Coronavirus: who should be released from lockdown first?

Economics experts on why low risk millennials should be first out of lockdown

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Nattavudh Powdthavee, professor of behavioural economics at Warwick Business School, University of Warwick, and Andrew Oswald, professor of economics and behavioural science at University of Warwick, discuss who should be released from lockdown first - and why.

Millennials who do not live with their parents should be the first people released from the UK coronavirus lockdown. That is the conclusion of our new research which is being studied in Whitehall by officials. The move would be one part of a possible exit strategy the government could implement in the coming weeks and months.

We came to this conclusion because people aged between 20 and 30 are statistically the safest from COVID-19 among the age groups. They are also the hardest hit financially from the prolonged lockdown. Getting them back into work could help restart the economy and increase their own prosperity.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Releasing millennials from lockdown first would mean they could provide essential supports for the rest of society, particularly those in the high risk groups, such as the elderly or those with underlying conditions.

It could also be argued that giving this generation a strong leadership role to help the nation find its way out of the crisis could provide hope to the rest of the country.

According to the Office of National Statistics, there are about 4.2 million people aged between 20 and 30 who do not live with parents. Of those, 2.6 million are private sector workers who may have lost their earnings entirely because of the lockdown. If half of those could be re-employed by private sector when they are the first to be released, then the extra annual income generated would be about £13 billion a year.

How many would die?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But in doing this, there is obviously the questions about how many young deaths society would have to tolerate. Based on a standard epidemiological model, the fatality risk associated with the release of these young people has been estimated to be at around three in 10,000. By way of comparison, the fatality risk is about 75 times higher for those in their 60s. If, for example, half of the 4.2 million young people were infected, then the extra premature deaths in the United Kingdom would be 630.

While we fully recognise that any loss of life – however few – is tragic, we believe that a policy that releases the young from the lockdown first will produce a number of fatalities that is far smaller in the long run than those from any general release of the population. Older adults who have been tested to have the necessary antibody can then be released later in a staggered way.

Understandably there would be many people who are opposed to the idea of releasing the young first. To these people, the small fatality risk associated with Covid-19 weighs much more heavily in their minds compared to other less salient fatality risks such as those associated with poverty and unemployment. Because of this, many people would likely prefer that the state lockdown be extended until a vaccine is found. But this could be up to 18 months away.

Knowing all the risks

Efforts would have to be made by politicians and others to explain all the risks to the general public. Here, a useful lesson could be learned from research on risk literacy, which is the ability to deal with uncertainties in an informed way.

For example, according to a 2012 study, there was a sudden surge in the number of accident-related deaths on American roads, as people sought alternative transport to flying, one year after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001. An estimated 1,600 more people died as a result of a significant increase in traffic than would have been expected statistically. By contrast, there had been no fatalities from commercial flights in the United States during the same period.

The explanation for the findings may be obvious: flying is substantially less risky than driving a long distance. Yet, the fear of immediate death from a terrorist attack had altered the behaviour of many Americans, which had led to a significantly greater number of deaths than had they chosen to fly.

The fatality risk associated with road accidents is not so different from the fatality risk associated with economic inactivity for the young if the lockdown goes on for too long. Compared to the small risk of the young dying from contracting COVID-19, the long term fatality risk from poverty and unemployment for the young is much more substantial but likely to be less prominent in people’s mind.

For such a step to be successful, it is vital that all of the associated risks are made clear and transparent to everyone. Unless a vaccine is suddenly discovered, any decision will be difficult. The best exit strategy would be one that minimises all of the associated risks, regardless of how attention grabbing each one of them is in our mind.

Nattavudh Powdthavee, Professor of Behavioural Science, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick and Andrew Oswald, Professor of Economics, University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

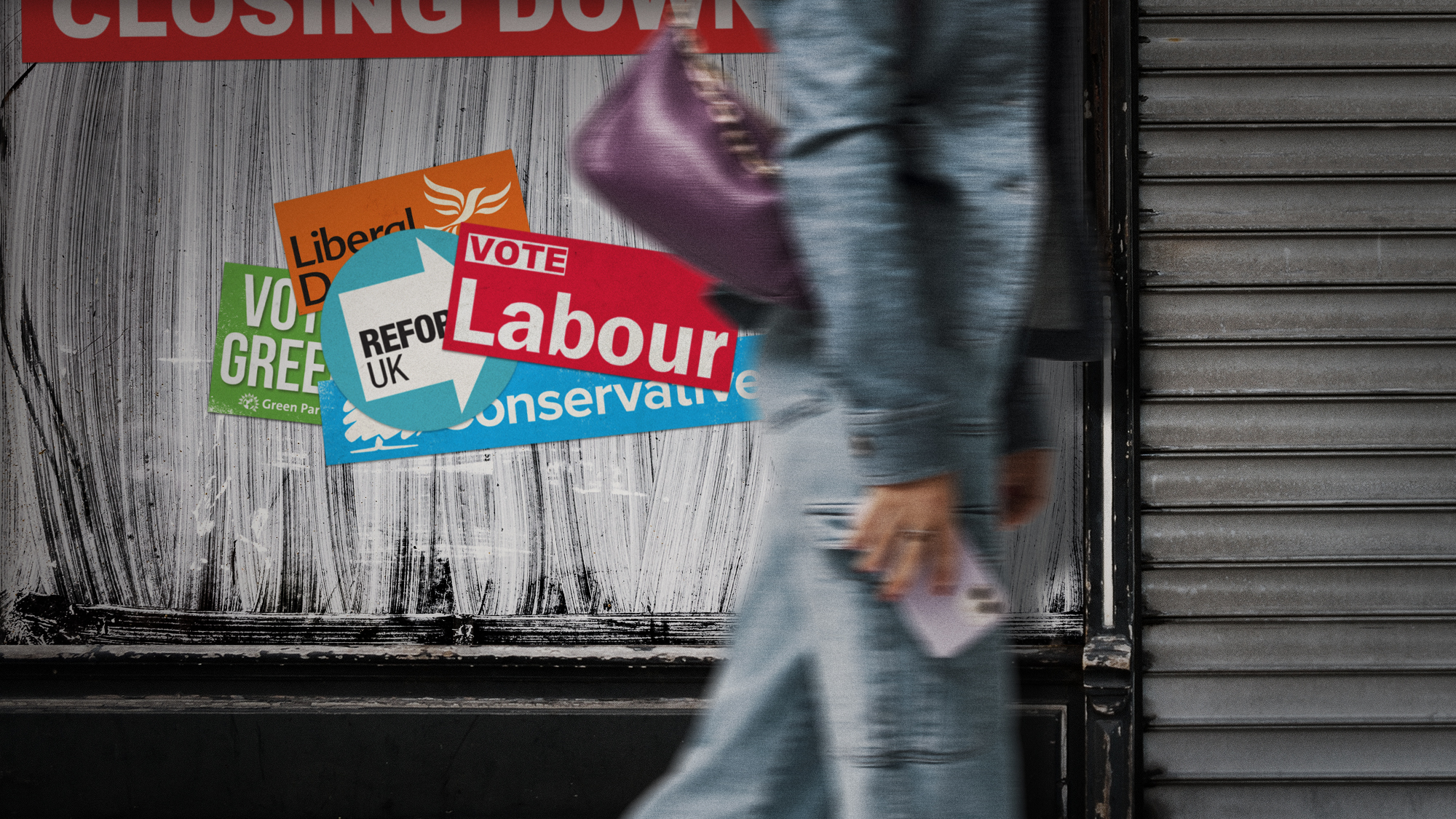

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?Today's Big Question Europe's two biggest economies sign first treaty since WWII, underscoring 'triangle alliance' with France amid growing Russian threat and US distance

-

Is the G7 still relevant?

Is the G7 still relevant?Talking Point Donald Trump's early departure cast a shadow over this week's meeting of the world's major democracies

-

Angela Rayner: Labour's next leader?

Angela Rayner: Labour's next leader?Today's Big Question A leaked memo has sparked speculation that the deputy PM is positioning herself as the left-of-centre alternative to Keir Starmer

-

Is Starmer's plan to send migrants overseas Rwanda 2.0?

Is Starmer's plan to send migrants overseas Rwanda 2.0?Today's Big Question Failed asylum seekers could be removed to Balkan nations under new government plans