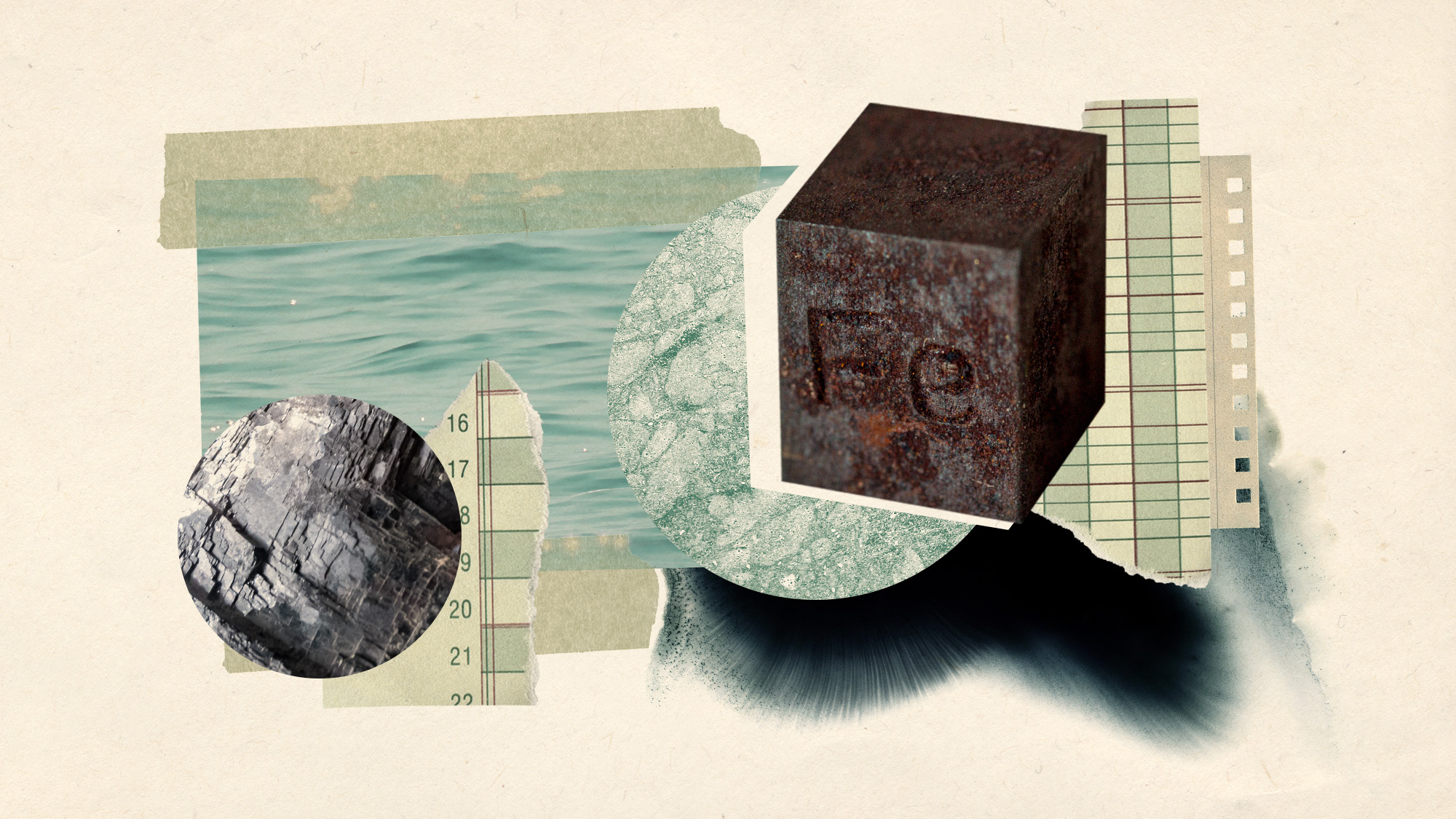

Iron fertilization: Scientists want to add the element to the ocean to capture carbon

Adding metal to marine life

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The climate is warming, and much of the increase is due to greenhouse gases, the most prevalent gas being carbon dioxide. Methods for removing existing carbon from the atmosphere are in the works, and some experts are arguing in favor of iron fertilization, a geoengineering approach which would help oceans trap atmospheric carbon. While the method has potential, the consequences of implementing it are still largely unknown.

Iron in the ocean

An article published in the journal Frontiers in Climate lays out a program for implementing iron fertilization to help fight climate change. Ocean iron fertilization (OIF) is a "technique where small amounts of micronutrient iron are released onto the surface of the sea to stimulate the growth of marine plants known as phytoplankton," said Euronews. "This rapid growth removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. When the plankton die or are eaten, some of that carbon is captured as it sinks deep into the ocean." Geoengineering like OIF has long been in discussion as a way to mitigate carbon emissions.

"Given the ocean's large capacity for carbon storage … enhancing the ocean's natural ability to store carbon should be considered," Paul Morris, one of the authors of the study and the project manager for international experts group Exploring Ocean Iron Solutions (ExOIS), said in a statement. ExOIS wants to conduct iron fertilization trials to determine whether the technology could be implemented on a larger scale. "This is the first time in over a decade that the marine scientific community has come together to endorse a specific research plan for ocean iron," Ken Buesseler, the study's lead author and executive director of the ExOIS project, said in the statement. The program wants to raise $160 million for the trial and has already received a $2 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Oceanic objections

Not everyone is on board with investing in iron fertilization. Many worry that "fertilization could create 'dead zones' where rampant algal blooms would consume all the oxygen in the water, snuffing out other life," said Scientific American. "Phytoplankton blooms could also consume nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen that then wouldn't be available for organisms elsewhere, a phenomenon known as 'nutrient robbing.'" There is little known about how iron fertilization will interact with other climate factors that affect marine life, like warming oceans.

In addition, iron fertilization may not be as effective at removing carbon as some experts claim. "Even at its peak performance, the technique just can't store that much carbon," Alessandro Tagliabue, an ocean biogeochemist at the University of Liverpool, said to Hakai Magazine. "Setting up a large-scale nutrient fertilization project would require mining the minerals and building infrastructure to get them into the ocean. These activities would emit carbon, lowering the overall carbon sequestration potential by the time the nutrients hit the water."

However, some sacrifices could be necessary to ensure progress. "It's a small change in biology, relative to doing nothing and watching this planet boil," Buesseler said to Scientific American.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives