama

I realise it’s early days, but “if a more stressful film” than Boiling Point comes along this year, “I would be most surprised”, said Deborah Ross in The Spectator. Filmed in a single continuous take, it stars that “powerhouse” of an actor Stephen Graham as Andy, the head chef and part-owner of a hot London restaurant. Andy’s staff “respect and like him”, but we can see something “broken” about him, “and are on it, asking ourselves: ‘Can he hold it together, or will he implode? That water bottle he is always clutching. Is it water?’”

Jangling with nervous energy, Andy tries to get on with his work, but his customers don’t help: there’s a racist table, a trio of influencers who insist on ordering off-menu, a woman with a severe nut allergy (“hello, Chekhov’s gun”), and a poisonous celebrity chef (Jason Flemyng) who demands a ramekin of za’atar to go with his risotto; it’s “98% there”, he tells the chef. With an improvised feel, the film is as “tense as a thriller”.

It’s to director Philip Barantini’s credit that I frequently forgot I was watching a one-shot film, said Mark Kermode in The Observer. It is “utterly immersive, conjuring the raw experience of an inexorably accelerating panic attack”. But like the 2015 German thriller Victoria, which was also filmed in one take, this is “first and foremost a gripping and gritty drama”.

Graham is superb as a man on the edge, said Tim Robey in The Daily Telegraph, but there is “great, frazzled acting” from the supporting cast too, especially Vinette Robinson, who plays an overburdened sous-chef. The one off-note is the ending, which tries to make a “hard-hitting impact” but doesn’t quite succeed. That aside, this is a brilliant film that exerts a remorseless grip.

43. Top Gun: Maverick

Action

The original Top Gun propelled Tom Cruise from “a heart-throb to a household name”, said Robbie Collin in The Daily Telegraph. With this “absurdly entertaining” late sequel, we have possibly the “Cruisiest” film to date. Within moments of the opening credits, Maverick – Cruise’s charismatic fictional fighter pilot – is recalled to his “old Top Gun stomping ground” to train a new generation of aviators who have assembled for a deadly mission: the neutralisation of a uranium enrichment plant in an unspecified location overseas. Among the youngsters is Rooster (Miles Teller), the son of Maverick’s friend Goose, who died in the first film. For my money, this is the best studio action movie since 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road; it is also “Dad Cinema at its eye-crinkling apogee – all rugged wistfulness and rough-and-tumble comradeship”, interspersed with flight sequences “so preposterously exciting” that they seem to invert the cinema “through 180 degrees”.

This film isn’t short of “rock’n’roll fighter-pilot action”, said Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian, but weirdly, it has none of the original’s “homoerotic tension”. “Where, oh where, is the towel round-the-waist, semi-nude locker-room intensity between the guys?” Weirder still, it’s even “less progressive on gender issues” than the 1986 blockbuster, which did at least put a woman in charge (Kelly McGillis’s civilian instructor).

It’s true, the female roles here are pretty thankless, said Clarisse Loughrey on The Independent, but the film is so “damned fun” you forget to care. Director Joseph Kosinski has made “the kind of edge-of-your-seat, fist-pumping spectacular that can unite an entire room full of strangers sitting in the dark, and leave them with a wistful tear in their eye” to boot.

44. Licorice Pizza

Drama

Licorice Pizza is the “metaphorical shot in the arm we all need right now, to go with the real one”, said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail. Paul Thomas Anderson’s “irresistible” film brims with “effervescent charm” and “belly laughs”; “I cherished every minute of it.” Set in California in 1973, the film is a “boy-meets-girl-at-high-school” tale, but the twist is that only one of the lovers is at school. That’s 15-year-old Gary (Cooper Hoffman), a child actor who falls for a 25-year-old photographer’s assistant, Alana (Alana Haim) when she visits his school to take the pupils’ pictures.

Shot on rich and grainy 35mm film, Licorice Pizza “does a superb job” of recreating 1970s Los Angeles, said Geoffrey Macnab in The i Paper. Hoffman has the same “shambling charm and force of personality” as his father, the late Philip Seymour Hoffman, while Haim – better known as a musician – brings an ingratiating spikiness to her role as the “(slightly) older woman who can’t quite believe she is falling for a teenager”. The narrative style is “deliberately rambling”, with the story unfolding in loosely joined episodes, but the result is so subversive and funny that you forgive its “shaggy-dog approach to storytelling”.

I’m afraid I found the episodic structure rather “gruelling”, said Kevin Maher in The Times. Anderson is “far too gifted to make a stinker”, but the film isn’t a patch on his better films, such as There Will Be Blood and The Master. While the love story is meant to be “adorable, cute and cuddly”, to me it seemed contrived. Alana articulates one of the film’s central flaws when she asks her sister: “Is it weird that I hang out with Gary and his 15-year-old friends?” The answer, as the characters are presented here, is: “yes”.

45. Belfast

Drama

“Kenneth Branagh has made a masterpiece,” said Kevin Maher in The Times. Belfast, set in the city in 1969, is a “deeply soulful portrait of a family in peril”, inspired by Branagh’s own childhood: his family fled to Reading that year, when he was nine. The film stars Jude Hill as Buddy, a Protestant growing up in a “warm and garrulous family”, whose carefree childhood is shattered when a “loyalist mob” rampages through their peaceful, largely Protestant community, “smashing windows and screaming: ‘Catholics out!”’ A loyalist enforcer then demands that Buddy’s father (Jamie Dornan) either “join the Catholic-bashing or face terrifying retribution”, setting the stage for a coming-of-age drama that, though not without cliché, is overlaid with dread and “an expectation of physical conflict”. Highlights of the film include a “hugely charismatic turn” from Dornan, and Haris Zambarloukos’s mostly black-and-white cinematography, which manages “to out-Roma Roma in frame after frame of meticulously lit gob-smackers”.

The film does tip into the nostalgic: at times it feels like a mash-up of Cinema Paradiso and Hope and Glory, said Deborah Ross in The Spectator – but it’s so “heartfelt, warm and authentic” that you forgive it. I welled up at least three times; plus there are some very funny lines, many of them delivered by Buddy’s grandparents (Judi Dench and Ciarán Hinds). “For some people, perhaps, the seam of sentimentality that runs through the picture might be too much,” said Brian Viner in the Daily Mail. “But it will take a stony heart not to embrace it.” The film has a “wonderful” score by Van Morrison and – an added bonus – it is relatively short, at just over an hour and a half.

46. Cow

Documentary

“Have you ever looked a cow in the eye?” If you watch Andrea Arnold’s documentary, “you certainly will”, said Clarisse Loughrey in The Independent. Shot over four years on a dairy farm in Kent, this surprisingly gripping, largely wordless film allocates much of its 94-minute runtime to a Holstein-Friesian called Luma. We watch her give birth. We watch her chew cud. We watch her get “hooked up to a milking machine, its nozzles splayed out like the heads of hungry leeches” – and then “we watch those processes again. More birth; more milk.” The film is “grimy and unvarnished”; it captures the “banal cruelty” inflicted on dairy cows – but there are moments of poetry, too: “at one point, Arnold even catches Luma gazing dreamily up towards the stars”.

“This is certainly not the first film to make the point that industrial farming and animal welfare are uneasy bedfellows,” said Wendy Ide in The Observer. Yet this “important” documentary “encourages an intimacy and emotional connection with its bovine subject that is rarely achieved elsewhere”. Shots have a “handheld urgency, the lens positioned at udder and eye level”; tellingly, it’s a good 45 minutes before we “even glimpse a blade of grass”. It’s a bleak film, and a challenging one, said Deborah Ross in The Spectator. Why would I watch a cow for 94 minutes? “What does this cow do that’s so interesting?” But you end up caring, and the finale, when it comes, is hard to bear. The trouble is, vegans already know about industrial dairy farming, and the rest won’t seek out this film, because they prefer to look away. All I can say is that the “next time I went to put milk in my tea, I did feel Luma’s big eyes upon me. So it is absolutely haunting in that way.”

47. Minions: The Rise of Gru

Animation