Censoring ideas and rewriting history

Several states are banning books and criminalizing the teaching of controversial topics. What’s become verboten?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Several states are banning books and criminalizing the teaching of controversial topics. What's become verboten? Here's everything you need to know:

Is censorship growing?

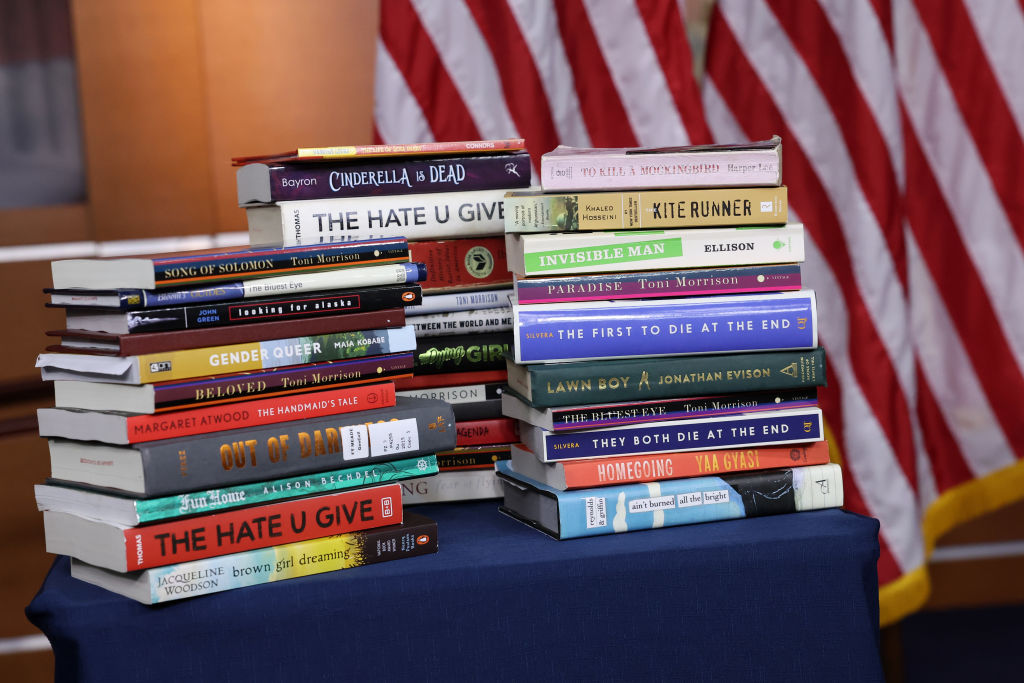

Yes. Recently passed state and local legislation is dictating what schools may or may not teach and what students may or may not read. A record 2,571 different titles were banned or censored by school districts, states and other government entities in 2022, according to the American Library Association — a 38% increase from the previous year. Nearly 60% of those bans were aimed at classrooms and school libraries, and most of the targeted books were by or about racial minorities or LGBTQ people. Broad, vaguely defined prohibitions on teaching "critical race theory" and other allegedly divisive topics in classrooms have compelled 1 in 4 U.S. teachers to alter their curricula. In Florida, a textbook publisher even had to completely remove a purely factual passage on George Floyd's murder and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests. In at least a half-dozen states, teachers and school librarians now face potential prison time for violating the bans. It isn't just individual books being "removed, restricted, suppressed in public schools" anymore, said Kasey Meehan of the PEN America foundation. "It's a set of ideas, it's themes, it's identities, it's knowledge on the history of our country."

Where is this happening?

Most of the restrictions enacted this school year have been passed by Republican-controlled legislatures in Texas, Florida, Missouri, Utah, and South Carolina. Spurred by conservative groups such as Moms for Liberty, a two-year-old organization that has helped propel hundreds of like-minded candidates onto school boards, these legislatures have passed laws with broad restrictions on topics they deem inappropriate. The mere presence of LGBTQ people in a book can be enough to merit the label "obscene." In Florida and several other states, all books must be screened by official censors before they are deemed acceptable, with wholesale bans on references to sex, race, and gender identity, regardless of context. In Missouri, a new law banning books containing "explicit sexual material" led school districts to junk art history textbooks and nonfiction accounts of the Holocaust. In Texas, which had more book bannings than any other state last year, a bill currently under consideration would ban textbooks that portray U.S. history in anything but a "positive" light. In Florida, new laws pushed by Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) have tied educators in knots and emptied some school library shelves.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What do Florida's laws say?

One law requires every book in a school's possession to be posted on an online database and vetted by "media specialists" to ensure it's "free of pornography." State guidance urges schools to "err on the side of caution" on what they approve. In two large school districts, which contain the cities of Bradenton and Jacksonville, administrators ordered the removal or concealment of tens of thousands of books in their schools; students returned from their winter break to find bookshelves empty or covered with paper. Florida's "Parental Rights in Education" law bans discussions of sexual orientation or gender identity from kindergarten to third grade, while its "Stop WOKE Act" outlaws books that could lead any student to feel race or sex-related "guilt, anguish or other forms of psychological distress."

How have teachers responded?

Many Florida teachers are "scared to death" to tell students anything about America's racial history, said Charles White, executive director of the Social Science Education Consortium. To pass muster, one textbook publisher even eliminated any mention of race in telling the story of Rosa Parks refusing to change her seat on a public bus. DeSantis insists it's "a nasty hoax" that state laws require broad book bans, and that he is simply fighting "woke" leftists who are "trying to pollute and sexualize our children."

What is the impact of these laws?

They've made teachers paranoid and deeply fearful about losing their licenses and being charged with crimes. In some states, "tip lines" now exist for reporting teachers who discuss "inappropriate" topics. Arizona now requires parental approval before teachers can include books containing any references to sex. Some educators, such as Stuart, Florida, middle school science teacher Arian Dineen, say the rules are forcing teachers to consider leaving the profession. "It feels like you can be reported by anyone at any time," she said. "It feels very much like '1984' or the McCarthy era."

Do most parents support this?

No. A Fox News poll released in April revealed that 77% of parents were "extremely" or "very" worried about book bans. Other polls found that about 80% of both Republicans and Democrats say books should never be banned for discussing race, slavery or critical views of U.S. history. Democratic pollster Guy Molyneux said a majority of parents say they are "uncomfortable with some of this [gender] transitional treatment kids are getting, and 'I don't know how I feel about pronouns, but I do not want them banning books.'"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Going after publishers

Starting July 1, publishers who sell or distribute books with "sexually explicit" material to Tennessee schools face felony charges and fines of up to $100,000 per violation. Lawmakers in Texas and Oklahoma are considering new age-based restrictions on publishers who want access to their public schools. Some companies already are letting state laws influence editorial decisions. Maggie Tokuda-Hall's grade-school picture book "Love in the Library," first published by a small press last year, recounts how her grandparents met in a Japanese internment camp during World War II. When children's book giant Scholastic offered to license it, it asked her to remove references to anti-Japanese racism from her author's note, arguing that teachers might be dissuaded from using the book in this "politically sensitive" moment. The author flatly refused. "I'm typically a very compromising person," she said. "But when you omit the word 'racism' from a story about the mass incarceration of a single group of people based on their race, there's no compromise to be had."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

The current state of American sanctuary cities

The current state of American sanctuary citiesSpeed Read Sanctuary cities are buckling under the pressure of the influx of asylum-seekers

-

How much money each presidential candidate has raised

How much money each presidential candidate has raisedThe Explainer The donation emails and fundraising events are in full swing

-

The hidden architect of the Supreme Court

The hidden architect of the Supreme CourtSpeed Read All six conservative Supreme Court justices were seated with major help from Leonard Leo of the Federalist Society

-

Will Russia have to revive the Ukraine grain deal?

Will Russia have to revive the Ukraine grain deal?Speed Read Blocking the shipment of Ukrainian agricultural products could put millions of people around the world in danger of severe hunger

-

What is 'Bidenomics' and why is it suddenly everywhere?

What is 'Bidenomics' and why is it suddenly everywhere?Speed Read As the president works to tout his economic agenda, he's increasingly embraced the term

-

DeSantis' pledge to end birthright citizenship marks a new era for Republicans

DeSantis' pledge to end birthright citizenship marks a new era for RepublicansSpeed Read He's not the first to demand a challenge to the 14th Amendment — and won't be the last

-

4 global organizations the US rejoined after Trump pulled the plug

4 global organizations the US rejoined after Trump pulled the plugSpeed Read Biden has made headway in reversing the former president's decision to withdraw from multiple global organizations

-

Why Republicans are trying to make Trump's trial about Hillary Clinton

Why Republicans are trying to make Trump's trial about Hillary ClintonSpeed Read The upsides and pitfalls of Hillary emails whataboutism