French election 2017: How does the voting system work?

As France prepares to choose its next president, The Week reviews the merits of its two-round voting system

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

France goes to the polls for the second time on Sunday, when voters will choose either far-right candidate Marine Le Pen or centrist Emmanuel Macron to be the country's next president.

Whoever wins, it is guaranteed to be a historic day - the first time that neither of the two main political parties, the Socialists or the Republicans, appears on the final ballot paper.

Their candidates, usually the frontrunners, fell at the first hurdle and failed to secure enough votes to make it through the first round of elections on 23 April.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Ahead of the final vote, we take a look at the mechanics of the French election system and consider whether a two-round vote could work in the UK.

What is the French system?

France has a hybrid system comprising a president and a parliament, made up of the National Assembly and the Senate. The National Assembly and the president are elected by public votes.

How does the French voting system for the president work?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Elections are held every five years, using a two-round voting system to determine its president - the nation's head of state, commander of the military and chair of government.

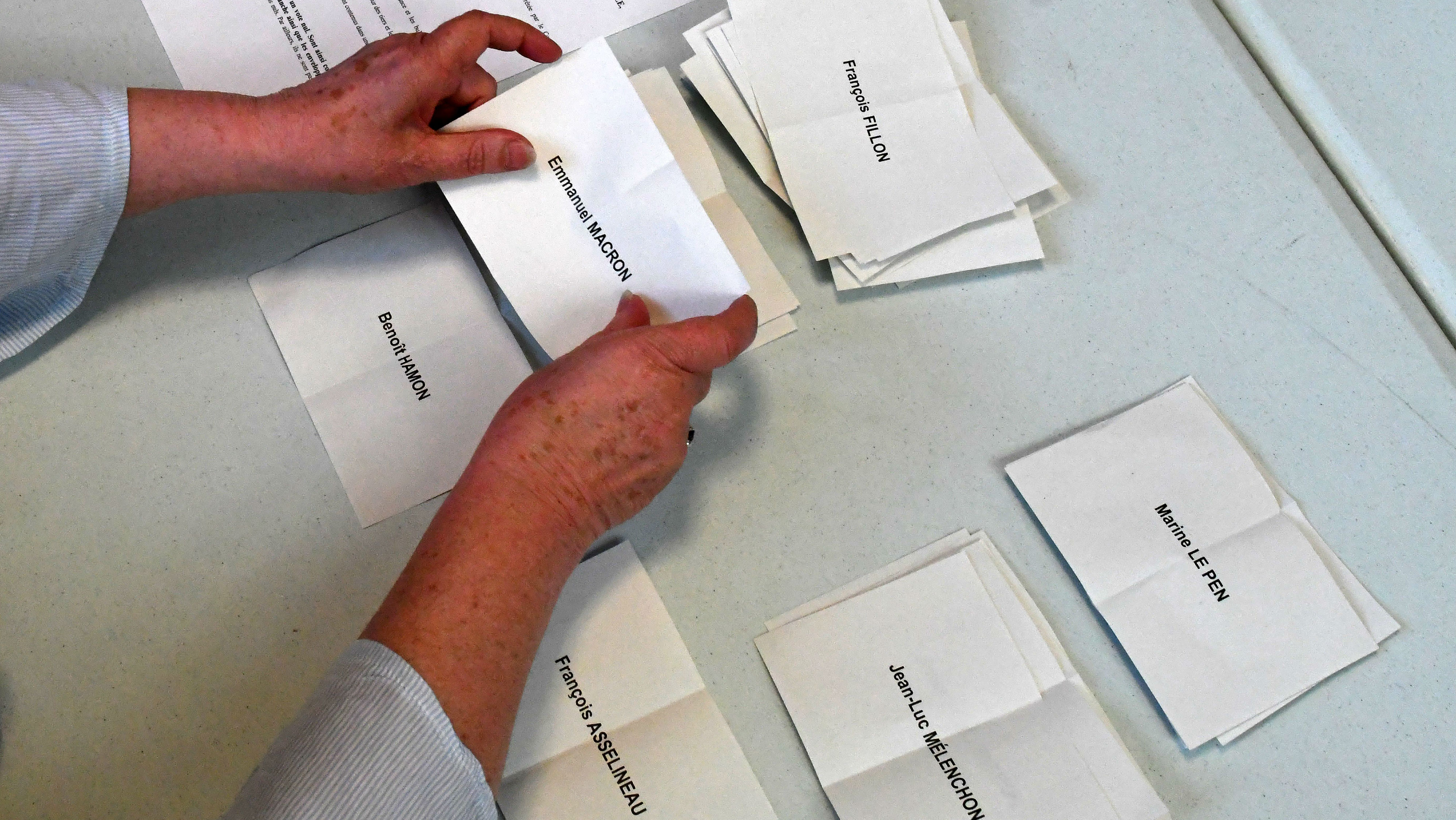

In the first round of voting, all candidates, who must have the backing of at least 500 elected officials, stand. Then the two candidates with the highest number of votes go head-to-head in a second poll two weeks later.

In theory, a winner can be declared after round one if one candidate secures an outright majority. However, this is yet to happen.

What about the National Assembly vote?

Almost as soon as the presidential race is over, France prepares for the election of the National Assembly, during which it appoints 577 deputies, similar to the UK's members of parliament, in a further two-round process.

Usually voters tend to vote for a president and assembly majority from the same party or side.

Problems rise, however, where the National Assembly is dominated by a political party that differs to the president's own political leaning - for example, if a Socialist president coincides with a Republican government. This can "reduce the president to a ceremonial role", says Sky News.

This is a risk for both Le Pen and Macron, who are not affiliated to France's main political parties. According to CNBC, the winning candidate will need support from across the political spectrum in order to secure a parliamentary majority, making a coalition government more likely.

Elections for the National Assembly are scheduled for 11 and 18 June.

A route to diplomacy or a drawn-out process?

The two-round voting system is not unique to France - nor its former colonies. It is the system of choice for several European countries, including Finland, Poland and Portugal.

According to the Electoral Reform Society, voters tend to "vote with their heart" in the first round, reserving pragmatism for the second ballot. Having a final run-off also eliminates the problem of vote-splitting, where votes are divided between the most popular candidates, allowing a less popular one to seize victory

Elections web portal ACE argues that a two-round system can create goodwill between the running candidates. Those in the final run-off will benefit from the backing of the unsuccessful candidates, forcing "diverse interests to coalesce", it says. This is particularly noticeable in this year's race, with both Republican Francois Fillon and Benoit Hamon of the Socialists using their concession speeches to throw their support behind Macron.

Critics, however, claim the two-round voting system is unrepresentative. If a candidate does not make it through to the run-off, their votes are effectively wasted, which can make voters' voices unheard. Many regard the recent Paris protests as an example of the disillusionment this can cause. The Daily Telegraph reports that one banner read: "Neither plague nor cholera" in response to Sunday's choice of candidates.

Having two votes instead of one is also a costly and burdensome process, and not just for the administrators. Voters can suffer from election fatigue, leading to less engagement in the final round, says ACE.