The photos we don't see

What if images of mass shooting victims were published?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When former police officer Stephen Spainhouer rushed to the scene of a mass shooting at an Allen, Texas, outlet mall last week, he came upon a battlefield. Bloody, torn bodies were scattered on the ground next to the dead killer and his assault rifle. A little girl seemed to be hiding next to a bush, but when Spainhouer turned her over, "she had no face." He tried performing CPR on other victims, but "the injuries were so severe there was nothing I could do." Hours later, cellphone images of the disfigured dead began circulating on Twitter. No mainstream publication, including this one, would publish such photos, for many reasons: the need for family consent; preserving the dignity of the dead; the sensibilities of readers. But by not showing what mass shooters do to human beings, do we make it easier to be numbed to the slaughter? If Americans were repeatedly exposed to images of children with their faces blown off, would they still accept that "nothing can be done?"

Images have great power; they can reach into hearts and minds in a way words often do not. When Emmett Till's mother allowed publication of photos of her late son's mutilated face in 1955, the revulsion galvanized the civil rights movement. Other photos have also marked turning points in history: the 1972 image of a naked, 9-year-old Vietnamese girl burned by U.S. napalm; the 2004 photos of Iraqis humiliated and tortured by U.S. soldiers at the Abu Ghraib prison; the video of a police officer with his knee on the neck of a pleading, dying George Floyd. What if we'd seen what an assault rifle did to the 20 first-graders and six adults in Newtown? (Some of their bodies had to be identified by DNA.) Or the 19 kids and two teachers methodically executed in Uvalde? Or the 26 churchgoers massacred in the pews at Sutherland Springs? Would their gruesome deaths still be written off as the regrettable but necessary price of "freedom"?

This is the editor's letter in the current issue of The Week magazine.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

William Falk is editor-in-chief of The Week, and has held that role since the magazine's first issue in 2001. He has previously been a reporter, columnist, and editor at the Gannett Westchester Newspapers and at Newsday, where he was part of two reporting teams that won Pulitzer Prizes.

-

Political cartoons for February 7

Political cartoons for February 7Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an earthquake warning, Washington Post Mortem, and more

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shooting

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shootingSpeed Read Police did not share the identities of the officers or the slain suspect, nor the motive or the focus of the still-active investigation

-

Trump lambasts crime, but his administration is cutting gun violence prevention

Trump lambasts crime, but his administration is cutting gun violence preventionThe Explainer The DOJ has canceled at least $500 million in public safety grants

-

Aimee Betro: the Wisconsin woman who came to Birmingham to kill

Aimee Betro: the Wisconsin woman who came to Birmingham to killIn the Spotlight US hitwoman wore a niqab in online lover's revenge plot

-

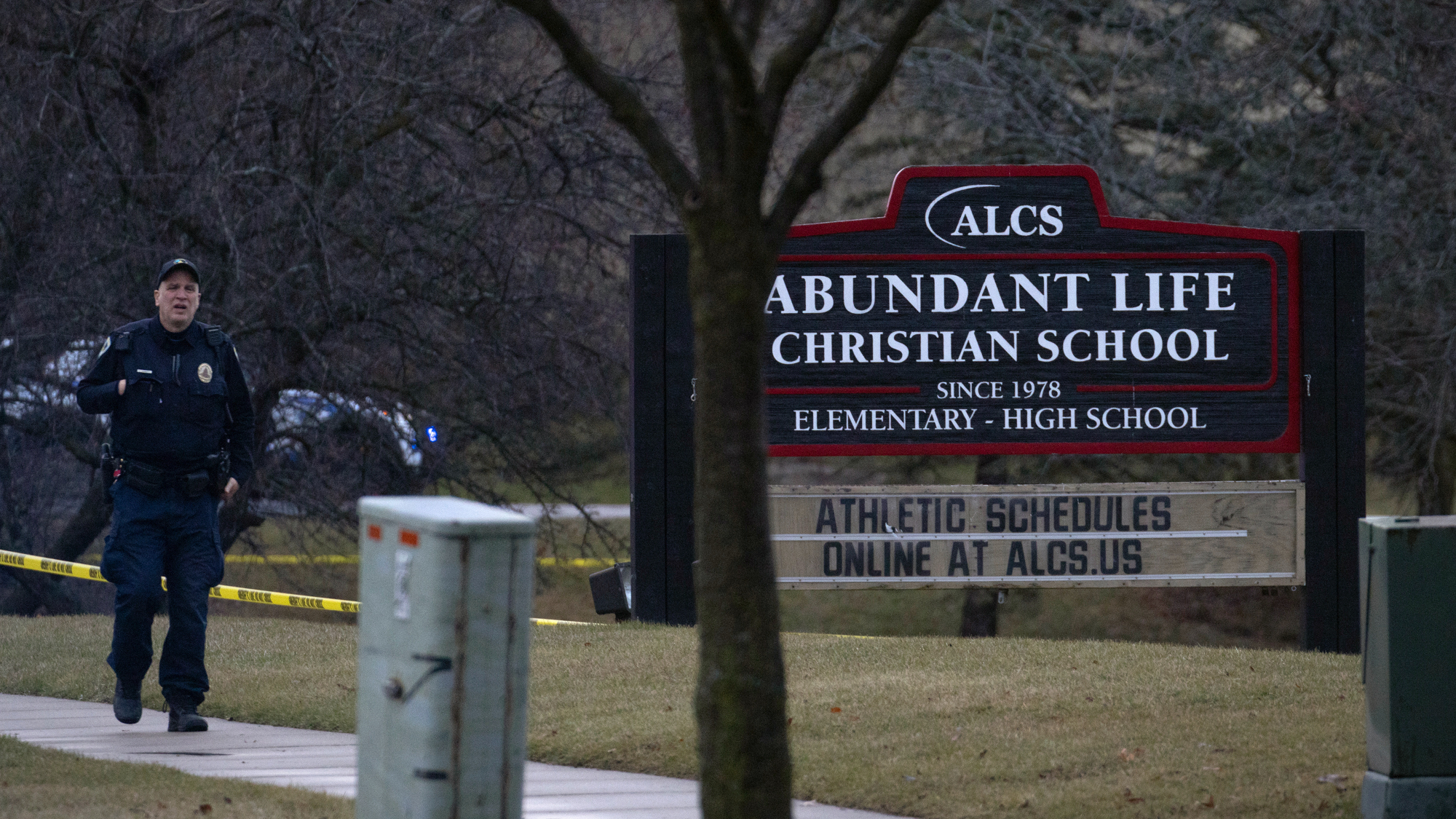

Teenage girl kills 2 in Wisconsin school shooting

Teenage girl kills 2 in Wisconsin school shootingSpeed Read 15-year-old Natalie Rupnow fatally shot a teacher and student at Abundant Life Christian School

-

Father of alleged Georgia school shooter arrested

Father of alleged Georgia school shooter arrestedSpeed Read The 14-year-old's father was arrested in connection with the deaths of two teachers and two students

-

Unlicensed dealers and black market guns

Unlicensed dealers and black market gunsSpeed Read 68,000 illegally trafficked guns were sold in a five year period, said ATF

-

Michigan shooter's dad guilty of manslaughter

Michigan shooter's dad guilty of manslaughterspeed read James Crumbley failed to prevent his son from killing four students at Oxford High School in 2021

-

Shooting at Chiefs victory rally kills 1, injures 21

Shooting at Chiefs victory rally kills 1, injures 21Speed Read Gunfire broke out at the Kansas City Chiefs' Super Bowl victory parade in Missouri