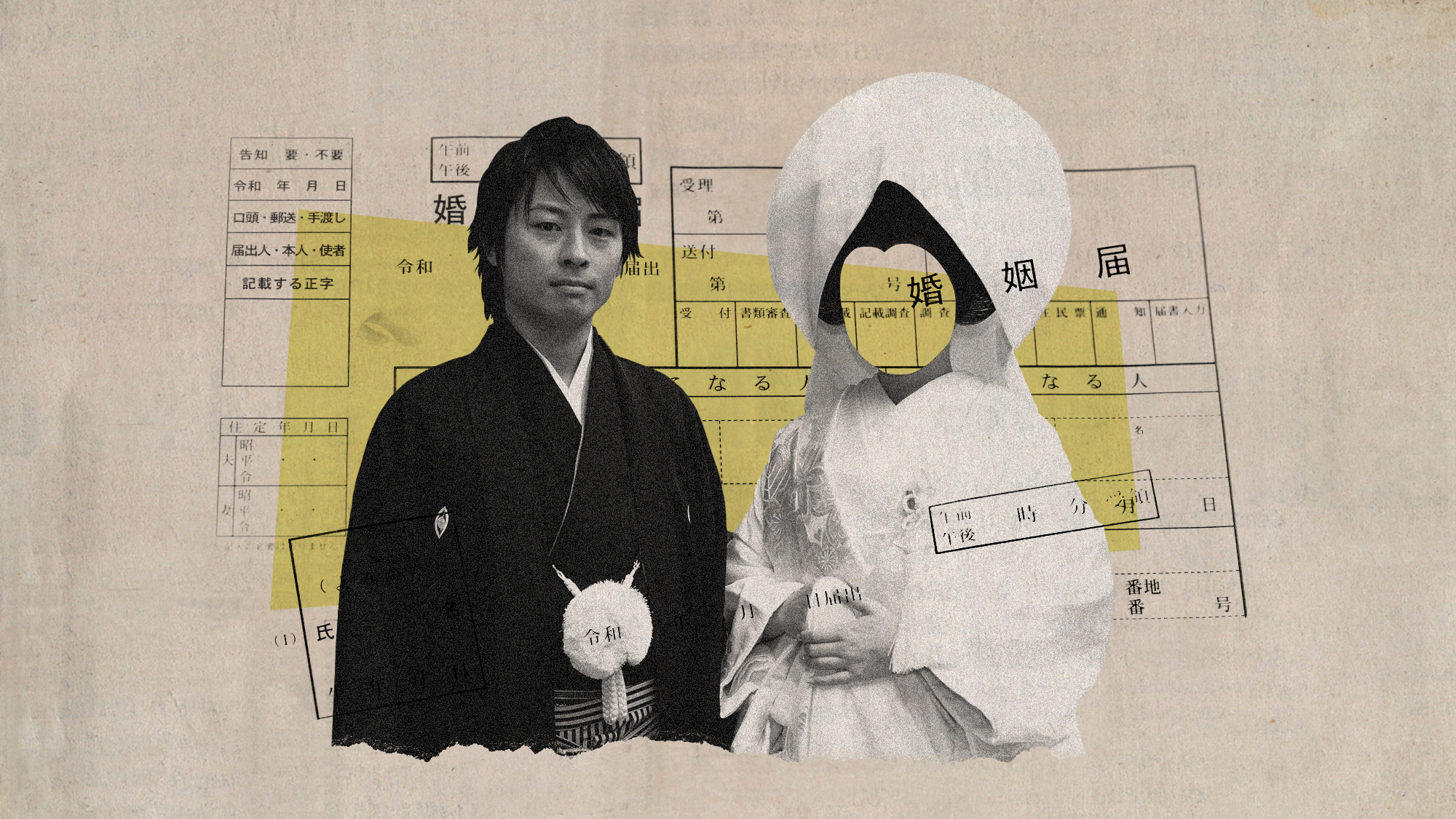

Japan's surname conundrum

Law requiring couples to share one surname hinders women in the workplace and lowers birth rate, campaigners claim

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It is a question many couples wrestle with when getting married. Do they take their partner's surname or keep their own?

But while it is common in many countries for couples to take a single surname after marriage, in Japan it is a legal requirement. The law, dating from Japan's Meiji era, which ended in 1912, does not explicitly state that a woman must take her husband's name, rather than a man taking his wife's, but 95% of women do.

'A human rights issue'

Japan's largest business lobby, Keidanren, has said the law "hinders women's advancement".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As women "rise in the workplace" the status quo is causing "resentment", said The Economist. "Name changes are a pain for people who have toiled to build a strong reputation" and while using one for legal documents and another for work is "doable", it "invites confusion".

It is also claimed that the law contributes, in part, to Japan's low birth rate. A survey conducted by Asuniwa, an NGO which advocates for a selective dual-surname system, reported in The Japan Times, found almost 30% of people in "de facto" marriages would legally tie the knot if the law changed. This number could be as high as 590,000 people, so in a country where having a child out of wedlock is still taboo this would lead to more births, the argument goes.

Naho Ida, head of Asuniwa, said the impact of forcing couples to share a surname should "be seen as a human rights issue".

Campaigners also say a change in the law will stop uncommon surnames from dying out, with one study suggesting that over time everyone in Japan will end up being called "Sato", the country's most common surname.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

'Confuse kids and loosen family bonds'

"Much as abortion rights have become a litmus test in American politics" so the surname requirement has "come to symbolise Japan's status on a constellation of women's rights", said The New York Times.

Polls in recent years indicate between a half and two-thirds of the public favour scrapping the law. So do many politicians.

In May, lawmakers discussed a bill put forward by opposition parties – the first time the Diet had debated the law in 28 years according to Japanese daily The Mainichi – but it was ultimately blocked by the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

The problem, said The Economist, is that reformers in the LDP are "loth to challenge the hard-right flank of their party, particularly ahead of an upper-house election in July".

"The issue has become totemic for a chunk of the Japanese political right", with conservative hardliners arguing a change in the law would "confuse kids and loosen family bonds". One speaker at a recent gathering of the ultra-conservative Nippon Kaigi group said efforts to change name rules were part of a "Communist plot" to "tear apart traditional values and destroy the country".

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriors

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriorsThe Week Recommends British Museum show offers a ‘scintillating journey’ through ‘a world of gore, power and artistic beauty’

-

Quiet divorce is sneaking up on older couples

Quiet divorce is sneaking up on older couplesThe explainer Checking out; not blowing up

-

In Okinawa, experience the more tranquil side of Japan

In Okinawa, experience the more tranquil side of JapanThe Week Recommends Find serenity on land and in the sea

-

How coupling up became cringe

How coupling up became cringeTalking Point For some younger women, going out with a man – or worse, marrying one – is distinctly uncool

-

How AI chatbots are ending marriages

How AI chatbots are ending marriagesUnder The Radar When one partner forms an intimate bond with AI it can all end in tears

-

A dreamy skiing adventure in Niseko

A dreamy skiing adventure in NisekoThe Week Recommends Light, deep, dry snow and soothing hot springs are drawing skiers to Japan’s northernmost island

-

Lavender marriage grows in generational appeal

Lavender marriage grows in generational appealIn the spotlight Millennials and Gen Z are embracing these unions to combat financial uncertainty and the rollback of LGBTQ+ rights