European elections: how the vote works

If ballot papers for this election seem longer than usual, that’s because they are

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Despite plans to go ahead with Brexit, the UK will now participate in elections to the European Parliament tomorrow.

Voting in this election will take place across Europe between 23 May and 26 May, with different countries holding votes on different days. The majority of member states vote on Sunday 26 May.

Here is what you need to know about voting in the UK.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Voting in a region rather than a constituency

The way the country is carved up into voting areas is different to a general election. Rather than hundreds of constituencies, the UK is divided into 12 parts. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are represented as whole nations while England is divided up into nine regions.

Different regions and nations get different numbers of seats. In England, for example, the North-West gets eight and the South-East gets ten. Scotland gets six. Wales gets four. Northern Ireland gets three.

What’s on the ballot paper

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

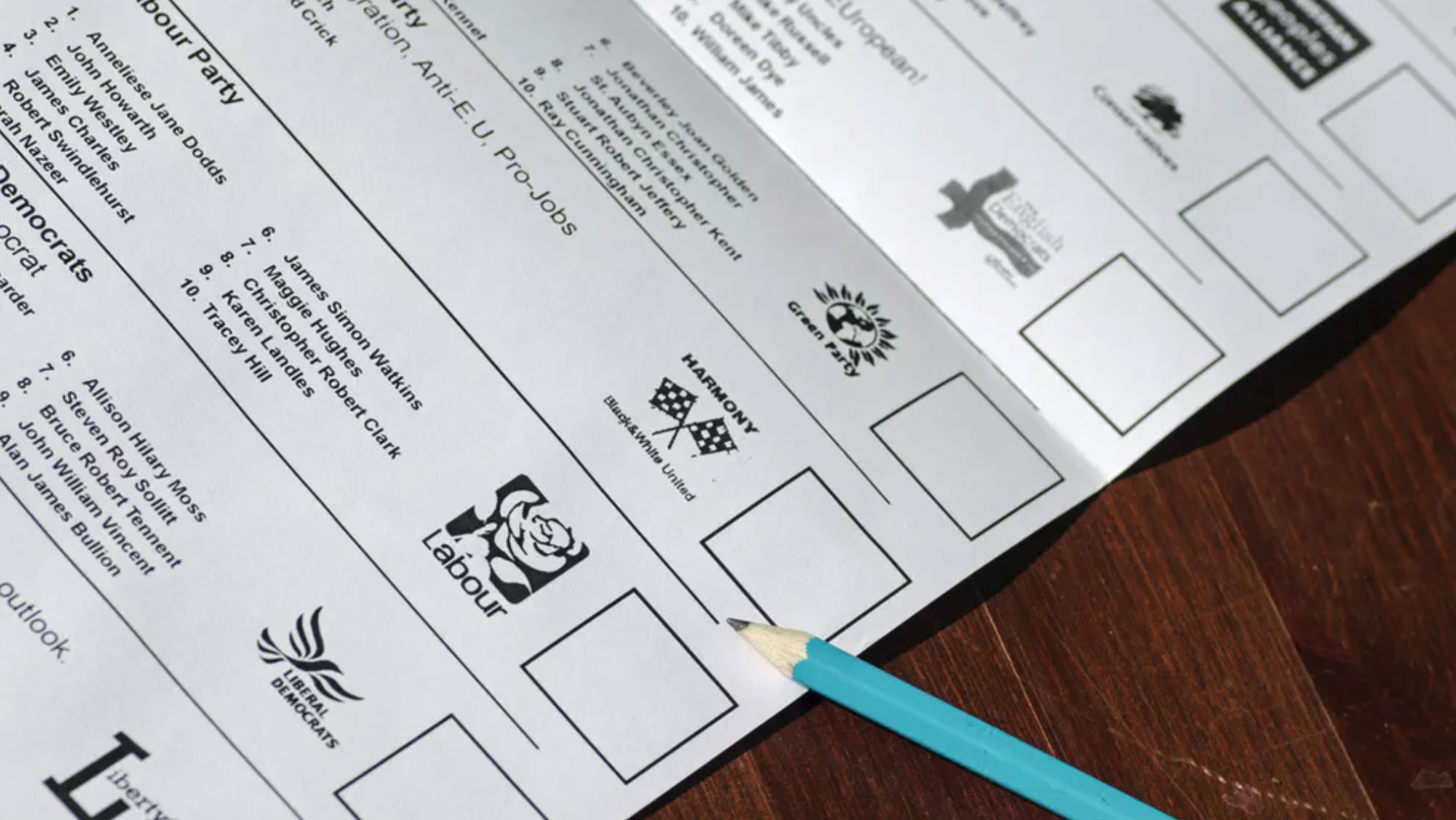

Since 1999, MEPs from the UK have been chosen using a closed list system (except in Northern Ireland). That means the ballot paper will show a list of parties in boxes. Within each party box there will be a list of candidates.

In a region which gets three MEPs, parties will usually list three candidates, if ten, ten candidates. They can’t list more but would be allowed to list fewer. Independent candidates are also listed on the ballot paper separately.

But voters don’t pick and choose between individual MEP candidates. They get one vote and use it to choose one party, or one independent, marking the box with an X.

How the counting works

The way votes are counted in a European election is different to a general election, too. A system called d’Hondt is used, which is meant to produce a broadly proportional allocation of seats.

The total number of votes for each party in each region are counted and then put in order. The party at the top gets seat number one. That is allocated to the candidate at the top of its list.

The winning party’s vote total is then halved and the whole list is looked at again. Whichever party is on top of this reordered list gets the next seat. That may well be the same party that won the first seat, if it has secured enough support, or it may be another party.

The party at the top of the second list (if it is a different party) then gets its vote total divided in half and the process is repeated. (If the same party has just won twice, the division is by three). This goes on until all the seats in the region are filled. Parties with less support may never reach the top and won’t win a seat. Chances vary depending on the size of the region.

In Northern Ireland, the election is carried out by single transferable vote, a system in which voters do have more than one choice. Citizens are used to this as it is the method for local elections and the Northern Ireland Assembly. They show their preferences by voting 1,2,3 and so on. In an STV system there is no real chance of a “wasted vote”.

Moving down the list

So, why is there a list of candidates if you only get to vote for a party? It’s because when each party chooses its representatives, it puts them in priority order. The candidate at the top of the list is the one the party most wants to get elected.

Candidates on the lower rungs of the ladder have no realistic chance of being elected – I say this as someone who has previously been number nine of ten.

But if an MEP resigns or dies during their term in parliament, their place is filled by the next person down the list (rather than in a by-election). This has actually happened. When Diana Wallis, Liberal Democrat MEP for Yorkshire and the Humber resigned in 2012, she was replaced by Rebecca Taylor. For these purposes, defecting out of a party does not count as a vacancy.

How Brexit changes the game

Voters may feel the ballot papers for this election are longer than usual. That’s because they are. They feature several new parties, such as Change UK and the Brexit Party, as well as some other less familiar ones, such as The Yorkshire Party.

We are also seeing the rise of so-called “celebrity candidates” such as Boris Johnson’s sister Rachel Johnson for Change UK and former Conservative minister Ann Widdecombe for the Brexit Party. But it’s worth remembering that these celebrity candidates are there to raise profile more than anything. Because the contest is between parties, no aspiring MEP can really call on a “personal vote”.

Of course the UK MEPs may not take their seats, or may take them only for a short period of time. Assuming the UK leaves the EU, some other countries are electing “shadow MEPs” who will effectively take up the empty seats in the parliament on the UK’s departure.

European elections in the UK are rarely about Europe. They are generally seen, by journalists, campaigners and public alike, as massive opinion polls. In fact I have seen some campaign leaflets in the past which fail to mention the parliament at all.

This time however, the elections are about Europe, although they are generally about decisions MEPs have no power to take. So a vote for the Brexit party, for example, won’t give its MEPs the power to speed up Brexit (the European Parliament can’t do this). However people vote though, will act as a signal to the UK government and House of Commons about what they think of the current state of play with Brexit.

Paula Keaveney, Senior Lecturer in Politics, Edge Hill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxes

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxesThe Explainer Your status will determine how much you pay, plus the tax credits and deductions you can claim

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?Today's Big Question Europe's two biggest economies sign first treaty since WWII, underscoring 'triangle alliance' with France amid growing Russian threat and US distance

-

Is the G7 still relevant?

Is the G7 still relevant?Talking Point Donald Trump's early departure cast a shadow over this week's meeting of the world's major democracies

-

Angela Rayner: Labour's next leader?

Angela Rayner: Labour's next leader?Today's Big Question A leaked memo has sparked speculation that the deputy PM is positioning herself as the left-of-centre alternative to Keir Starmer

-

Is Starmer's plan to send migrants overseas Rwanda 2.0?

Is Starmer's plan to send migrants overseas Rwanda 2.0?Today's Big Question Failed asylum seekers could be removed to Balkan nations under new government plans

-

Has Starmer put Britain back on the world stage?

Has Starmer put Britain back on the world stage?Talking Point UK takes leading role in Europe on Ukraine and Starmer praised as credible 'bridge' with the US under Trump