Welcome to the metaverse

The metaverse, a virtual reality-powered version of the internet, is Silicon Valley’s new obsession. Could it change the world?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Where did the idea originate?

From science fiction. In Snow Crash, a cult 1992 sci-fi novel by Neal Stephenson, the metaverse is a 3D virtual reality world where people can go to escape a dystopian reality: a vast online game in which people’s avatars wander around interacting with one another, accessing online services, going to virtual night clubs, and getting into virtual sword fights. Tech firms use the term today to mean different things, but at its most basic it refers to virtual spaces where you can collaborate and socialise with other people who aren’t in the same physical space as you. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief executive, describes the metaverse as “an internet you’re inside of, rather than just looking at”.

Why is the metaverse in the news?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It hit the headlines in July, when Zuckerberg declared that in the next five years, “I expect people will transition from seeing [Facebook] primarily as a social media company to seeing us as a metaverse company”. Facebook already owns Oculus, a leading manufacturer of virtual reality headsets. It is also developing Horizon Workrooms: these are virtual meeting rooms for up to 50 people where, using Oculus headsets, you and your colleagues’ cartoony avatars can gather, talk and gesticulate. More ambitious still is Horizon Worlds, a virtual world which is part social network and part gaming platform, inside which users can meet, play games and also create new game worlds. In the future, says Zuckerberg, “you’re basically going to be able to do everything that you can on the internet today as well as some things that don’t make sense on the internet today, like dancing”. As part of its strategy to build a metaverse, Facebook announced that it will be creating 10,000 jobs in the EU over the next five years. The tech giant will hire high-skilled engineers in countries across the bloc and focus its recruitment drive on Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Poland, the Netherlands and Ireland, CNBC reported.

Hasn’t all this been hyped before?

Online worlds have been around for several decades, and Second Life, launched in 2003, was talked up at the time as a step towards a Matrix-style virtual reality. Some of today’s biggest online games, such as Fortnite, Roblox and Minecraft, already have many metaverse-like features. Enthusiasts point to a virtual concert by the electronic musician Marshmello staged inside Fortnite in 2019, attended by ten million players.

However, the technology is now opening up new avenues, in terms of both virtual and “augmented” reality: Facebook hopes that its new smartglasses will put a whole computing universe in front of your eyes, melding real and digital worlds. Just as smartphones transferred the internet from our desks to our pockets, with all sorts of knock-on effects on business and society, so, it is argued, new platforms will again change the way we live our lives. The metaverse, explains The Verge, a technology blog, is “partly a dream for the future”, and partly a way of encapsulating changes that are already under way.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How long will it take?

“Many of these products will only be fully realised in the next ten to 15 years,” says Andrew Bosworth, who runs Facebook Reality Labs. There are lots of technical hurdles to overcome if you want to get a Snow Crash-style online world up and running. Besides huge inputs of raw computing power and lots of virtual reality headsets, a working metaverse will require innovations in everything from broadband networks to software protocols. The holy grail is that virtual worlds should feel “persistent” (i.e. they don’t freeze or end); should offer a feeling of genuine “presence” in the virtual world; and should provide “interoperability” of data and digital assets.

What is interoperability?

The ability of different computer systems to work together, as they do on the web. At the moment, tech brands often don’t let their properties intermingle: Microsoft Xbox owners can’t usually play online games with a Sony PlayStation owner. However, the popularity of metaverse-ish games such as Fortnite has meant that Microsoft and Sony have had to bend the rules. Fortnite is also one of the few places where rival intellectual property brands – Batman and Star Wars, say – are licensed to mix. These are the kinds of developments that proponents of the metaverse want to see happening everywhere. The idea is that all your digital possessions ought to be portable across different platforms, perhaps through the use of non-fungible tokens, aka NFTs. “If you buy a virtual shirt in Metaverse Platform A,” The Verge explains, you should be able to “redeem the same shirt in Metaverse Platforms B to Z.”

How will it change your life if you don’t play video games?

Thanks to the pandemic, we’re nearly all familiar with the notion of working and socialising online, and with the limitations of video platforms such as Zoom. In theory, the metaverse offers massive improvements on all this. Throw in a fully functioning digital economy in which users can buy – and be paid for creating – stuff inside the world, and it’s a tech-futuristic dream or nightmare, according to taste. Its advocates enthuse about its mind-blowing possibilities, and its economic opportunities. Critics see it as a blueprint for “virtual reality with unskippable ads”. Either way, big brands are already pondering their metaverse strategies.

What’s in it for Facebook?

Obviously, it wants to be at the tech cutting edge, and with more users and user-generated content than any other platform in the world, it is well-placed to navigate a metaverse-shaped future. At the same time, Facebook’s army of lobbyists is keen to massage its battered reputation. Cynics suggest that rebranding itself as a “metaverse company” allows Facebook to dissociate itself from the woes of social media, and to distract from its battles with competition authorities and regulators across the Western world. In Zuckerberg’s vision of the metaverse, suggests The Washington Post, “people could play games, exchange cryptocurrency payments, attend meetings – and, perhaps most importantly, see Facebook as cool again”.

NFTs in the metaworld

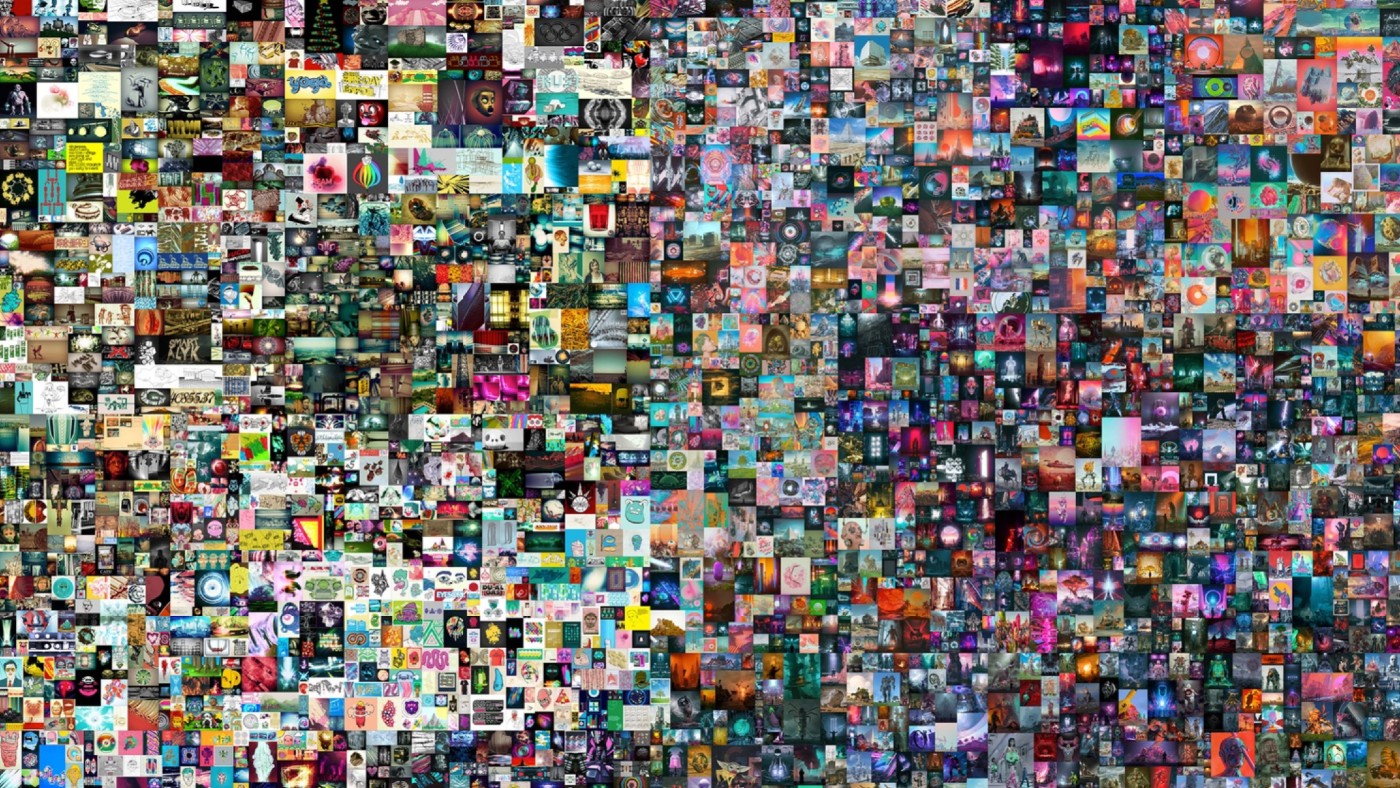

Non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, are digital certificates of ownership or authenticity. They became notorious in March when one of them, conferring rights over a digital collage by the artist known as Beeple, was sold for $69.3m at Christie’s. (The buyer was a metaverse enthusiast and cryptocurrency investor known as MetaKovan.) Like cryptocurrencies, NFTs often come up in speculations about the metaverse. Both use an underlying technology – blockchain ledgers – that does away with the need for any one company or authority to guarantee them: great for techno-libertarians and “interoperability” enthusiasts.

The best existing example of a metaverse project using NFTs is an online game called Axie Infinity, launched by a Vietnamese company in 2018. It’s a Pokémon-like trading and battling game: to play, you buy axies, axolotl-like creatures, digitised as NFTs. If you do well breeding and fighting them, you amass an in-game currency that can be exchanged for a cryptocurrency. Forbes reports that people in the developing world – mainly the Philippines – “are playing Axie Infinity as their main source of income in areas where banking services are hard to access and often expensive”. The game has an annual revenue of around $1.5bn.