Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship in return for a year's service are now trapped on frontline indefinitely

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Russia is scrambling to enlist more soldiers to replace the vast numbers killed or wounded in the nearly three-year war in Ukraine.

That demand is increasingly being met by fighters from abroad, from North Korea to Africa. Thousands of foreign nationals have joined the Russian army, "lured by the promise of hefty paychecks and fast-tracked citizenship for themselves and their kin", said Politico.

In Cuba, Russia's old Cold War ally, the repressive regime, economic crisis and nationwide blackouts make the promise of a Russian passport "a major draw". But the document "comes with a noose attached": Moscow is "trapping foreigners" on the frontline.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What's the relationship between Russia and Cuba?

The ties between the two nations are political as well as economic. After Fidel Castro's Communist revolution in Cuba ended in 1959, the Soviet Union supported Havana against a US trade embargo. In the 1970s and 1980s, tens of thousands of Cubans fought in Angola alongside Russia in a proxy war against the US and its allies.

These days, Russia is Cuba's main creditor. Last year Moscow sent tankers carrying crude oil to the island to "help ease the economic slump", said Bloomberg.

Cuba also relies on Russia for wheat, and while it has remained formally neutral on the Ukraine invasion it has "publicly kowtowed to Putin", said Politico. But while Moscow's allies like Iran and North Korea have provided Russia with artillery, "impoverished Cuba has little else to offer but honeyed words" – and manpower.

According to the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the number of Russian troops killed or wounded has reached more than 800,000. While it's difficult to verify numbers, experts are "unanimous" in concluding that Russia's casualty figures are "in record numbers", said Al Jazeera: the highest since the Second World War.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So what's the appeal for Cuban fighters?

Last January, President Vladimir Putin signed a decree allowing foreigners to obtain citizenship in return for a year's service in the Russian army.

A Russian passport allows visa-free travel to 117 destinations (compared with just 61 for a Cuban one). Some Cubans hoped that enlisting would "buy them a new life", said Politico. Others say they were "hoodwinked into travelling to Russia", after responding to posts on social media for "what they thought would be low-skilled, civilian jobs".

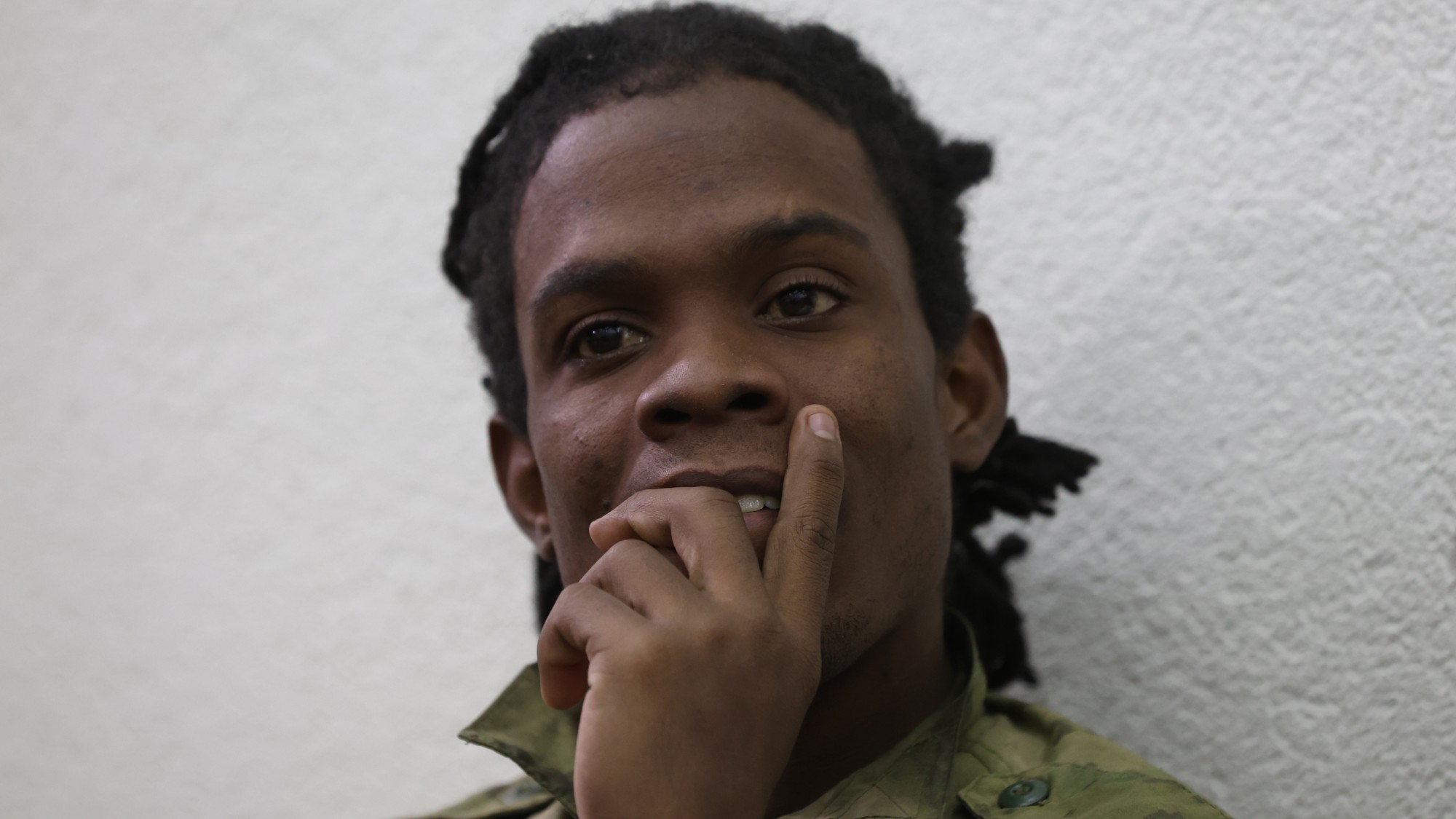

Darío Jarrosay, a 35-year-old teacher and musician, said he responded to a Facebook appeal for construction workers. "It wasn't to enter the war; I never agreed to enter the war." He was imprisoned by Ukrainian troops while fighting with Russian forces.

Russia "takes advantage of the need and desperation" in Cuba, said Arturo McFields Yescas, the former Nicaraguan ambassador to the Organization of American States. It offers $2,000 a month (the average Cuban makes only $30), Russian citizenship, and 15 days' holiday every six months, he wrote on The Hill. "This is an attractive promise that Putin has only half-fulfilled, generating desertions and discontent."

What is happening to them in Ukraine?

Reports have emerged of Cuban recruits suffering beatings, abuse and unpaid wages in the Russian army, as well as the withholding of passports. "They have not given us documents," a Cuban mercenary said in a viral video. "They keep scamming us, they keep deceiving us, we keep dying and no one does anything."

For many, Russian citizenship also turned out to be a poisoned chalice. As "newly minted Russians", Cuban recruits – even if they only signed up for a one-year stint in the army – are "no exception" to Russia's mass mobilisation, said Politico.

"Now they're telling us that, since we're Russian citizens, we have to continue fighting until the end of the war," said one Cuban.

What is Cuba's position?

Cuba forbids its citizens to fight abroad for personal benefit – with the threat of hefty jail sentences or even capital punishment. But Havana has sent "contradictory signals" over citizens' involvement in Ukraine, said Bloomberg.

After reports emerged of hundreds of Cubans fighting in 2023, Cuba's ambassador to Russia said Havana did not object to its citizens joining the Russian army. But "hours later", Cuba's foreign ministry said Havana's "unequivocal" position was to oppose any involvement. "Cuba is not part of the war in Ukraine," it said in a statement.

The predicament of Cuban fighters was "further complicated" by an announcement that Cuba would treat them as "illegal mercenaries", said CNN. For Cubans fighting on the other side of the world, "their choices now seem to be exile in a war zone, or prosecution and a lengthy jail sentence back home".

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What is ‘Arctic Sentry’ and will it deter Russia and China?

What is ‘Arctic Sentry’ and will it deter Russia and China?Today’s Big Question Nato considers joint operation and intelligence sharing in Arctic region, in face of Trump’s threats to seize Greenland for ‘protection’

-

Is the Chinese embassy a national security risk?

Is the Chinese embassy a national security risk?Today’s Big Question Keir Starmer set to approve London super-complex, despite objections from MPs and security experts

-

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?Today's Big Question Security agreement commits British and French forces in event of ceasefire

-

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?Today’s Big Question ‘Mildness’ of EU pushback against Trump provocation ‘illustrates the bind Europe finds itself in’

-

Greenland, Colombia, Cuba: where is Donald Trump eyeing up next?

Greenland, Colombia, Cuba: where is Donald Trump eyeing up next?Today's Big Question Ousting Venezuela’s leader could embolden the US administration to exert its dominance elsewhere

-

Did Trump just end the US-Europe alliance?

Did Trump just end the US-Europe alliance?Today's Big Question New US national security policy drops ‘grenade’ on Europe and should serve as ‘the mother of all wake-up calls’

-

Taiwan eyes Iron Dome-like defence against China

Taiwan eyes Iron Dome-like defence against ChinaUnder the Radar President announces historic increase in defence spending as Chinese aggression towards autonomous island escalates

-

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?Today's Big Question How best to boost troop numbers to deal with Russian threat is ‘prompting fierce and soul-searching debates’