Why men have a bigger carbon footprint than women

'Male identity' behaviours behind 'gender gap' in emissions, say scientists

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Men generally have bigger feet than women – and a bigger carbon footprint too, according to new research.

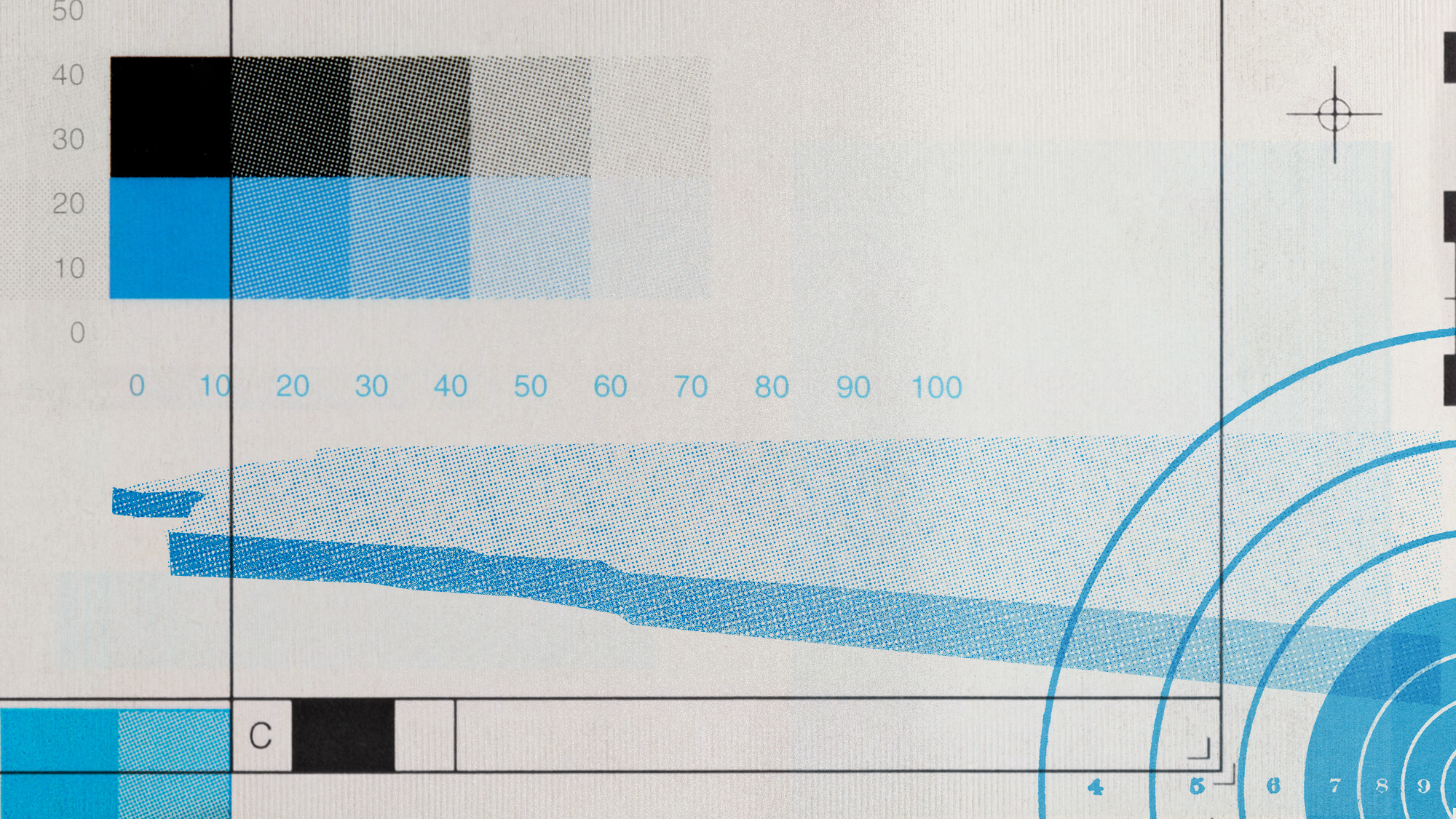

A joint UK-French study, at the LSE's Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, found that men cause 26% more planet-warming gas emissions than women do, mainly because of the cars they drive and the meat they eat.

The researchers analysed French survey data on food consumption and transport patterns – the two factors that, together, account for 50% of the carbon footprint of French households. They found that, for men, the average annual carbon footprint associated with food and transport was 5.3 tonnes of carbon-dioxide equivalent; for women, it was 3.9.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The difference between the sexes is mainly accounted for by men's higher consumption of red meat and greater use of cars – both "often associated with male identity", concluded the study authors in an LSE press release. "Our results suggest that traditional gender norms, particularly those linking masculinity with red-meat consumption and car use, play a significant role in shaping individual carbon footprints," said study co-author Ondine Berland, a LSE fellow in environmental economics.

'Striking' gender gap

"Research into gender gaps is often plagued by difficult decisions about which factors to control for," said The Guardian. Men need more calories than women, for example, but "they also eat disproportionately more than women". Men also tend to drive longer distances when commuting, and they also generally have higher incomes, which are themselves "correlated with higher emissions".

But, even after the study authors controlled for socioeconomic factors such as income, job type, household size and education, the emissions gap between men and women was still a significant 18%.

It is "quite striking that the difference in carbon footprint in food and transport use" between French men and women is "around the same as we estimate" globally for high-income people compared to lower-income people, study co-author Marion Leroutier, an assistant professor at Crest-Ensae Paris, told the paper.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Higher personal costs

The carbon-footprint gap the study identifies could help explain "the growing climate concern gap between men and women", said The Independent. It's possible that men are less inclined to support climate action because there are "higher personal costs" for them in doing so, such as giving up red meat and reducing car use.

Alternatively, it could be that women's lower-carbon lifestyles "might reflect and reinforce deeper values and priorities": their carbon footprints are smaller because they're more concerned about the climate.

Either way, it's clear that "public messaging and policy design" on lowering emissions needs "to take social norms and gender roles into account, not just market signals or price incentives". Strategists wanting to target "high-emission activities like driving and eating meat" need to factor in that this will "disproportionately affect men, especially those who associate consumption with identity or status".

And the rewards of successful messaging could be impressive. If all adult men adopted the average food and transport "carbon intensity of women", say the study authors, France's emissions from food and transport would fall by more than 13 million tonnes of carbon-dioxide equivalent a year. That's about triple the emissions decrease that France is targeting across those sectors, to comply with its 2030 climate targets.

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures