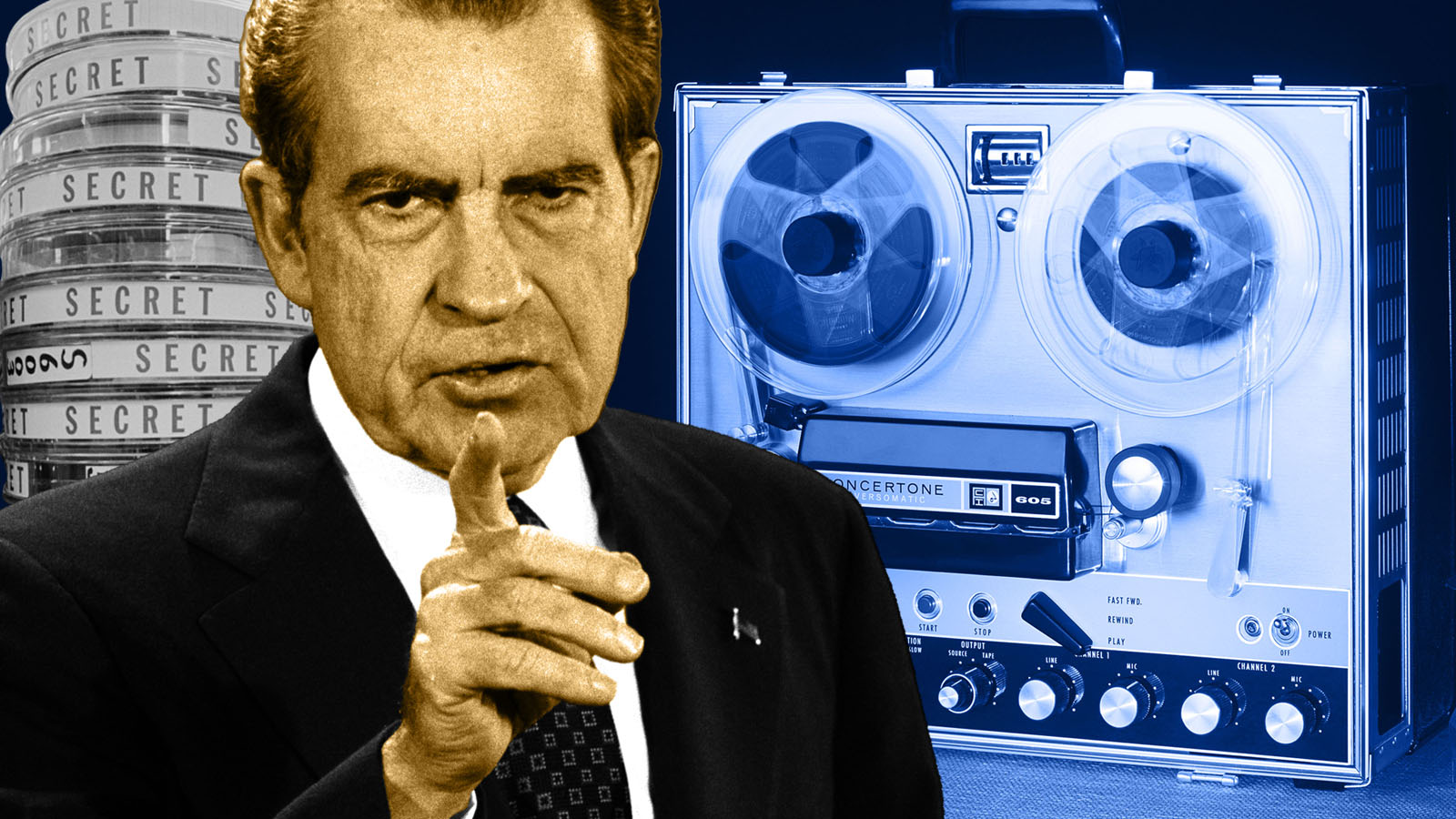

In Trump's missing texts, an echo of Nixon's 18 minutes

Is the cover-up worse than the crime?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

More texts are missing.

Last week, America learned that the Pentagon deleted text histories from the cell phones of key officials — including acting Defense Secretary Chris Miller — following the Jan. 6 insurrection. It's part of a trend: "Similar deletions of communications around Jan. 6 by the Department of Homeland Security and the Secret Service were already the subject of considerable controversy," Martin Pengelly notes at The Guardian.

Now questions are being asked. Are those departments covering up complicity in the insurrection, covering up their failures, or is the whole thing simply a big — and unfortunate — coincidence? The last option seems increasingly unlikely. "At the seniormost levels of those departments I'd have to say, it does smell, it is problematic," said former Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In politics, there is an old saying: "The cover-up is worse than the crime." In American history, one cover-up is more famous than any other, and it involves the disappearance of electronic documentation: The case of the missing 18 minutes from the Nixon White House tapes. Here's everything you need to know:

What was Watergate?

The scandal that prematurely ended Richard Nixon's presidency started on June 17, 1972, when a group of burglars was caught breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Hotel in Washington D.C. One of the burglars was soon linked to Richard Nixon's re-election campaign. For Nixon, everything went downhill from there.

Over the next two years, it emerged that the Nixon White House was a hotbed of illegal activity and power abuses. His staff had drawn up an "enemies list" with the names of hundreds of critics — including, bizarrely, singer Barbra Streisand, actor Paul Newman, and New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath — with the intent of using "the available federal machinery to screw our political enemies." His administration used the IRS to audit and harass left-leaning think tanks and journalists who had written critically of the administration. His henchmen even burglarized the office of a psychiatrist who treated Daniel Ellsberg, the whistleblower who had released the Pentagon Papers to the public.

How did the tapes come into play?

Nixon and his cronies might've gotten away with all of this, except for one thing: The White House kept a recording system that taped many of his Oval Office conversations. He wasn't the first president to do this: "Six American presidents — from Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Nixon — taped at least some of their conversations," Richard A. Moss and Luke Nichter wrote for The Washington Post in 2017. As Nixon plotted with aides to thwart the investigation into the Watergate break-in, "the plan was captured on a voice-activated taping system in a recording that came to be known as 'the smoking gun,'" Tom van der Voort writes for the Miller Center.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The existence of the taping system came to light during congressional hearings into the scandal. "Now Nixon's word could be weighed against not just those of burglars or admittedly corrupt staff members trying to protect themselves," van der Voort writes, "but also against a real-time record of events."

That was big news. Bigger news? The revelation that one key tape — an 18.5-minute section that included a conversation between Nixon and his chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman — had been erased. Nixon's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, took the blame, saying she had accidentally erased the tape while transcribing it. But the public was skeptical, to say the least. "The political reaction to the erasure eroded Nixon's already-poor credibility," Andrew Glass wrote for Politico in 2016.

How did all of this bring about Nixon's downfall?

Nixon fought against releasing the tapes, saying it was necessary to defend the principle of the "confidentiality of presidential conversations." Instead of obeying a subpoena for the tapes, the White House released more than a thousand pages of edited transcripts. That was bad enough for Nixon: "The conversations show the president discussing at length raising blackmail money," The Washington Post reported at the time. It wasn't enough for prosecutors. In June 1974, the Supreme Court ordered Nixon to surrender the tapes to investigators. Soon, the House Judiciary Committee approved articles of impeachment against Nixon. On Aug. 9, Nixon resigned from office.

The mystery of the missing 18 minutes continues to fascinate, however. John Dean, who served as Nixon's White House Counsel, doesn't believe the erasure amounted to much. "It wasn't Haldeman or Erchlichman sitting there saying, 'Oh boy, did we mess up that job where we tried to break into Watergate,'" Dean told the New York Post in 2014. "Which is the kind of thing people were fantasizing they might have been talking about." There have been efforts over the years to recover the lost recordings from the tape, but they have failed; the tape itself is the property of the National Archives. Skepticism about the erasure endures: The National Security Archive presents an annual "Rosemary Award" — named for Woods — to federal officials who demonstrate "outstandingly bad responsiveness to the public that flouts the letter and spirit of the Freedom of Information Act."

Will the lessons of Watergate mean anything to the Jan. 6 investigation? Perhaps. It's not just the texts that are missing from the public record — there is also a seven-hour gap in Donald Trump's phone logs from the day of the insurrection. In other words, a lot of records are conveniently absent. It's not the first time that's happened. "The whole history of Watergate is a Marx Brothers routine," Jill Wine-Banks, an assistant Watergate special prosecutor, told ABC News in 2017. "You have a ridiculous break-in with so many errors that they got caught red-handed and … it is absurd, and yet facts are facts."

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ire

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ireSpeed Read Trump said he will close the center for two years for ‘renovations’

-

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJ

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJSpeed Read Ed Martin lost his title as assistant attorney general

-

Gabbard faces questions on vote raid, secret complaint

Gabbard faces questions on vote raid, secret complaintSpeed Read This comes as Trump has pushed Republicans to ‘take over’ voting

-

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrum

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrumFeature His desire for Greenland has seemingly faded away

-

The price of forgiveness

The price of forgivenessFeature Trump’s unprecedented use of pardons has turned clemency into a big business.

-

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?Today's Big Question Could political pressure overcome legal obstacles and force either man to give evidence over their relationship with Jeffrey Epstein?

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities