Teens in crisis

American adolescents are suffering an epidemic of anxiety and depression. Why?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

American adolescents are suffering an epidemic of anxiety and depression. Why? Here's everything you need to know:

What's happening to kids?

Every available marker shows that over the past decade rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide have surged among children and teens in the U.S. The pandemic clearly made the problem worse — but the problem predates COVID, and it is consistent across regional and demographic lines. From 2009 to 2017, depression spiked 69 percent among 16 to 17-year-olds, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. From 2009 to 2021, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study, the share of high school students feeling "persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness" rose from 26 percent to 44 percent — the highest level ever recorded. Younger people are afflicted as well: Suicide is now the second leading cause of death for children 10 to 14, according to the CDC. The American Academy of Pediatrics says there are "dramatic increases" in hospital visits for mental health emergencies for the young, and declared this surge "a national emergency."

What's driving the crisis?

There appears to be a confluence of factors, but many social and child psychologists believe smartphones and social media play a central role. The circumstantial evidence there is undeniable: The "crisis emerged in the exact years when American teens were getting smartphones and becoming daily users of social media," social psychologist Jonathan Haidt told a Senate subcommittee in May. Over the past decade, he said, online life "transformed childhood activity, attention, social relationships, and consciousness." Social media can be damaging because it continually presents young people with images of others who seem more confident, successful, and attractive — making them feel inadequate and left out. They're "bombarded with messages…that erode their sense of self-worth," U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy wrote in a 2021 report. Facebook's internal research showed that a third of teen girls said Instagram "made them feel worse." Teens who spend five hours or more a day online are twice as likely to report unhappiness as those who spend less than an hour, according to Jean Twenge, a psychologist and the author of iGen. Another problem is that the internet presents teens struggling to form a sense of self with a staggering number of different possible identities. Finally, when kids spend so much time online, they also lose face-to-face connections with friends, mentors, and other adults.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why does that matter?

Interacting mostly by texts or social media lacks a warm human dimension that leaves many teens feeling lonely. "Teens are primed for social connection," said Joseph Allen, a clinical psychologist who specializes in adolescent social development. Social media, he said, "doesn't give them what they need." Kids who spend long hours online spend less time outside, playing sports, exercising, and attending religious services or other community activities — all of which help boost their mood. And with their phones (and video games) beckoning them 24/7 with features engineered to be addictive, teens are sleeping less. There's a mountain of evidence linking poor sleep to mental health issues, and today's adolescents are sleeping less than ever: The average high schooler now gets six and a half hours instead of the nine optimal for their age — leaving a generation with severe, chronic sleep deprivation. Research shows that a lack of sleep triggers the reactive and negative emotional centers of the brain. Some experts, however, are wary of pinning all the blame on phones and social media, and point to factors beyond the internet, including modern parenting styles.

How has parenting changed?

Psychologists warn that "helicopter parenting," with moms and dads hovering over every aspect of their kids' lives, impedes kids' ability to gain autonomy and develop confidence. In "accommodative" parenting, moms and dads try to eliminate sources of stress for their kids, who as a result don't learn how to deal with adversity and develop persistence. Research has also found that the pervasiveness of ominous news about climate change, partisan rancor, and the economy from various media sources leaves kids deeply pessimistic about the future. In a youth survey published last year in The Lancet, nearly half of respondents said worries about the fate of the planet interfered with their sleep and ability to enjoy themselves.

What can be done?

There is widespread agreement that pediatricians, parents, teachers, and schools need to put greater emphasis on detecting kids' emotional and mental health issues and providing help when they get in trouble. Last year 38 states enacted laws designed to improve school mental health resources, prevent suicides, and promote mental wellness among young people, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy. In October, the Biden administration announced more than $300 million in funding for youth mental health services, some of it aimed at addressing a dearth of trained mental-health professionals. Advocates call for expanded research into why so many teens are struggling. "We need to figure it out," said Candice Odgers, a psychologist at the University of California, Irvine, "because it's life-or-death for these kids."

A wide gender gap

The teen mental health crisis affects both genders — but not equally. More girls are suffering than boys, the data consistently show. Between 2019 and 2021, emergency room visits for suicide attempts rose 51 percent for teen girls and 4 percent for boys. Some experts believe a key reason for the divide is social media, which girls consume more of and respond to differently. Girls are more inclined to be self-conscious about their appearance and highly attuned to their place in the social pecking order. They're "more likely to engage in comparisons and to be affected by interpersonal feedback," said Mitchell Prinstein, chief science officer of the American Psychological Association. "Now those processes are hugely amplified with social media." A related issue is earlier onset of puberty, which heightens awareness of social messaging — and is significantly more pronounced in girls. "They are experiencing increased stress before their brains are wired up to handle it," said Donna Jackson Nakazawa, author of Girls on the Brink. It's "an evolutionary mismatch."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without people

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without peoplethe week recommends Solitude is different from loneliness

-

More women are using more testosterone despite limited research

More women are using more testosterone despite limited researchThe explainer There is no FDA-approved testosterone product for women

-

Climate change is getting under our skin

Climate change is getting under our skinUnder the radar Skin conditions are worsening because of warming temperatures

-

Food may contribute more to obesity than exercise

Food may contribute more to obesity than exerciseUnder the radar The devil's in the diet

-

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?Under the radar Catching diseases, not those ever-essential Zzs

-

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancer

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancerUnder the radar A once fearsome curse could be a blessing

-

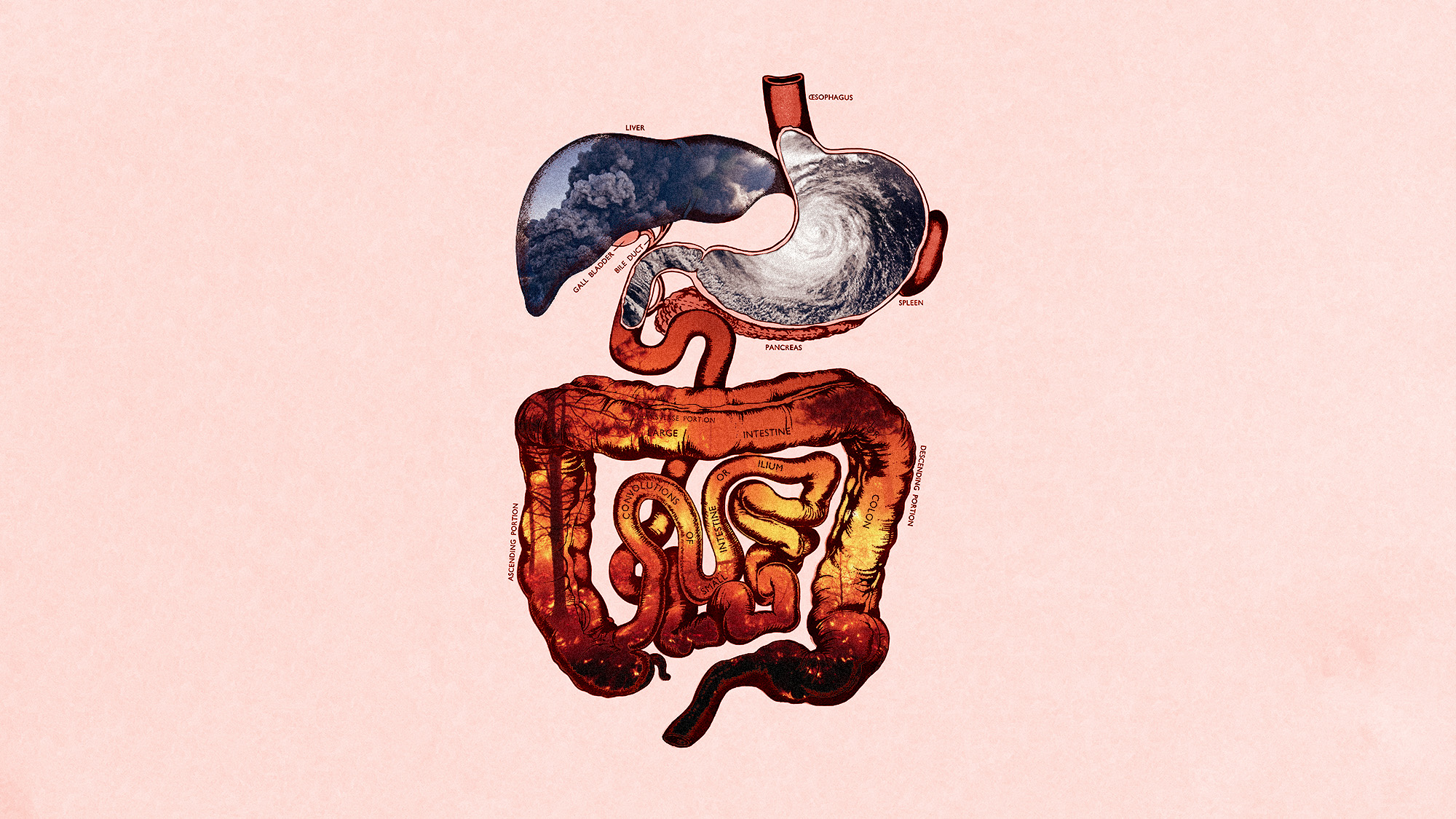

Climate change can impact our gut health

Climate change can impact our gut healthUnder the radar The gastrointestinal system is being gutted