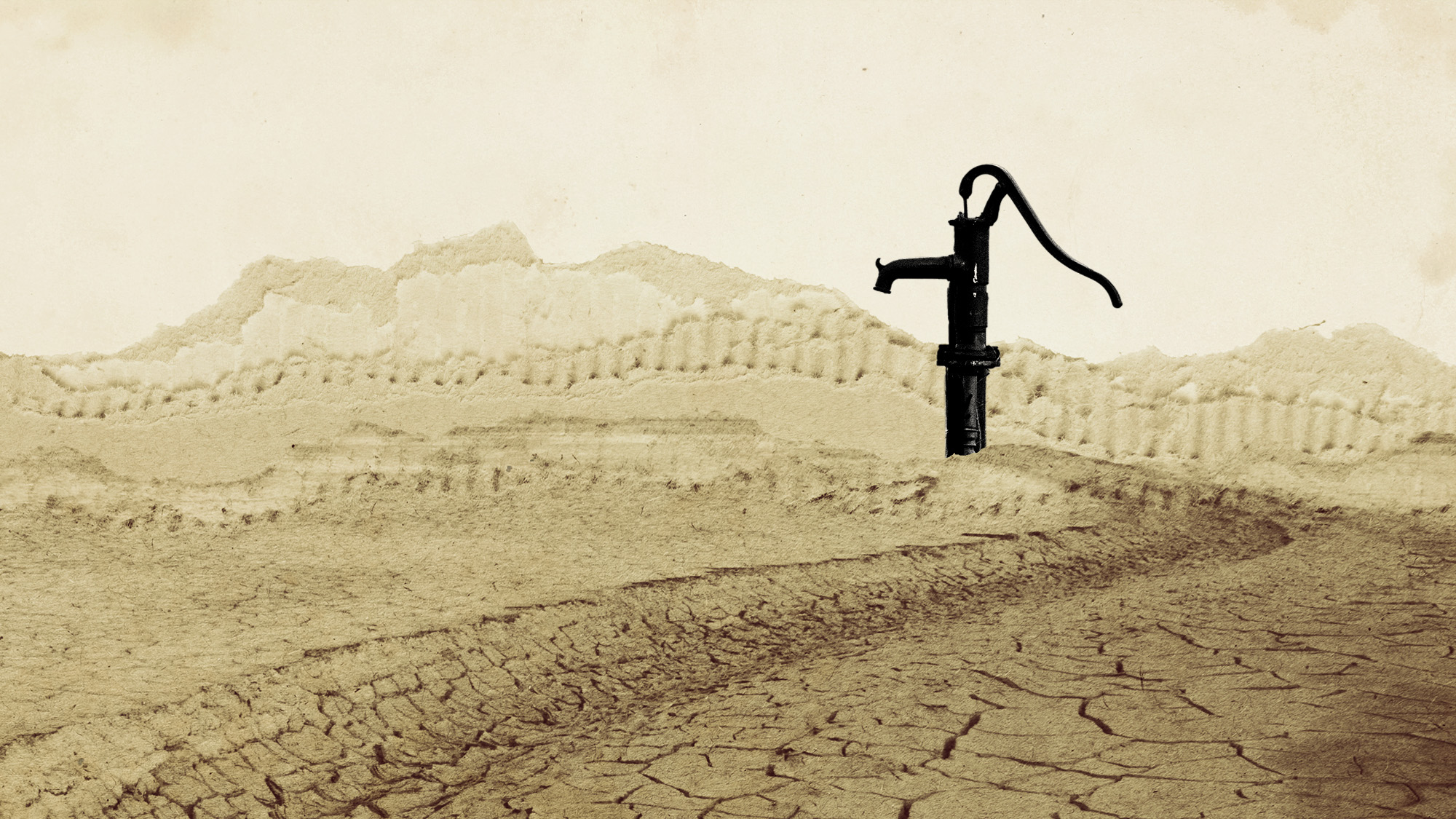

The US is facing a groundwater crisis

Stress is high as water runs low

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Water is one thing people cannot live without. Yet the United States' access to water is slowly becoming scarcer. The country contains many underground aquifers that hydrate and irrigate most of the 48 contiguous states. The problem is that Americans are taking more water than can be replenished, which could lead to catastrophic consequences in the future. Climate change is already making rain and snowfall unreliable, and as temperatures continue to rise, water will only become scarcer.

Running dry

Much of the U.S.'s development over the last few centuries was thanks to the country's bountiful supply of groundwater aquifers. Unlike rivers and lakes, aquifers hold freshwater underground, and that freshwater is then pumped out of the aquifers for irrigation and drinking. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), surface water can be "scarce or inaccessible," while "groundwater supplies many of the hydrologic needs of people everywhere," acting as a "source of drinking water for about half the total population and nearly all of the rural population," and "providing over 50 billion gallons per day for agricultural needs."

Despite groundwater being an integral part of American life, access to groundwater is on borrowed time. "Huge industrial farms and sprawling cities are draining aquifers that could take centuries or millenniums to replenish themselves if they recover at all," according to an analysis by The New York Times. Many regions of the country are experiencing groundwater depletion because the aquifers are being pumped faster than they can be replenished. Approximately 45% of the water wells examined in the Times analysis "showed a statistically significant decline in water levels since 1980," with 40% reaching "record-low water levels during the past decade." Warigia Bowman, a law professor and water expert at the University of Tulsa, called the depletion a "crisis" to the Times, adding that "there will be parts of the U.S. that run out of drinking water."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Groundwater depletion can lead to a number of environmental consequences. Water wells can dry up over time; the level of water in streams and lakes can be reduced; land subsidence, which is when the soil collapses, compacts and drops because water is removed, can become more common; and water quality can deteriorate, according to the USGS. There could also be several social repercussions including, "lower property values, higher water bills, limits on development, failing farms and giant sinkholes opening up in the ground we live on," John Sabo, director of the ByWater Institute at Tulane University, wrote for Forbes.

Scarce regulation

Groundwater aquifers suffer from a lack of regulation. "The federal government plays almost no role, and individual states have implemented a dizzying array of often weak rules," the Times analysis detailed. "The problem is also relatively unexamined at the national scale. Hydrologists and other researchers typically focus on single aquifers or regional changes." The issue has become a "tragedy of the commons" which "refers to a situation in which individuals with access to a public resource (also called a common) act in their own interest and, in doing so, ultimately deplete the resource," as defined by Harvard Business School.

Minimal regulation coupled with the ongoing climate crisis is deepening the issue. "Rising temperatures often means reduced snowpack, which in turn means less water flowing through rivers — pushing farmers and cities to lean more heavily on groundwater. But those same rising temperatures also mean plants and lawns require more water," the Times explained. The country's water bodies are already feeling the strain. The Colorado River, for example, has been rapidly depleting, and government intervention has been required to divide water rights among the states reliant on the river, including California, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Wyoming. "Water scarcity and water quality issues will reach crisis levels in localities all over America in the next several decades," predicted Steve Cohen in an essay for State of the Planet by Columbia University's Climate School.

The good news is there are actions that can lessen the strain on aquifers. Rainfall and snowpack are crucial to replenishing aquifers, but the country has historically struggled with managing collection. "It is crucial to shift our mindset about groundwater and see aquifers as infrastructure to be managed in ways that capture rain during extreme events," Sabo wrote in Forbes. Evaluating the U.S. agricultural system, which has been the largest user of groundwater in the country, can play a crucial role as well. Specifically making an effort to plant less water-reliant crops or focusing on dryland farming, which uses rainwater rather than irrigation, can reduce U.S. agriculture's reliance on groundwater. "The future of America's water supply is an open question," Cohen remarked. "The need for an adequate water supply is not open to question."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Why broken water companies are failing England and Wales

Why broken water companies are failing England and WalesThe Explainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives