Is another Cultural Revolution underway in China?

Big changes in China have some worried a new version of Chairman Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution is underway. Here's everything you need to know.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

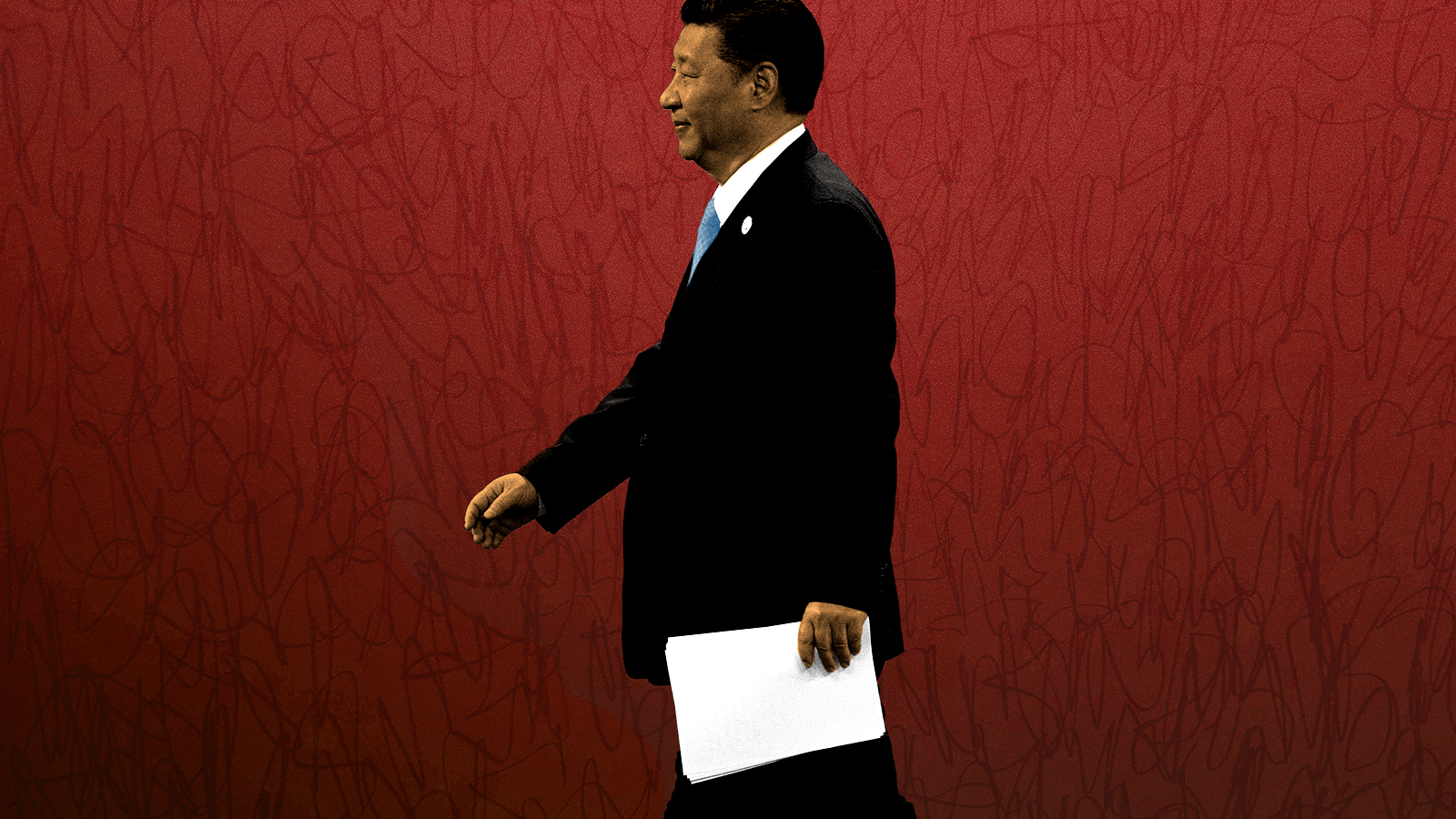

Chinese President Xi Jinping is cracking down on several sectors of Chinese society, including technology and entertainment. This has some Beijing watchers worried a new version of Chairman Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution is underway. Here's everything you need to know.

What was the Cultural Revolution?

It was a brutal 10-year period between 1966-76 (with most of the violence occurring in the first five years) that led to hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of civilian and military deaths in China. The era began when Chairman Mao Zedong, whose pre-eminent position in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had weakened, launched his plan to "purge all potential opposition to his leadership" before mobilizing the masses throughout the country to further strengthen his grasp on power. He legitimized a student protest movement called the Red Guard, which morphed into a revolutionary paramilitary group and set out on a "class cleansing" campaign, first in urban areas and eventually the countryside. Their targets were vaguely-defined "rightist" and "reactionary" threats, including Red Guard members' own educational system, and the movement ultimately led to "indiscriminate destruction of all things and people deemed non-Leftist." Anything having to do with religion and the West was considered fair game, so in addition to the human atrocities, artifacts, historical records, and foreign embassies were destroyed.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why do people see similarities between then and now?

While never particularly tolerant of dissent or other forms of behavior that appear out of step with the regime, the CCP's latest efforts have recently become harsher in severity and wider in scope. Many people across the entertainment industry have faced backlash from Beijing. Some have been cited for specific infractions, including actress Zheng Shuang, who has been accused of tax evasion. Other cases are more mysterious. For example, Zhao Wei, a famous billionaire actress, has been inexplicably scrubbed from the internet. The party has also capped the amount of time children can spend playing video games per week, and has looked to stifle celebrity fan culture.

Does the crackdown go beyond the entertainment world?

Yes, in fact, it's probably more accurate to say that the attacks on the entertainment industry are spillover from Xi's larger plan to rein in capitalism and have the party play a much more active role in the Chinese economy. While Xi isn't attempting to completely eradicate market forces, he is aiming to make life a lot tougher for wealthy entrepreneurs and large companies, perhaps exemplified by a slew of regulations against the tech industry and the possibility that Beijing will allow the cash-starved major property developer Evergrande collapse. Xi has painted this movement in ideological terms with an eye toward restoring Mao's socialist vision after years of evolution toward Western-style capitalism.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Has the effort reached the classroom?

Recently, the government introduced a new ideology into the nationwide curriculum. It's called "Xi Jinping thought," and is geared toward helping teenagers "establish Marxist beliefs" through the specific views of the president. China's Ministry of Education said it wants to "cultivate the builders and successors of socialism with an all-around moral, intellectual, physical, and aesthetic grounding." "Xi Jinping thought" isn't a brand new phenomenon — it was enshrined in the constitution in 2018 and has already been introduced in some universities and youth political circles, but now it will become much more widespread. The lessons, which will be integrated from primary school up to university, include education on national security, as well as labor education to develop the younger generation's "hard-working spirit."

So, is a second Cultural Revolution coming?

Analysts can't agree. Some are ringing the alarm bells, while others are wary of jumping to conclusions. There seems to be little doubt that Xi is looking to reshape China's business and cultural practices, but there are marked differences between the current situation and that of the past. Xi is launching a top-down effort at a time when he faces no internal threats to power — his rule is stable. That wasn't the case with Mao, who despite his authoritarian legacy, didn't actually have as firm a grasp on executive power in the lead up to the Cultural Revolution as Xi does now. Today, it's the government going on the offensive, and there's no need for Xi to rally student paramilitaries to bolster his position. It's also important to note that while Xi is echoing some of Mao's rhetoric, he is no fan of the Cultural Revolution. His father, a veteran of the Communist revolution, was persecuted during that time, and Xi has publicly criticized the era in the past for bringing the Chinese economy "to the brink of collapse."

What's it really about then?

It's all likely part of Xi's efforts to stay in power in the long run and maintain relevance for himself and the CCP. "Xi's motivation and Mao's are … different," Kerry Brown, a professor of Chinese Politics and King's College London, writes for The Conversation. Mao was intent on transforming a "moribund" country "enslaved by tradition" into his version of a modern society. For Xi, the goal is more simple: make sure the party doesn't lose the battle for attention to other aspects of society. So, in other words, Xi isn't looking to wipe 21st-century China clean. Instead, he's looking to limit distractions — video games, celebrity culture, etc. — and make sure the party retains a prominent place in people's minds. This allows him to pick his spots as he taps into some resentment toward wealth within the country without actually fomenting widespread popular rebellion, Ming Xia, a political science professor at City University of New York, told The Financial Times. "He has never been a revolutionary like Mao," Ming said.

Tim is a staff writer at The Week and has contributed to Bedford and Bowery and The New York Transatlantic. He is a graduate of Occidental College and NYU's journalism school. Tim enjoys writing about baseball, Europe, and extinct megafauna. He lives in New York City.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

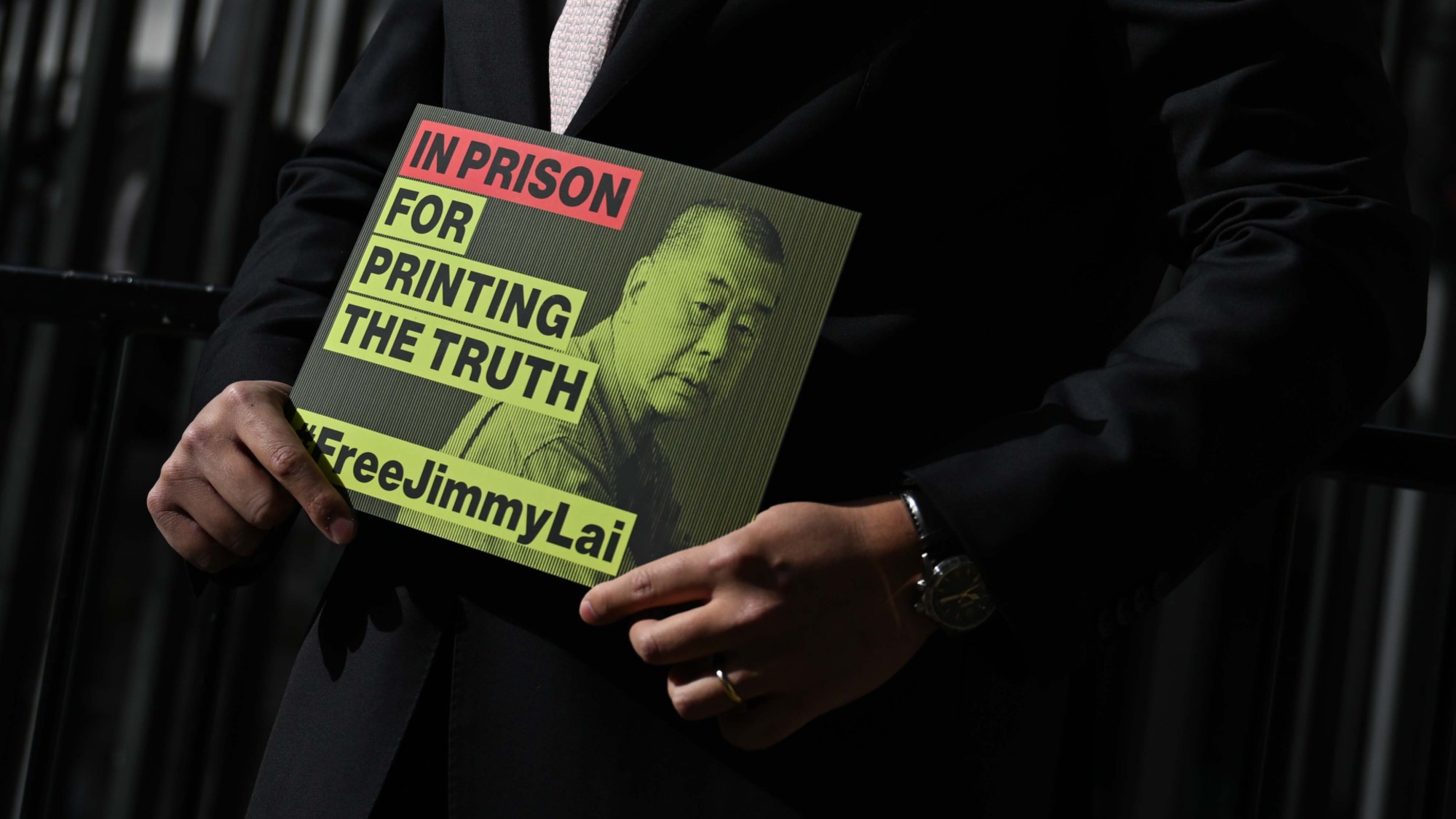

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What do Xi’s military purges mean for Taiwan?

What do Xi’s military purges mean for Taiwan?Today’s Big Question Analysts say China’s leader is still focused on reunification

-

What is at stake for Starmer in China?

What is at stake for Starmer in China?Today’s Big Question The British PM will have to ‘play it tough’ to achieve ‘substantive’ outcomes, while China looks to draw Britain away from US influence

-

‘It’s good for the animals, their humans — and the veterinarians themselves’

‘It’s good for the animals, their humans — and the veterinarians themselves’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

What is China doing in Latin America?

What is China doing in Latin America?Today’s Big Question Beijing offers itself as an alternative to US dominance

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story