The Crown vs. Greenpeace: who owns the seabed?

Environmental group is threatening to sue the Crown Estate over its ‘aggressive’ use of its monopoly position

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Greenpeace is threatening to sue the Crown Estate, accusing it of exploiting its monopoly ownership of the nation’s seabed. The environmental group says that King Charles’ property management company has become “aggressive” in how it auctions seabed rights, and that this is hitting energy bill payers in the pocket.

Which seabeds do the Crown Estate own?

In 1951, the foreign secretary, Herbert Morrison, concluded that the waters around Britain and the land beneath them did not belong to anybody. But in 1959, the same year large quantities of gas were discovered beneath Dutch waters, the Crown Estate’s legal adviser “proposed enshrining in law the extension of Crown lands to the whole of the continental shelf”, said Prospect.

The 1964 Continental Shelf Act duly gave the Crown Estate rights to the seabed and subsoil, allowing for activities like oil and gas extraction in a range that, at its largest, extends to 200 nautical miles from the coast. The seabed is also leased out for offshore wind farms, cables, pipelines and aquaculture.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Since then, the monarchy has “gradually plundered” the seabed, “transforming it into nothing less than a rentier capitalist empire”. From 2013–23, that empire is thought to have earned the royal family around £193 million.

What does that mean for the offshore wind sector?

Greenpeace says the Crown Estate has “exploited its monopoly position to charge hefty fees” for leases of the seabed, leading to a pricing system that’s “massively boosted the estate’s profits” and driven up costs for the wind power sector and, in turn, energy bill payers.

But a Crown Estate spokesperson told The Guardian that the environmental group has “misunderstood the Crown Estate’s legal duties and leasing processes”. Taxpayers, they said, “benefit” from the estate’s stewardship and development of “our scarce and precious seabed resource”.

What about other countries?

Countries across the world are “using the politics of nationalism to permanently stamp their mark on the topography of the ocean”, said The Guardian last year. Some are “seeking to demonstrate that a nearby seabed is part of their continental shelf and therefore belongs to them”, which allows them to “potentially extend its underwater sovereignty by as much as 350 nautical miles from its coastline”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To make such a claim, they have to name the area they are claiming and they do this by petitioning the International Hydrographic Organization, an intergovernmental body with 102 member states.

An examination of this naming process shows the surge in interest in the seabed. Canadian geographer Sergei Basik, who coined the term bathyonyms to describe natural features on the ocean floor, has found that during the 20th century just 17 names for bathyonyms were proposed on average each year. Since 2016, more than 1,000 names have been submitted, with Japan leading the way on 615, followed by the US (560), France (346), Russia (313), New Zealand (308) and China (261).

Chas Newkey-Burden has been part of The Week Digital team for more than a decade and a journalist for 25 years, starting out on the irreverent football weekly 90 Minutes, before moving to lifestyle magazines Loaded and Attitude. He was a columnist for The Big Issue and landed a world exclusive with David Beckham that became the weekly magazine’s bestselling issue. He now writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Metro, FourFourTwo and the i new site. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

Pros and cons of geothermal energy

Pros and cons of geothermal energyPros and Cons Renewable source is environmentally friendly but it is location-specific

-

Megabatteries are powering up clean energy

Megabatteries are powering up clean energyUnder the radar They can store and release excess energy

-

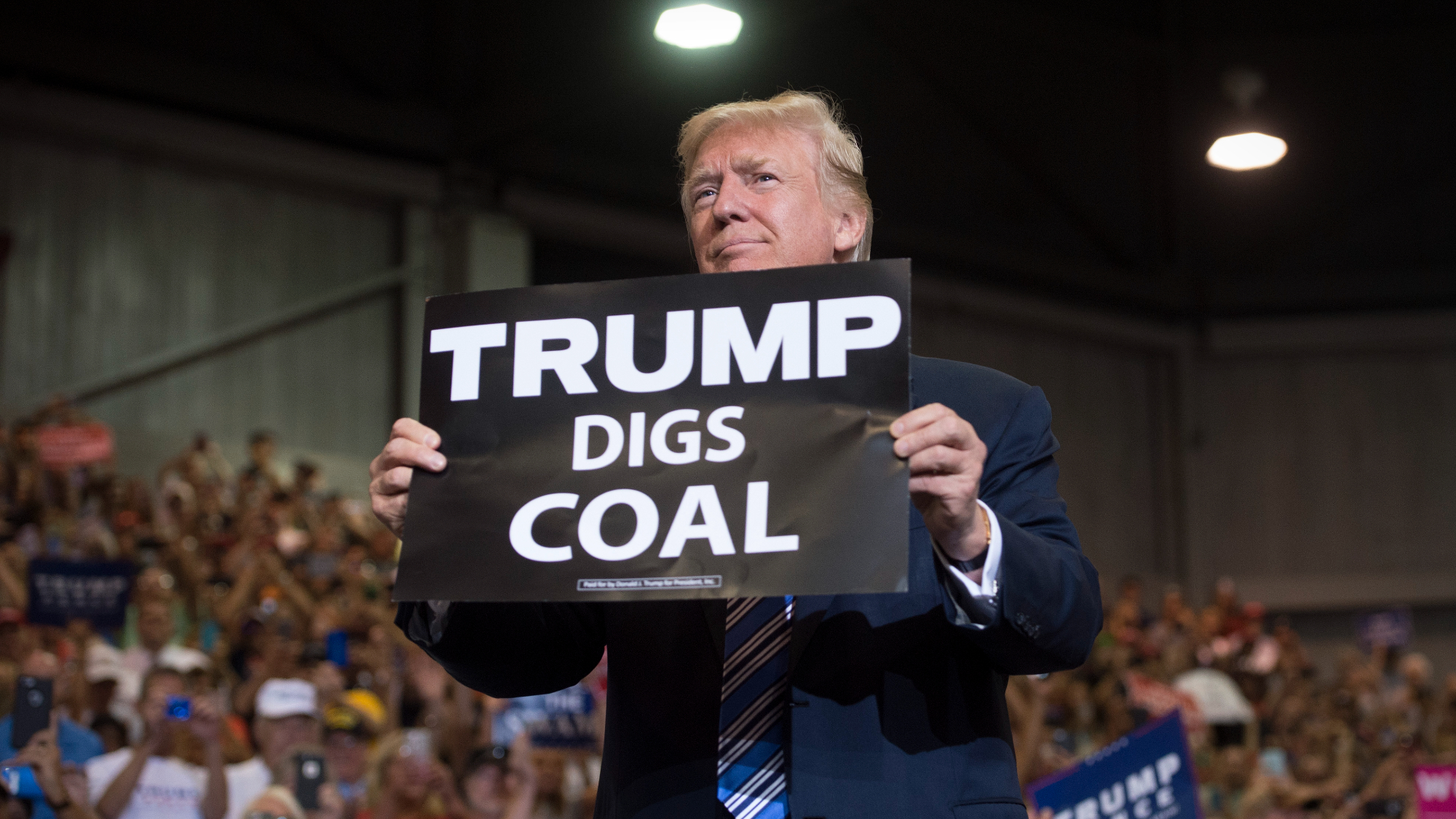

Renewables top coal as Trump seeks reversal

Renewables top coal as Trump seeks reversalSpeed Read For the first time, renewable energy sources generated more power than coal, said a new report

-

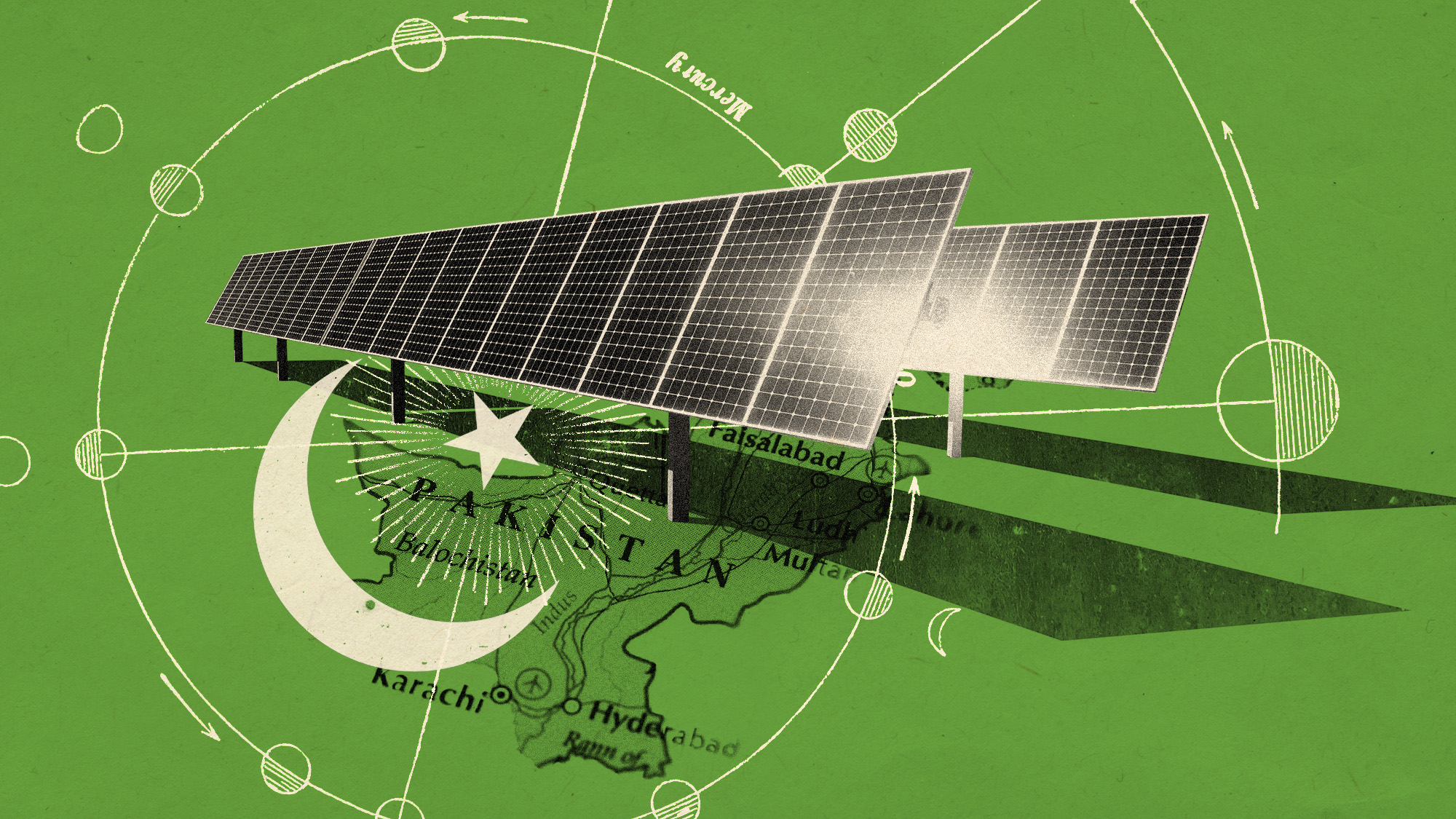

Pakistan's solar panel boom

Pakistan's solar panel boomUnder The Radar A 'perfect storm' has created a solar 'revolution' in the south Asian country

-

Greenpeace, Energy Transfer and the demise of environmental activism

Greenpeace, Energy Transfer and the demise of environmental activismThe Explainer Court order forcing Greenpeace to pay $660m over pipeline protests will have 'chilling' impact on free speech, campaigners warn

-

Airlines ramp up the hunt for sustainable aviation fuel

Airlines ramp up the hunt for sustainable aviation fuelUnder The Radar Several large airlines have announced sustainability goals for the coming decades

-

What are Trump's plans for the climate?

What are Trump's plans for the climate?Today's big question Trump's America may be a lot less green

-

The Australia-Asia Power Link

The Australia-Asia Power LinkUnder The Radar New electricity infrastructure will see solar power exported from Down Under to Singapore